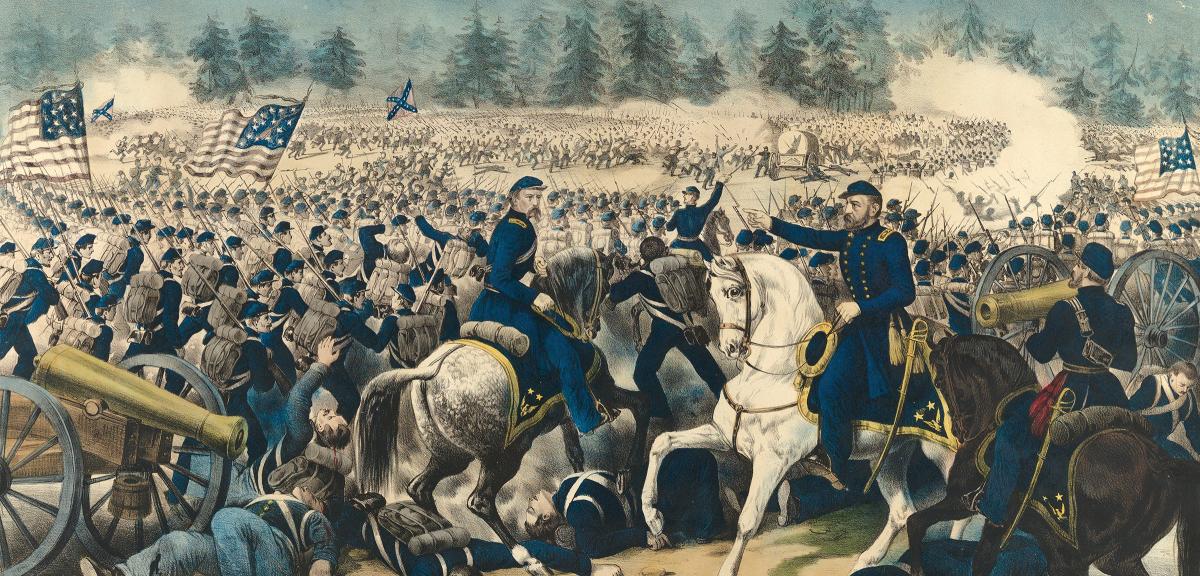

No, you are not imagining things. Gettysburg was indeed a landlocked battle, and there were no naval actions during the epic Civil War clash of 1–3 July 1863. But as a Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg National Military Park, I am always seeking connections to the battle that might be of special interest to visitors. The U.S. Navy’s ties to America’s Waterloo may not be readily apparent—yet they are there. What follows is a brief review of just a few of the many fascinating Navy-Gettysburg connections.

Brothers in Arms

Many do not realize that Navy Civil War hero Commander William Barker Cushing was the brother of one of the Battle of Gettysburg’s most famous yet tragic heroes, Army Lieutenant Alonzo Hereford Cushing. Each made a name for himself during the war—but sadly, one died doing so.

Alonzo Cushing earned the respect of superior officers and peers through the first two years of the Civil War. In command of Battery A, 4th U.S. Artillery, 22-year-old Cushing relished any opportunity to prove himself in combat. He would get his chance at Gettysburg.

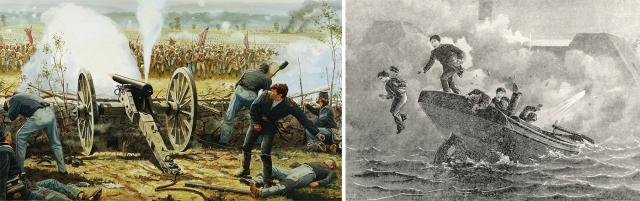

During the climactic third day of the battle, Cushing led his battery of U.S. Regulars during their heroic actions in defense of the center of the Union line during Pickett’s Charge. Finding themselves in a virtual maelstrom, casualties among the officers and men of Battery A quickly accumulated. Cushing himself was wounded by shell fragments twice during this action, once in the shoulder and once in the groin. Cushing’s men begged him to leave the field. In terrific pain and barely able to stand, Cushing protested, “No, I stay right here and fight it out, or die in the attempt.” Moments later, as he ordered one of his men to hold him up so he could continue to bark orders, he was killed instantly when an enemy bullet entered his mouth.

Young Cushing had been 5 feet, 9 inches tall, weighed barely 170 pounds, and had what many would call a “baby face.” Yet, reflecting on his heroism, one of his men said of him, “He looked more like a school girl than a warrior, but he was the best fighting man I ever saw.” Cushing was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2014 (151 years after the battle) for his heroic actions and bravery on 3 July 1863.

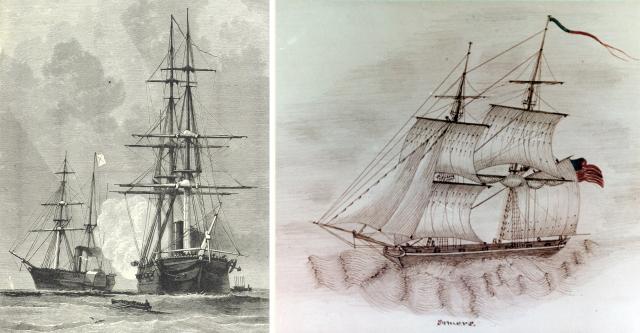

William Cushing, meanwhile, led many dangerous naval actions throughout the Civil War, but his most remarkable action, and that for which he is best known, came while leading a small-unit attack on the Confederate ironclad CSS Albemarle in October 1864. In this action, while under heavy enemy fire, Cushing and his crew rammed the Albemarle and detonated a torpedo-tipped spar (mine) underneath the hull. The result was a gaping hole in the bottom of the vessel that led directly to her demise. Cushing also gained plaudits for his heroic actions in the 1864–65 attacks on Fort Fisher, North Carolina, including marking the channel while under fire and leading a contingent of sailors and Marines in the final assault on the fort.

For his heroism, Cushing received the official Thanks of Congress, as recommended by President Abraham Lincoln, and a promotion to lieutenant commander. Of the 14 naval officers to be awarded the Thanks of Congress during the war, Cushing was the only non-flag officer. By war’s end, in addition to the Thanks of Congress, he had earned four commendations from the Navy Department. The Union’s wartime Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, once indicated that another great Navy hero, Admiral David Glasgow Farragut, had commented to him that “Cushing was the Hero of the War.”

Today, Cushing is honored at the U.S. Naval Academy with a portrait that hangs in Memorial Hall (within Bancroft Hall), directly above a plaque that pays tribute to all Academy graduates who have been awarded the Medal of Honor. The Navy has named five ships in his honor.

Father and Son

Navy Lieutenant Samuel Dana Greene was the son of Brigadier General George Sears Greene. General Greene’s heroic actions saved the Union Army’s right flank at Gettysburg, and Lieutenant Greene took command during one of the most famous battles in naval history. (The Greenes, incidentally, carried the legacy of a celebrated forebear—the Revolutionary War hero Major General Nathanael Greene.)

George Sears Greene led one of the most pivotal actions of the entire Battle of Gettysburg. During the late evening hours of 2 July, on the Union Army’s right flank at Culp’s Hill, Greene’s brigade almost singlehandedly held off an enemy force that outnumbered them by more than three to one. General Greene, affectionately referred to as “Pop” by his men, played a key role in this victory as he provided inspirational leadership throughout the desperate fight. But it was his actions before the fight that may have made the most difference.

Against the counsel of his division commander, Greene allowed his men to build protective walls of wood, dirt, and rock before any fighting began, so that if and when an attack came, his men could fight from behind what was better known as “breastworks.” Greene knew the old ways of fighting had become antiquated because of recent advances in the accuracy of weaponry. And as fate would have it, the breastworks proved to be the difference-maker for Greene’s brigade.

Fighting behind the breastworks, Greene’s boys, and a few additional regiments that assisted them, saved Culp’s Hill on the night of 2 July. Reflecting on the Union Army’s victory on Culp’s hill, Greene’s Corps commander, Major General Henry W. Slocum, put it best when he said, “The failure of the enemy to gain entire possession of our works was due entirely to the skill of General Greene and the heroic valor of his troops.”

The general’s Navy-lieutenant son likewise proved his mettle. Samuel Dana Greene was executive officer on board the USS Monitor during her historic 9 March 1862 clash with the CSS Virginia in history’s first duel between ironclads. During the course of the battle, Greene took command of the Monitor when the ship’s commanding officer, Lieutenant (later Rear Admiral) John L. Worden, was seriously wounded. As acting commander of the Monitor, Greene succeeded in protecting the USS Minnesota from the wrath of the Virginia.

Critics, however, felt Greene withdrew from pursuit of the Confederate ironclad too soon. Worden remained silent on the matter until 1868, when, in a letter to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, he attempted to bring some balance to the assessment of Greene’s performance. But by that time the damage to Greene’s reputation had been done. He had continued to serve as the Monitor’s executive officer until the ship met an untimely end, foundering in heavy seas while under tow and sinking on New Year’s Eve 1862. Greene survived the harrowing experience and went on to serve in blockading duty and pursuit of Confederate commerce raiders for the remainder of the Civil War.

After the war, Greene served nearly 20 more years with the Navy, during which he not only served at sea, in command of a number of vessels, but also as an instructor, department head, and in numerous positions of high responsibility at the Naval Academy. Yet, despite his distinguished career, Greene continued to struggle with the lack of proper recognition and affirmation for his performance as acting commander of the Monitor during her battle with the Virginia. Apparently, Greene revisited these self-doubts as he prepared an account of the battle for Century Magazine. And though it is only conjecture made by journalists and historians, numerous accounts indicate that these misgivings may have contributed to his suicide on 11 December 1884.

The Mackenzie Connections

Army Lieutenant Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, one of the greatest yet least-known soldiers in the nation’s history, was described by General Ulysses S. Grant as the Army’s “most promising young officer.” Mackenzie served as an engineer on the staff of Major General G. K. Warren, chief engineer of the Army of the Potomac, at Gettysburg. In this capacity he distinguished himself, especially in assisting Warren as he sought forces to defend the Union Army’s left flank on Little Round Top at a critical juncture of the battle.

Having graduated first in his class from West Point in 1862, Mackenzie fulfilled the promise of this lofty status as he achieved much success and recognition during the war. By its end, he was breveted (honorary rank) major general of volunteers and brigadier general in the regular Army. Mackenzie went on to gain renown as an Indian fighter in the Army’s late 19th-century frontier wars.

Mackenzie had multiple connections to the U.S. Navy—including two of the most sensational historic events to impact the Navy during the 1800s. The first came through Mackenzie’s father, Alexander Slidell Mackenzie. In 1842, while in command of a crew of trainees on board the USS Somers, Mackenzie found himself with a mutiny on his hands. The trainees he executed as a result of the mutiny included the Secretary of War’s son, Phillip Spencer, and acrimonious recriminations ensued. The Somers Incident, as it came to be known, was one of the major contributing factors in spurring Navy officials to establish a land-based school at Annapolis for training its midshipmen.

The second connection between Ranald Mackenzie and the U.S. Navy centered on his uncle, John Slidell, one of two Confederate diplomats (he was Confederate Commissioner to France) to be captured by the U.S. Navy while on board the British ship RMS Trent, bound for France. This act, which came to be known as the Trent Affair, raised tensions between the United States and Great Britain. The last thing the United States needed, while in the midst of the Civil War, was a conflict with Great Britain. So to appease the British, Slidell and his compatriot were released.

In yet another noteworthy connection to the U.S. Navy, Ranald Mackenzie’s aunt married Matthew C. Perry, brother of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry. Mackenzie also had two brothers who served as officers in the U.S. Navy.

Gettysburg and Old Ironsides

The stellar leadership of Major General Andrew Atkinson Humphreys proved invaluable to the Union Army at Gettysburg. Prior to the commencement of hostilities on day two of the three-day battle, Humphreys’ division was ordered by its corps commander, Major General Daniel E. Sickles, to a position near the Emmitsburg Road. It placed Humphreys and his men way in advance of the prescribed “fishhook” position put forth by Major General George G. Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac. As such, Humphreys’ division was left in an extremely vulnerable and isolated position, with its right flank “in the air.” Humphreys’ men would pay dearly for Sickles’ ill-fated decision.

As the Confederate assault began late in the afternoon of 2 July, Humphreys’ men soon found themselves hard-pressed on all fronts. Threatened on their left by a portion of General William Barksdale’s brigade and on their front and right flank by two additional Confederate brigades, Humphreys’ division was nearly surrounded. Though Humphreys was convinced his men could hold their own, he soon received orders to fall back. And though most battlefield heroes find their fame in leading heroic attacks, Humphreys would find his in the manner by which he skillfully managed the deliberate retreat of his division. Demonstrating an unsurpassed coolness under fire, his leadership during this organized withdrawal proved to be one of the keys to the salvation of Meade’s fishhook line, as it bought precious time for reinforcements to arrive to stop the Confederates’ near-breakthrough.

Humphreys’ grandfather, Joshua Humphreys, was one of the most respected naval architects in the United States during the late 18th century, a man known to many as the “Father of the U.S. Navy.” When the government passed the Navy Act of 1794 (also known as the “Frigates Bill”), which called for the establishment of a U.S. fleet of six frigates, several well-known shipwrights vied for the honor of having their designs selected for these to-be-built vessels. But it was Humphreys’ unique design for large, strong, and nimble frigates that was chosen by Secretary of War Henry Knox as the preferred design. And in conjunction with the selection of his ship design, Humphreys also was appointed “Master Constructor of the United States,” thus being placed in overall command of the building of the Navy’s first frigates. Years later, his son Samuel, General Andrew Humphreys’ father, also would serve in the role of Master Constructor.

The vessels envisioned by Humphreys served the nation well in the Quasi-War with France and the Barbary Wars. But Humphreys’ frigates, especially the USS Constitution, gained their greatest fame during the War of 1812. For more than 200 years Humphreys’ design has proven its worth. The Constitution, “Old Ironsides,” is the oldest active U.S. Navy vessel in commission (interestingly, she is also the only U.S. vessel currently in commission that can claim the distinction of having sunk an enemy vessel in action).

Lockwood: The Army-Navy Man

Brigadier General Henry Hayes Lockwood, who led an inexperienced infantry brigade into its baptism of fire during the Battle of Gettysburg, also was one of the co-builders and founding instructors of the U.S. Naval Academy. With the onset of the Civil War, Professor Lockwood returned to his Army roots—he had graduated from West Point in 1836 and served in the Seminole wars. This time, he re-entered the fray as a member of the Volunteers. Initially serving as colonel of the 1st Delaware Infantry Regiment, he soon was promoted to brigadier general. In November 1861, Lockwood led a bloodless campaign against Confederate forces occupying Virginia’s three counties located on the Delmarva Peninsula.

As General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began its invasion of the North in the summer of 1863, troops under Lockwood’s charge were called to action. Attached to the Army of the Potomac’s XII Corps, Lockwood’s Independent Brigade (1st Maryland Potomac Home Brigade, 1st Maryland Eastern Shore, and 150th New York) served on both flanks of Meade’s famous fishhook-shaped line of defense at Gettysburg.

The brigade’s most noteworthy accomplishments during the battle came in assisting with the repulse of Barksdale’s Brigade’s penetration of General Sickles’ III Corps line on the afternoon of 2 July, and in providing able assistance in holding off the Confederate assaults on Culp’s Hill on the morning of 3 July. During these actions, Lockwood earned the lasting admiration and respect of his men, as he was always found leading his troops into action from the front of the line of battle.

At war’s end, Lockwood returned to the Naval Academy and eventually concluded his career at the Naval Observatory. He retired in 1876, having served his nation for nearly 40 years, 35 with the Navy and five with the Army, including four during the Civil War.

Bancroft’s Gettysburg Address and Other Links

The USS Gettysburg (CG-64), Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN-69), and Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) all have ties to Gettysburg, and each has sent officers and crew to Gettysburg to volunteer in battlefield restoration. The current USS Gettysburg is the third ship the U.S. Navy has named in honor of the battle. In 2014, the Gettysburg wardroom was renamed in honor of Lieutenant Alonzo Cushing, Gettysburg hero and Medal of Honor recipient. The USS Abraham Lincoln can be connected to Gettysburg through President Lincoln and the famous speech he delivered at the dedication of Gettysburg National Cemetery. The USS Dwight D. Eisenhower also can be linked to Gettysburg through its presidential namesake. “Ike” purchased a home adjacent to the battlefield in 1950, and after completion of his second presidential term, he retired to his Gettysburg home. The Gettysburg Municipal Building and the Gettysburg Library feature conference rooms that are dedicated to the USS Gettysburg and Dwight D. Eisenhower, respectively.

One of the most remarkable monuments on the battlefield at Gettysburg is the Eternal Peace Light Memorial. Designed by the famous architect Paul Philippe Cret, the “Peace Light” pays tribute to the everlasting peace between the North and South through an eternal flame that burns 24 hours a day. Cret’s artistry also adorns the Naval Academy, where he designed an addition to the iconic Naval Academy Chapel that more than doubled its capacity.

The Maryland monument at Gettysburg, dedicated in 1994, was created by the hand of noted sculptor Lawrence M. Ludke. Ludke’s works also grace the grounds of the Naval Academy. His sculptures there pay tribute to two of the Navy’s greatest modern-day heroes: Vice Admiral William P. Lawrence and Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale.

There are these sundry Navy-Gettysburg connections, and there are more. But perhaps the most mystical one is this: Secretary of the Navy and U.S. Naval Academy founder George Bancroft received one of the five known autographed copies of President Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address—thereby eternally linking the U.S. Navy to Gettysburg, President Lincoln, and one of the most famous speeches in world history.

Sources:

Nancy Prothro Arbuthnot, Guiding Lights: United States Naval Academy Monuments and Memorials (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2009).

Mark M. Boatner III, The Civil War Dictionary, rev. ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1991).

John W. Busey and David G. Martin, Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg (Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 1982).

John D. Cox, Culp’s Hill: The Attack and Defense of the Union Flank, July 2, 1863 (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2003).

James Tertius deKay, Monitor: The Story of the Legendary Civil War Ironclad and the Man Whose Invention Changed the Course of History (New York: Walker Publishing Company, 1997).

Allen Johnson, Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Scribner’s, 1958).

Shelby Foote, The Civil War: A Narrative—Red River to Appomattox (New York: Random House, 1974).

Thomas C. Gillmer, Old Ironsides: The Rise, Decline, and Resurrection of the USS Constitution (Camden, ME: International Maritime, 1993).

S. Dana Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 1 (Edison, NJ: Castle, 1982 reprint of 1887 original), 719–29.

Frederick W. Hawthorne, Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments (Hanover, PA: Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides and Sheridan Press, 1988).

A. A. Hoehling, Thunder at Hampton Roads: The U.S.S. Monitor—Its Battle with the Merrimack and Its Recent Discovery (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1976).

Taylor Baldwin Kiland and Jamie Howren, A Walk in the Yard: A Self-Guided Tour of the U.S. Naval Academy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007).

Martha C. King, Chaplain C. Richard Duncan, VADM Ted Parker, USN (Ret.), and Joel Pautsch, United States Naval Academy Chapel, Annapolis, Maryland (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Academy Alumni Association, 2014).

Kevin Knodell and Kelly Swan, “Acts of Valor: Lewis C. Shepard, U.S. Navy,” Naval History 33, no. 1 (February 2019): 54–57.

Richard G. Latture, “On Our Scope,” Naval History 21, no. 2 (April 2007): 4.

Diana Loski, “George Greene: The Union’s Right Hand Man,” The Gettysburg Experience, June 2014.

Diana Loski, “Ike and Gettysburg” The Gettysburg Experience, October 2013.

Southern Historical Collection, Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina.

Jamie Malanowski, Commander Will Cushing: Daredevil Hero of the Civil War (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014).

Lloyd J. Matthews, General Henry Lockwood of Delaware (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2014).

Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, “Commander Samuel Dana Greene, USN."

Eric Mills, Chesapeake Bay in the Civil War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2010).

Kyle Mizokami, “The Only Ship Left in America’s Fleet That Actually Sunk an Enemy Ship Is 200 Years Old,” Popular Mechanics, 6 October 2015.

National Park Service, “Lt. Alonzo Cushing at Gettysburg.”

New York Monuments Commission, In Memoriam: George Sears Greene, Brevet Major General, United States Volunteers, 1801–1899 (Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company, 1909).

Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993).

Harry W. Pfanz, The Battle of Gettysburg (Fort Washington, PA: Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1994).

Harry W. Pfanz, Gettysburg: The Second Day (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987).

Edmund J. Raus Jr., A Generation on the March: The Union Army at Gettysburg (Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1996).

Robert J. Schneller Jr., Cushing: Civil War SEAL (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2004).

Jack Sweetman and Thomas J. Cutler, The U.S. Naval Academy: An Illustrated History, rev. ed. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995).

Texas State Historical Association, “Mackenzie, Ranald Slidell.”

Ian W. Toll, Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006).

Daniel Carroll Toomey, Marylanders at Gettysburg (Baltimore, MD: Toomey Press, 1994).

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, “Andrew Atkinson Humphreys.”

Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders (Baton Rouge: LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1992).