In the Navy, the term “rope” refers to both fiber and wire. Fiber ropes can be natural or synthetic, the former made of natural materials such as manila or hemp, and the latter made of man-made materials such as nylon or polyester. Wire rope generally is stronger than fiber, but it is less flexible and can be difficult to handle.

The art of working with line or rope is called marlinespike seamanship, named for a handheld, spike-like tool used in working with wire rope, called a marlinespike. A similar tool used with fiber is called a fid.

Like in so many nautical topics, the terms used in marlinespike seamanship can be tricky. While there are certain “rules” of terminology, they sometimes overlap and are not absolute.

Fiber rope (both natural and synthetic) is usually called rope, but only as long as it is still in its original coil. Once a piece has been cut to be used for some purpose (such as mooring or heaving), it is then called a line. Rope made of wire (or a combination of wire and fiber) is usually called wire rope or simply wire, even if it has been cut from its original coil and is being used for a specific purpose.

What many would call a loop in a line is called a bight in the Navy. Looping a line around an object is called taking a turn or taking a round turn. A permanent loop fixed onto the end of a line is called an eye. Lines do not “break” in the Navy, they part. The free end of a length of line is called the bitter end.

To a sailor, a knot in a line usually means the line is tied to itself. When two lines are tied together, they form a bend. When a piece of line is tied to some other object, it is called a hitch. One guiding principle is that knots are usually meant to be permanent and are therefore more difficult to untie than are bends and hitches.

When two lines are to be joined end to end in such a way as to merge them into one, they are spliced. A splice between two lines will run through, or over, another object more easily than a knot.

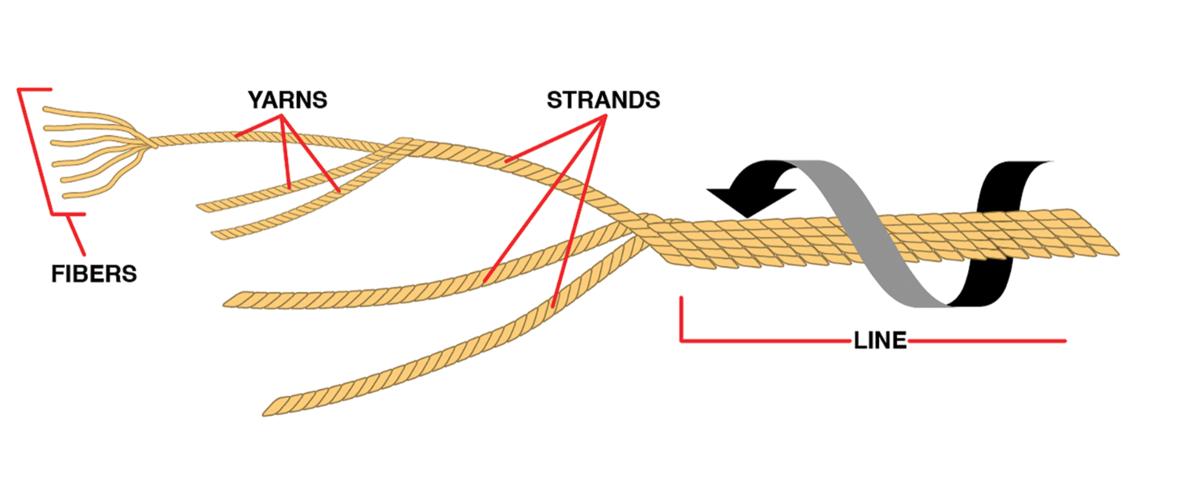

Construction of a rope often starts with small fibers, which are twisted until they form larger pieces called yarns. Then the yarns are twisted in the opposite direction to form strands, after which they are twisted in the original direction to become a line. The direction of this final twisting determines the lay of the line. This is important because lines should always be coiled in the direction of their lay. For example, right-laid line should always be coiled in right-hand (clockwise) turns, which prevents kinking and extends the life of the line.

Lines can also be formed by a different process called braiding. Braided lines have certain advantages over twisted ones. They will not kink and will not flex open to admit dirt or abrasives. The construction of some braids, however, makes it impossible to inspect the inner yarns for damage.

Wire rope consists of individual wires made of steel or other metal, in various sizes, laid together to form strands. The number of wires in a strand varies according to the purpose for which the rope is intended. A large number of small wires is flexible, but small wires break more easily, allowing the rope to be damaged by external abrasion. When made of a smaller number of larger wires, the wire rope is more resistant to abrasion but less flexible.

Natural- and synthetic-fiber lines each have advantages and disadvantages. The common synthetic fibers—nylon, polyester (Dacron), polypropylene, and polyethylene (in descending order of strength)—generally are stronger than natural fibers and are not subject to rot. Nylon is more than twice as strong as manila, the most common natural fiber; it lasts five times as long and will stand seven times the shock load. Dacron gets stronger when wet, and polypropylene is so light it floats, advantageous in a marine environment. The biggest disadvantages of synthetic lines are that they do not hold knots as well as natural fibers and they stretch under heavy loads, making it difficult to tell when they are going to part.

Sailors who work with natural-fiber line soon learn how to judge tension by the sound the line makes. Unfortunately, although synthetic line under heavy strain thins considerably, it gives no audible indication of stress—even when it is about to part. For this reason, sailors often attach a tattletale line to synthetic line when it is subjected to loads that may exceed its safe working load. A tattletale is a piece of smaller natural-fiber line that is attached to a synthetic line at two carefully measured points so that it droops down when the line is not under strain. As the synthetic line stretches, the droop in the tattletale will get less and less, until the tattletale becomes taut and is lying parallel to the synthetic line, warning that the line is in danger of parting.

In this age of high technology, it is both amazing and somehow reassuring that methods and materials are still in use from the earliest days, when sailors first went “down to the sea in ships.”