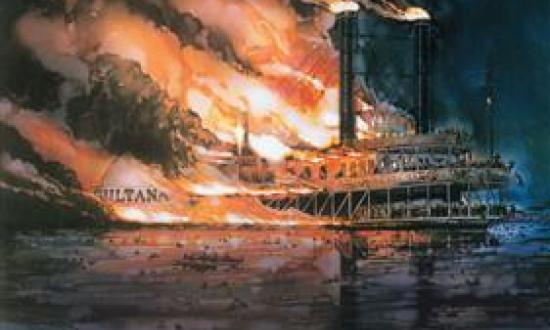

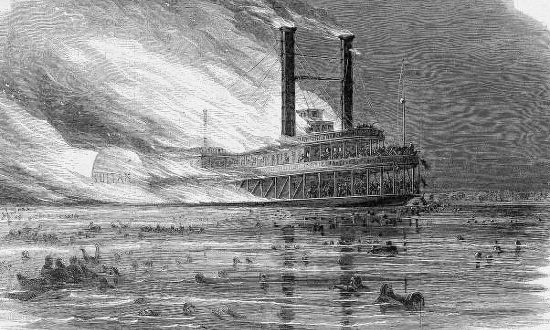

In his book recently published by the Naval Institute Press, Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana: The Worst Maritime Disaster in American History, author Gene Eric Salecker sheds new light on the Sultana’s tragic fate. She was a sidewheel Mississippi steamboat carrying nearly 2,000 released Union prisoners-of-war back north at the end of the Civil War. At 0200 on 27 April 1865, when the boat was seven miles above Memphis, her boilers exploded. Almost 1,200 people perished.

Salecker, historical consultant for the Sultana Disaster Museum in Marion, Arkansas, recently participated in an author q&a with former Naval History editor-in-chief Fred Schultz to discuss the book:

FS: After having read your exhaustive story of the various iterations of the steamboat Sultana, I couldn’t help but compare her fate to the loss of the Titanic, which, as I’m sure you know, has received much more attention from historians. What is the allure to your treatment of the Sultana stories? Why should potential readers care?

GES: Readers should care about the Sultana since it was the greatest maritime disaster in American history. It happened near Memphis, Tennessee, almost in the very heart of the United States, and yet very few people have ever heard about it. While the Titanic caused more deaths, the great ocean liner was a British vessel and carried people from several different countries. On the other hand, the Sultana was an American steamboat carrying almost 100 percent American passengers, including almost 2,000 recently released Union prisoners-of-war returning home to their families.

The Sultana should be remembered because what happened to her need not have happened. Through the corruption of Captain Reuben Hatch, a Union officer at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the captain of the Sultana, James Cass Mason, those 2,000 ex-prisoners were crowded onto a boat with a legal carrying capacity of only 376 passengers. Since the US government was paying steamboat captains a dividend to carry the prisoners back north, Captain Hatch and the captain of the Sultana worked out a deal whereby Hatch would guarantee a large load of ex-prisoners for the Sultana in exchange for a kickback of the government funds from Captain Mason. What the reader needs to know is that Captain Hatch, who had been corrupt throughout the war, would not have been there if not for some influential friends and relatives in the government, including President Abraham Lincoln.

The Sultana story is one of greed and corruption, as well as pathos and sadness. A potential reader should care about this story because it shows that greed and corruption in the government is not a new thing. It has been going on for centuries.

FS: Tell us why the Sultana Disaster Museum is located in Marion, Arkansas. What is the connection?

GES: The Sultana Disaster Museum is located in Marion because that is the closest city to the remains of the vessel. The Sultana sank in the Mississippi River near Marion, and over the years, the wreck was eventually covered with silt. In the early 1900s, the Mississippi River shifted about two miles to the east, leaving the wreck under about 15 feet of Arkansas soil. The city of Marion is the closest city to the wreck site and is also the home to a number of descendants of people who aided in the rescue of the Sultana victims.

FS: What was the role played by the last Sultana in the Civil War, and how significant was that role?

GES: Sultana (No. 5) was built in February 1863, but she was used extensively throughout the last two years of the Civil War to carry Union troops and supplies on the Cumberland and the Mississippi Rivers to aid in the collapse of the Confederacy. The Sultana was especially helpful to the Union forces under General Ulysses S. Grant as he moved to capture Vicksburg, Mississippi, and open the Mississippi River to Union navigation. After the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, Louisiana, in July 1863 and the opening of the Mississippi, the Sultana was used to bring cotton from parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas that were now under Union control up north so that it could be sent to Eastern manufacturers that had been starving for the raw material. And finally, at the end of the war, the Sultana would have played a significant role in transporting former Union prisoners-of-war back to the North. However, the explosion of her boilers just above Memphis on 27 April 1865 put a terrible end to that endeavor.

FS: In the course of your story, you declare that “It is now possible to write a work of historical nonfiction without ever leaving home.” How do you actually feel about that? Is it a good thing? Or does it let would-be historians off the hook from paying their own dues for embarking on the composition of a piece of nonfiction?

GES: I am a bit ambivalent about that. In writing my first few books I literally had to go to the U.S., state, and military archives to do my research. I copied everything I could find, even though I may never use the material. It was easier to copy everything and not use some of it than to forget to copy something and need it later on. That meant another expensive trip and more time.

Now, through the use of the internet, people can search hundred, perhaps thousands, of newspapers, from the United States as well as from around the world. They can search material held in small, local historical societies. More and more government documents are coming online every day, so it is now quick and easy to make a search for needed information.

As to whether it is a good thing or not, yes, I believe that it is a good thing to do so much research and get so much information from the internet. However, as I said, a person still needs to go to a resource location such as a museum archive to get the basic facts. The rest can be gotten through the internet, which can be a positive thing—if done correctly. I do not feel that it lets would-be historians off the hook as long as they go the extra mile and gather the basic facts, etc., through diligent leg work.

FS: It seems to this reader that one of the main reasons for such a series of disasters for vessels named Sultana is that the owners of the steamers and the people entrusted with actually navigating the ships [boats] were ignoring the fact that overcrowding may have been the principal reason for the long list of tragedies. The Sultana tragedies seem to be classic examples of putting profit over safety. How do you feel about that?

GES: I agree wholeheartedly. As shown in my book, when steam navigation of American waterways first began, there were very little, if any, laws for safety. Then, once some laws were passed, they were generally ignored. It seemed that profit was the driving factor for most steamboat owners and captains. Steamboats should not have been racing each other, but it happened all the time, and the public loved it! No one seemed to question the danger of a steamboat race until there was an accident or the boilers exploded.

As for the Sultana disaster itself, it was clearly a case of putting profit over safety. Although one of the Sultana’s boilers was being repaired when the ex-prisoners were being crowded aboard the boat, none of the Union officers seemed to mind. Although the patched boiler was not the cause of the disaster, it was certainly indicative that the Sultana had faulty boilers. Yet Captain Mason of the Sultana, and Captain Reuben Hatch, the chief quartermaster at Vicksburg, saw no problem in crowding as many men as possible on board the boat, hoping to reap the biggest profit possible.

Even after the Sultana disaster, steamboat captains continued to accept profit over safety, as shown by boats that exploded when crammed full of recent immigrants moving westward. It was not until the U.S. government began to crack down and either enact, or enforce, the laws, that safety became an overriding factor in steamboat travel.

FS: Your handling of how the owners and crews of these vessels seemed to have not factored in the reality that dirty river water was not suitable for being used to create steam, and thus propulsion.

GES: The dirty river water of the lower Mississippi was not really thought of as a problem by the steamboat captains or engineers. Although they knew that the water above Cairo was cleaner, the only problem they thought they faced by the dirtier lower Mississippi water was that they had to clean their boilers more often. And, in fact, when the boats used the regular flue boilers, the sediment in the water was not too much of a problem. The Sultana’s tubular boilers, however, were harder to clean and could form pockets of sediment that could insulate a section of the tubes from the surrounding water and lead to overheating of the tubes. Although sediment settled in the bottom of even the flue boilers, it was never thought to be much of a hazard.

FS: Which “cargo” would you say was more important and most profitable—the goods and materials or the obviously wealthy patrons who were there just for a glamorous boat ride?

GES: Goods and materials were by far the most important and more profitable “cargo” to carry. The cost for a stateroom fare was marginal when compared to the amount that could be gained by carrying freight and goods. While “wealthy patrons” might buy drinks all night at the bar, the bar was usually privately owned, with just a share of the profits going to the steamboat captain and/or owner. And, the cost of a stateroom was not based on the wealth of the traveler. It was a standard fare, no matter who you were.

Also, many people chose to pay for only deck passage, which restricted the traveler to the lowest (main) deck. He/she ate the same fare as the roustabouts and hands unless he/she bought a dinner ticket. Then the traveler could go upstairs and eat at the main tables with the first-class passengers. Freight and cargo were much more profitable—although the movement of animals could be a backbreaking, smelly proposition!

FS: In writing this book and having devoted much of your lifetime to telling the true stories of the vessels named Sultana, when did your aim to dispel myths and legends take over your outlook?

GES: I began to dispel the myths and untruths surrounding the Sultana shortly after the Naval Institute Press published my first book in 1996. I gave only short shrift to the coal-torpedo sabotage theory. Yet, shortly after my 1996 book came out, a cabal of people sprang up touting the sabotage theory once again. Whenever possible, I tried to dispel that myth. Then, as time went on, I noticed that the numbers of people supposedly on board the Sultana when she exploded, and the number of people that died on board the Sultana, kept going up and up and up. When was it going to stop and where were the numbers going to end?

In 2015, after I retired, I decided to look at all the known lists to discover who was actually on the Sultana and how many lived and died. While researching those numbers, I ran across other myths and legends that were incorrect or misleading, while at the same time verifying many of the stories. I then decided that since it had been 25 years since the publication of my first book, I needed to put out a new book on the Sultana. I had learned so much more, and collected so many more first-person accounts from the people on board, from the rescuers, and from the people involved, that I knew I had to write a new tell-all book that would dispel, as well as verify, all of the stories, rumors, and myths surrounding the disaster.

FS: Given the mistrust of any reporting from the press in some parts of our society today, how reliable would you say the reporting on these disasters was back in its day?

GES: I think the reporting of the Sultana disaster in April and May 1865 was pretty accurate. Many of the stories that the newspapers got from survivors were not always correct (one man said that there were people from every state in the Union on board—not so), but they were reporting what they were told. When steamboats went out to investigate the wreck, they reported on what was found. They tended to report what others thought these findings meant, but they very rarely added their own input, one way or another. I think reporting was much more accurate, and less political, than it is today.