In the weeks following the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy advanced like a “sea-air-land Blitzkrieg, as precisely choreographed as a ballet.”1 World War II historian Samuel Eliot Morison described the Japanese forces moving like

the insidious yet irresistible clutching of multiple tentacles. . . . Like some vast octopus, [the Japanese] relied on strangling many small points rather than concentrating on a vital organ. No one arm attempted to meet the entire strength of the ABDA Fleet.2

The Western democracies responded to the December 1941 attacks across the Pacific by forming the initial supreme allied American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM). The four nations announced the appointment of British General Sir Archibald Wavell and the command’s formation on 1 January 1942. ABDACOM collapsed within eight weeks. General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral Chester Nimitz eventually would win the war with myriad Allied forces under their commands.

ABDACOM’s failure to blunt Imperial Japan’s march through East Asia presents key lessons for hypothetical Sino-American and allied conflict. Today, just like 80 years ago, joint and international forces are forward deployed throughout the Indo-Pacific, maintaining national interests through presence. Today, as eight decades previously, rising aggressors threaten territorial encroachment throughout East Asia, operating with mass and speed in their near seas. ABDACOM may never have been able to completely arrest Japanese attacks throughout the Western Pacific, but it could have imposed greater costs and provided more time for allies to surge forces into the region, just as their war plans pre-supposed.

Modern coalitions must learn from ABDACOM to avoid a fait accompli over a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. While military training and readiness played roles in its failure, ABDACOM collapsed principally because of a lack of joint and combined unity of command. Despite the appearance of unity in the organizational chart and regular conferences, individual national incentives denuded the nascent alliance of its strength, leaving the Imperial Japanese forces to defeat ABDACOM in detail through early 1942. If the former Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Combatant Command (INDOPACOM) Admiral Phil Davidson is right, and the “threat [to Taiwan] is manifest . . . in the next [four] years,” the United States and its allies must establish an active American-British-Japanese-Australian (ABJA) Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) today.

Arcadia: Coalescing around a Coalition

Soon after Germany declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill arrived at the White House for the First Washington Conference, codenamed Arcadia. There he would discuss strategy with President Roosevelt, the Combined Chiefs of Staff, and their entourages.3 While defining exactly what a “Europe-first” strategy meant in practice, both nations received reports of Japanese captures of Hong Kong and Wake Island.4 Along with Australia, New Zealand, and the Dutch-in-exile, the remaining Allied islands needed a coherent plan for garrisons and to intercept Japanese advances.

On Christmas morning, 1941, Chief of Staff of the Army General George Marshall argued amongst the staffs, “I am convinced that there must be one man in command of the entire theater-air, ground, and ships. We cannot manage by cooperation . . . If we make a plan for unified command now, it will solve nine-tenths of our troubles.”5 Both sides agreed, but the prospect of Anglo-American unity in command challenged both nationalities and services. Marshall, like others, understood that military command in a coalition was inextricably linked with diplomacy and politics, requiring civilian leader concurrence to proceed.6

During a 26 December meeting, other U.S. officers were lukewarm to the unified command idea, but British service chiefs actively fought it and encouraged Churchill to speak against it. Choosing unity of command over national autonomy, Marshall maneuvered around British sentiment in concert with the President and advisor Harry Hopkins by nominating the British general, Field Marshal Sir Archibald P. Wavell as the first Supreme Allied Commander of ABDACOM. ABDACOM’s area of responsibility would include modern-day Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, northwestern Australia, the Philippines, and their outlying seas.7 Churchill, himself a navalist, counterproposed that U.S. Asiatic Fleet Commander, Admiral Thomas Hart, would be better suited in command of British and American ships in the Pacific theater.8 Admiral Ernest King, then Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and later Chief of Naval Operations (COMINCH-CNO) warmed to Marshall’s proposal and obstinately backed Wavell for ABDACOM.

Under the combined pressure of the U.S. service chiefs, the President, and his advisors, Churchill relented. Dutch and Australian leaders would assent to Wavell four days later. On learning of the ABDACOM plan, Chief of the [British] Imperial General Staff (CIGS) General Alan Brooke wrote in his diary, “The whole scheme [is] wild and half-baked and only catering for one area of action, namely western Pacific, one enemy, Japan, and no central control.”9 Wavell landed on the island of Batavia on 10 January 1942. Within 43 days he would be writing the U.S.-British Combined Service Chiefs recommending the dissolution of his command.10

Wanted: Unity of Effort

At the operational level, Commander, Asiatic Fleet, Admiral Thomas Hart recounts in his declassified “Narrative of Events,” that U.S. preparation for war “properly beg[a]n about mid-January 1941,” with initial conferences with British, Dutch, and Australian leaders.11 These conferences would continue throughout the year, yet Hart could not even agree with his Army counterparts in the Philippines on a unified plan for air forces employment.12 During a second conference with then-Commander, US Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), General Douglas MacArthur in early October 1941, Hart again requested aircraft cooperation and met with Dutch Army and British Royal Air Force representatives requesting the same.13 MacArthur pushed the issue off, pending an official letter penned by Hart with more specific proposals and a “concrete basis for further discussion.”14

On 27 October 1941, Hart relayed to the Navy Department that “no real progress had been made toward agreement on joint naval operations with the British and Dutch.”15 In coordination with a Royal Australian Navy representative during a 2–3 November meeting, Hart relayed his overall proposal for the war, but “the effort at entering into adequate arrangements for joint operations of army and navy aircraft, over the seas, [was] met with a decided rebuff from the USAFFE.”16 On 1 December 1941, MacArthur and Hart would agree on different sectors for joint airborne reconnaissance, thanks to the prior consultation between their staffs. The plan was short-lived.

Despite MacArthur's learning of the Pearl Harbor attack hours prior, Japanese air forces successfully attacked the Army Far East Air Force on the ground. Over half of the 181 airplanes at Clark Air Field in the Philippines were destroyed, with many others damaged. The resulting Japanese air superiority hampered Hart’s 29 submarines attempting to defend the Philippines both by a lack of allied scouting and the perceived threat that aircraft imposed on submarines, leading the latter to operate deeper and less effectively than their systems warranted. The U.S. Mk 14 torpedoes hindered the submarines that did attempt to engage Japanese expeditionary forces, because the weapons ran deeper than set depth and many failed to detonate on impact; results that became evident within weeks of the war’s start.17 Ashore, the 4th Marine Regiment had returned from China to the Philippines days before the war, and like the air forces before them, Hart and MacArthur lacked consensus on the employment of Marines beyond constabulary duty for Philippine naval bases.[18] On 23 December 1941, the 4th Marines would be shifted to USAFFE control, and fight to eventual surrender on Corregidor Island in May 1942.

On 2 January 1942, Hart received a dispatch stating that the allied fleets would soon be placed under a joint command.19 While the strategic leaders of Allied nations had sought to resolve unity of command at their level, balancing national interests with in-theater forces remained a challenge. Admiral Hart was given the command of naval forces, ABDAFLOAT, and his fellow ABDA staff struggled to align their interests within a multinational consensus. During meetings on 9–10 January 1942, Admiral Hart received endorsement from fellow U.S. Army Air Forces Lieutenant General George Brett and Major General Lewis Brereton on joint ship and aircraft cooperation, only to be immediately undercut by the operational focus.20

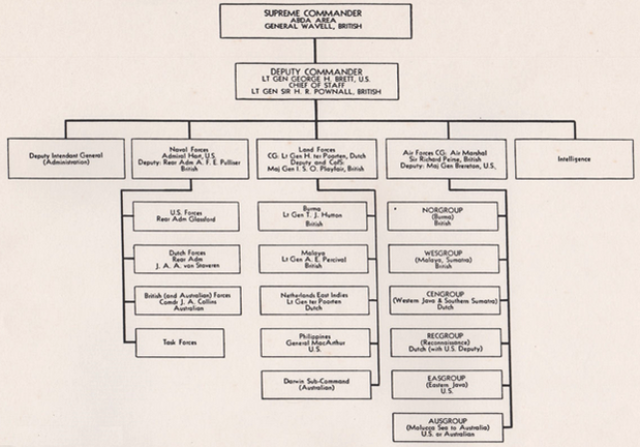

Hart complained in his report, “it was found that British naval interests . . . were entirely centered on guarding troop convoys [to] Singapore,” and Royal Navy Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton reinforced these desires, requesting that the British system for resupplying Singapore continue outside the joint naval command.21 Hart disagreed, as it “would mean responsibility without commensurate authority,” yet the following day General Wavell reiterated “that the two missions [surface navy striking forces and convoy protection] were of about equal importance, [and] that at least the convoy-escort task was not secondary.”22 Within a week of regular ABDA operations, Admiral Hart described the organization depicted in the chart above as a, “very complicated command” and that between the three fleet commanders “there was always an agreement in the end [on operations], but [it was] frequently preceded by efforts to ‘get the others to do it.’”23

Conflict over the operational focus persisted. At the end of January, President Roosevelt endorsed the priority resupply of the flailing General MacArthur on the Philippines, including the use of Hart’s submarines to deliver paltry amounts of ammunition.24 In a follow-on ABDA Commander’s conference, Hart “stated that Allied naval forces could have accomplished much more in the way of direct opposition to the enemy advance if no cruisers and destroyers had been used for escort duty. . . . Those statements were unwelcomed but true.”25 The U.S. Navy achieved tactical victory during a night raid on Japanese transports ships at Balikpapan, but strategic impact was fleeting. Singapore, the “Gibraltar of the East,” fell on 15 February, and with it, British aspirations to hold the “Malay Barrier” against further Japanese incursions. By that day, Admiral Hart had received and processed his turnover of the ABDAFLOAT operational command to Dutch Vice Admiral Conrad Helfrich.26 Having already been overrun by Nazis in Europe and reinforced by their 300-year presence in the East Indies, Helfrich and the Dutch committed to fighting. Helfrich directed Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman to assemble a Dutch, British, and American Combined Striking Force. The Japanese would complete ABDACOM’s annihilation by decisively defeating Doorman’s Strike Force at the 27 February Battle of the Java Sea, and subsequent smaller battles throughout the East Indies. While tactical heroism in the face of daunting odds was ever-present, ABDACOM failed. The coalition collapsed because it never agreed on a joint and combined strategy nor massed its forces until after the Japanese took the Netherlands East Indies. Future coalitions must avoid the same mistakes.

Wrangling Today’s Anglosphere and Japan’s Constitution

The modern ABJA Combined Joint Task Force will face similar military-diplomatic roadblocks to the ones of 1941, but the seeds of a strengthening alliance are growing. On 15 September 2021, the three primary Anglosphere governments announced the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) trilateral security pact. AUKUS provided support for an Australian nuclear submarine program, as well as cooperation and interoperability on “cyber capabilities, artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, and additional undersea capabilities.” Two months later, then-Australian Defence Minister Peter Dutton reinforced his belief, with minor caveats, that the island nation would support an U.S. defense of Taiwan. Given Chinese economic coercion against Australia, a Chinese-led East Asian order is not in their national interest. Australia should welcome an allied Indo-Pacific Task Force to deter China and streamline combined action.

The United Kingdom may be more of a challenge, as it navigates a post-Brexit role for itself while its global ambitions remain rooted in its history. While AUKUS is not specifically a mutual defense pact, it certainly indicates British focus on the region along with the 2021 HMS Queen Elizabeth carrier deployment. In addition, former Prime Minister Boris Johnson critiqued the People’s Liberation Army Air Force's incursions into the Taiwanese air defense identification zone (ADIZ) and projected Chinese intentions over Taiwan based on the Western response to Russia invading Ukraine. Current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak further declared the “‘golden era’ of [British] relations with China is over,” and further stated, “we stand ready to support Taiwan, as we do in standing up to Chinese aggression,” while refusing to rule out sending arms to Taiwan. Extending the cross-Atlantic “special relationship,” to cement a more permanent Indo-Pacific role also should be in the UK’s interest.

Critics may argue that it should be India in this position, given the Indo-Pacific focus, but this likely is flawed. While the diplomatic “Quad” did agree that “unilateral changes to the status quo with force like this should not be allowed in the Indo-Pacific region,” after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, India consistently abstained from voting in the United Nations to condemn Russia. The world’s most populous democracy has long pursued a non-aligned stance post-independence, and participating in the CJTF would likely be interpreted both in New Delhi and Beijing as a far more assertive and uncharacteristic alignment with the West against China.

Japan maintains its post–World War II mutual defense treaty with the United States, but its national constitution affects its hypothetical support for an ABJA CJTF. The 1947 Constitution’s Article 9 “renounces war . . . and the threat or use of force as the means of settling international disputes,” driving the military forces to be called [Domain] “Self-Defense Forces,” rather than an army, navy, or air force. Constitutional interpretations have evolved, toward a belief that “offensive” (rather than all) wars are unconstitutional, along with a mid-2010s interpretation allowing for overseas operations in collective self-defense. But domestic realities of foreign realpolitik continue shifting. In 2021, then-Defense Minister Nobuo Kishi directly connected the peace and stability of Taiwan with Japan, followed by a doubling in defense spending in late 2022. Further, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the late former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe argued that Japan should debate a nuclear weapon–sharing program similar to NATO, a topic previously unthinkable given Japan’s history. Japanese support of a standing CJTF likely would require a constitutional amendment but should be in line with its national interest.

Within the United States, Admiral Sam Paparo, Commander, Pacific Fleet (CPF), addressed the question of a US-Japan CJTF, relaying that INDOPACOM Commander, Admiral John Aquilino, “has directed Pacific Fleet to operate with Japan as if it’s a JTF.” The CPF commander added that existing cooperative deployments feel like daily joint and combined operations, so he would not presently recommend a U.S.-Japan JTF. Despite these comments, Admiral Aquilino, while onboard HMS Prince of Wales for the 2021 Pacific Future Forum Keynote, argued that defending a rules-based order required a combined force that was expeditionary, operated in campaigns, and could prevail across theaters and asynchronous timeframes. To underscore the increasing risk conflict in the Indo-Pacific, Admiral Aquilino recently stated in an interview that, “the current environment is probably the most dangerous I’ve seen in 30 years of doing this business,” adding, “Everything needs to go faster. [Everyone needs] a sense of urgency, because that’s what it’s going to take to prevent a conflict.” We must take these warnings seriously.

The 56-day failure of ABDACOM demonstrates that multinational high-end combat is not a pickup game. Photo exercises, trilateral engagements, and basic operations do maintain relationships. However, a rapid, flexible, and integrated military response to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan is a categorically different tactical and operational challenge—one INDOPACOM and its allied equivalents should test and sustain beyond wargames and staff planning.

The ABJA CJTF: Why Now and What For?

A future Chinese incursion to reclaim parts or all of Taiwan could vary widely in how kinetic or how broadly the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) advances. Nonetheless, policy experts and senior military officials have projected legitimate concern about the U.S. military’s ability to intervene on behalf of the island democracy. Any military or combined force must be able to rapidly respond to a changing environment, especially in a Taiwan scenario—and the weapons, systems, and networks of today are far faster than those the Japanese employed in World War II. An ABJA CJTF helps increase the speed of that response.

By the mere act of creating a CJTF between the four nations, each of its political-military leadership would have to replicate the work of the Arcadia Conference, only it would be done without the constant threat of an enemy advancing in wartime. With a unified command structure at the intersection of the strategic-political military organization, the operational issues could be identified, tested, and analyzed across each nation’s force structures. As opposed to ABDACOM’s formation during the war, an ABJA CJTF could do regular, pre-war, integrated high-end warfighting exercises across the theater, while synthesizing national war plans, and further strengthening the staff linkages between each country.

Of note, this CJTF likely should not constitute a cooperative mutual defense treaty, as this may be seen as too great a step in a geopolitical environment still shifting as a result of interstate war returning to Europe with Russia and Ukraine. An initial framework worth consideration is in the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), Central Command, the 34 nation coalition formed in 2002 to organize allied response in the region. The flexible organization does not bind nations to a fixed political or military mandate. CMF works principally on the “unit[y of] their desire to uphold the international rules-based order by protecting the free flow of commerce, improving maritime security, and deterring illicit activity by non-state actors in the CMF Area of Operations.” The United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, and the United States have all made commitments to the same rules-based order and a free and open Indo-Pacific, so framing a coalition around this order and the ability to respond to crisis may prove a sufficient foundation for further coordination. While the ABJA nations may prove the most steady pillars in any modern coalition, the CJTF should leave space for the inclusion of other NATO members with Pacific interests, like France and Canada, along with regional partners like the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, and India, should their national incentives further encourage deeper cooperation with the West.

At the operational level, “jointness” can be a persistent challenge within even the U.S. military. ABJA’s forces must do what Admiral Hart and General MacArthur could not, beyond a week before the war: integrate air and space forces to execute maritime strikes, and support intelligence, reconnaissance, and targeting (ISRT). Ahead of a hypothetical conflict, ABJA must integrate its maritime services and self-defense forces, as Admiral Hart aspired to, whether under distributed maritime operations or another concept. An ABJA CJTF operating model must provide for the missile defense of each nation, especially Japan and Australia, from which forces would likely be deployed into the theater. Absent this comprehensive and integrated defense plan, nations may break down to the disunity of ABDACOM, with the U.S. focused on the Philippines, the British on Singapore, the Dutch on the NEI, and the Australians on Darwin. Lastly, ABJA must prioritize logistics sustainment over the Pacific theater. For ABJA’s coalition of maritime nations to stay strong and relevant in a broader conflict, the force needs an integrated policy to sustain their national maritime trade, fuel, and materiel.

Just as ABDACOM sought to use the commanders already in theater in their roles, the ABJA CJTF should start simply by designating present operational leaders across each military and service in a dual-hat role. The United States need not be the sole commander of allied forces across each service, and it would be prudent to balance command functions nationally. But these are arguments and wartime habits of mind to establish now. Furthermore, if the United States, Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom can credibly demonstrate this task force operating within the Indo-Pacific, it may be the best example allies can offer of “integrated deterrence,” thereby raising the costs to a Chinese invasion and broader regional attack.

While the United States and its allies do not seek war, the CJTF could streamline the execution of national wills and international commitments. If the allies want to deter or deny Chinese aggression, now is the time to learn from ABDACOM’s annihilation by building a more unified coalition ahead of conflict. If we want peace, we must prepare for war.

1. Ian W. Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company Inc. 2012), 233.

2. Toll, Pacific Crucible, 233.

3. Toll, 174.

4. Toll, 182.

5. Toll, 188.

6. Toll, 188-189.

7. Toll, 190.

8. Toll.

9. Toll, 191.

10. Toll, 252.

11. Thomas C. Hart and Charles Culbertson. “War in the Pacific: End of the Asiatic Fleet and the Classified Report of Admiral Thomas C. Hart,” Staunton History (2013), 1.

12. Hart and Culbertson, 17, 30.

13. Ibid. Page 30-31.

14. Hart and Culbertson.

15. Hart and Culbertson, 34.

16. Hart and Culbertson, 36.

17. Hart and Culbertson, 56.

18. Hart and Culbertson, 58.

19. Hart and Culbertson, 65.

20. Hart and Culbertson, 68.

21. Hart and Culbertson.

22. Hart and Culbertson, 69–70.

23. Hart and Culbertson, 73–76.

24. Hart and Culbertson, 82–83.

25. Hart and Culbertson, 86.

26. Hart and Culbertson, 98–99.