The second major U.S. Navy encounter with the Spitfire occurred during preparations for D-Day—the invasion of the Normandy coast of German-held France on 6 June 1944. The Anglo-American invasion was the largest amphibious operation in history. The U.S. warships escorting the assault forces and providing gunfire support were three battleships, three heavy cruisers, and 40 destroyers.

The battleships and cruisers carried Curtiss SOC Seagull and Vought OS2U Kingfisher floatplanes for gunfire spotting. These were rugged and reliable aircraft; however, the threat of German fighter aircraft over the invasion area led to concern about their vulnerability.1 The Allied amphibious operations in the Mediterranean in 1943 had shown the need for more-capable aircraft for gunfire spotting in the face of defending enemy fighters.

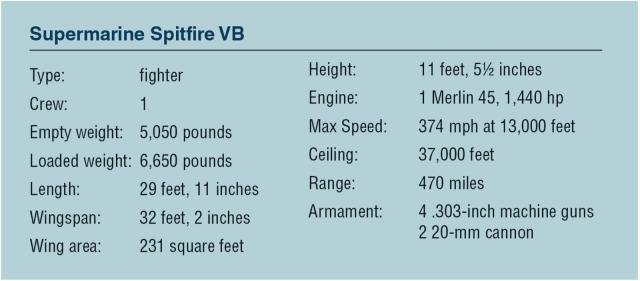

Accordingly, for the D-Day invasion, 17 pilots from the cruiser and battleship observation units were trained to fly Royal Air Force Spitfire VB fighters. The U.S. Navy considered using U.S. Army Air Forces (AAF) fighters for gunfire spotting, but first-line AAF fighters were not available. The Spitfires, although outdated as first-line fighters, were far more survivable than the Navy’s floatplanes, being superior in speed, maneuverability, and firepower. Accordingly, Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 7 was established. (Some sources incorrectly list the unit as VOS-7.)

The VCS-7 pilots trained with the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group, which was flying “Spits” from the Royal Air Force airfield at Middle Wallop in Hampshire, England. In addition to spotting, the syllabus included defensive fighter tactics, navigation, and formation flying. VCS-7 became fully operational on 28 May 1944 and moved south to Royal Naval Air Station Lee-on-the-Solent, its new home base on the English coast.

Ten squadrons at the air station were tasked with gunfire spotting or tactical reconnaissance for the Normandy invasion: five Royal Air Force, four Royal Navy, and VCS-7. VCS-7 was provided some Seafires—the carrier-based variant of the Spitfire—in addition to the Spits.

The VCS-7 missions began on 6 June:

Typical spotting missions utilized two aircraft. The lead plane functioned as the spotter. The wingman, or “weaver,” provided escort and protected the flight against enemy aerial attack. The clocking, or ship control, method was utilized on the majority of spotting sorties. . . . Poor weather forced the spotter to operate between 1,500 and 2,000 feet. Occasionally, missions were flown at even lower altitudes. Drop tanks were used to increase range. A typical spotting sortie lasted close to two hours. This provided 45 minutes on station and one hour in transit.2

Although Luftwaffe action was not as bad as had been anticipated, four VCS-7 pilots came under attack by German fighters but avoided being shot down. Antiaircraft gunfire was responsible for the only confirmed VCS-7 loss: Lieutenant Richard M. Barclay, senior aviator on board the USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37). His wingman suffered severe damage to his aircraft but managed to return to base. The official VCS-7 combat report mentions only the loss of Barclay at Normandy, but there may have been more casualties. In The Seafire: The Spitfire That Went to Sea (Naval Institute Press, 1989), author Dan Brown claims seven squadron aircraft lost to enemy action plus one operational loss during the unit’s 209 sorties.

By 26 June the Allied invasion forces had advanced inland beyond the range of battleship and cruiser guns, and VCS-7 was disbanded. Its pilots returned to their ships and their floatplanes, having been awarded nine Distinguished Flying Crosses, six Air Medals, and five Gold Stars.

1. See N. Polmar, “Historic Aircraft” [SOC Seagull], Naval History (August 1997), 76; and “The Eyes of the Fleet” [OS2U Kingfisher], Naval History (December 2002), 14.

2. Steven D. Hill, “Invasion! Fortress Europe: Naval Aviation in France Summer 1944,” Naval Aviation News (May–June 1994), 32–33.