In a dangerous era of great power competition, the stakes were high. A deeply indebted nation was extracting itself from a less-than-decisive war, and its future economic prosperity was challenged. Its main rival was a continental power with the world’s largest economy, vast resources, and three times its population. The adversary sponsored proxy forces and terrorists that attacked along the periphery of its partner’s frontier. The country’s political leadership was divided on which threat was the most important and how to respond. The nation could not do it all, and it had no coherent strategy for building up and using its armed forces.

This may sound like today, but it actually is drawn from one of history’s great strategic rivalries: the conflict between Great Britain and France in the mid-18th century known as the Seven Years’ War—or, in the North American theater as the French and Indian War. Recent scholarship in strategic rivalries often overlooks this example.1

That is unfortunate, because while historical analogies are never perfect, this one contains numerous continuities that possess applications for the present-day United States. Great Britain’s strategy in particular deserves detailed study.

Strategy is hard to get right, and many factors constrain the attainment of ambitious goals. Sir Lawrence Freedman says strategy is “about getting more out of a situation than the starting balance of power would suggest. It’s the art of creating power.”2 No statesman proportioned aspirations to the constraints of his day better than William Pitt.

Pitt was the rarest of combinations: a brilliant strategist with an eye for talent and an aggressive politician. His strategy—what he called a “system”—had five elements:

- North America should be the main theater for a strategic offensive to eliminate French influence in Canada.

- Prussia should receive large grant subsidies to sustain its army, protect Hanover, and keep the French occupied on the European continent.

- The Royal Navy should blockade French Atlantic ports to deny freedom of action to the French fleet.

- Amphibious raids should keep the French Army tied down and pull resources away from potential use against London’s Prussian ally.

- Other colonial possessions in the Caribbean and West Indies should be targeted for seizure to weaken French economic interests.3

Pitt outlined critical lines of effort—military, organizational, and diplomatic—with a constellation of allies including not only Hanover and Prussia, but also various Native American tribes. Prioritizing these elements, stressing Great Britain’s strengths, and applying them against the identified vulnerabilities of his adversary guided the logic of London’s strategy.

Applied Strategy

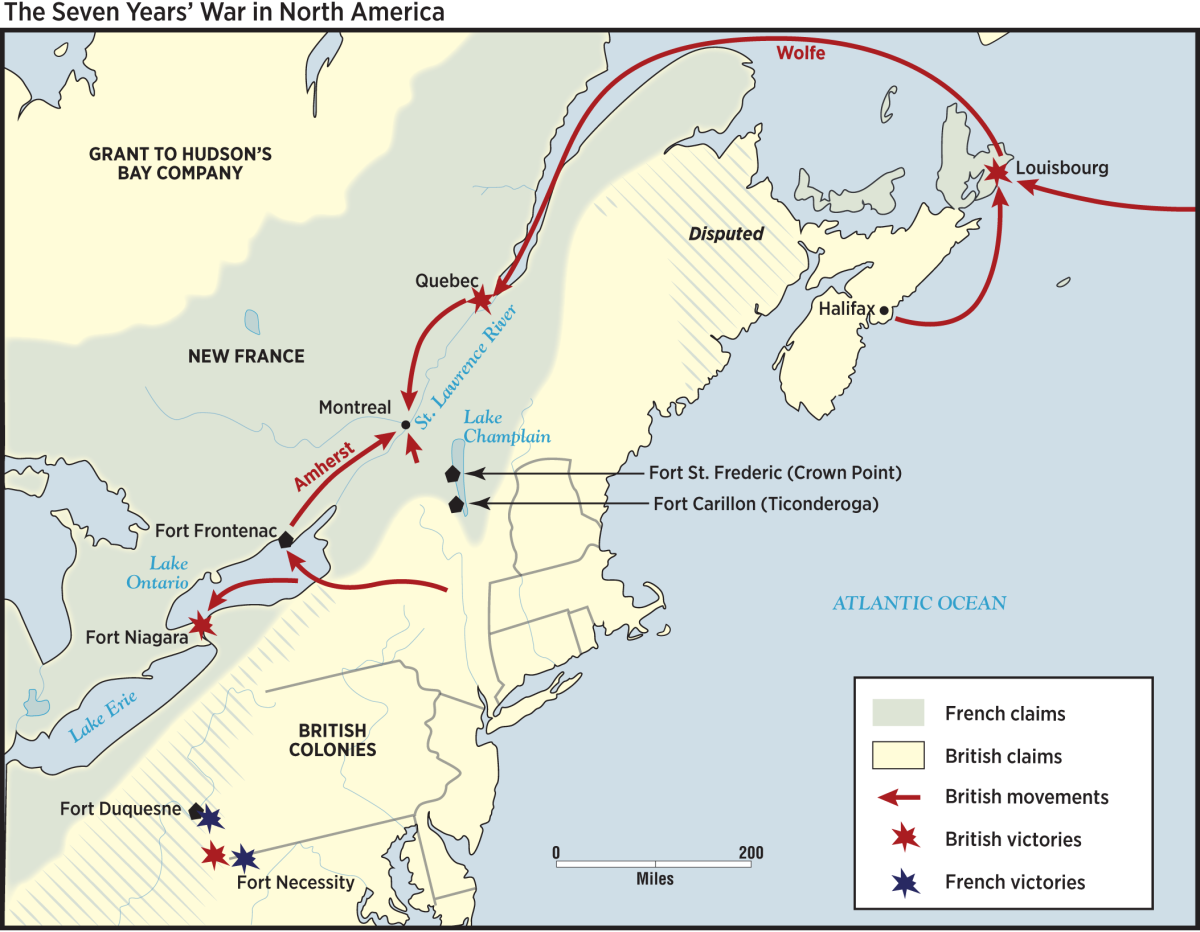

Pitt’s approach, however, was not immediately effective. In 1757, London faced defeat in both North America and elsewhere. The most embarrassing example was the Royal Navy’s failure to prevent the French Navy from reinforcing Louisbourg in the French colony of Ile Royale (or New France, part of modern Nova Scotia), when poor communications and weather wasted an entire campaign season.

In 1758, with Pitt’s clear instructions and more aggressive commanders, the tide began to turn in Britain’s favor. France hoped to use naval reinforcements to hold Louisbourg’s port and citadel, but the British blockaded the French fleet sailing from Toulon. This left the French with only 11 ships in Louisbourg to oppose the British. There, the governor of Ile Royale, Augustin de Drucour, had 3,500 regulars and approximately 3,500 marines and sailors to resist a force twice their number.

Meanwhile, British forces assembled at Halifax, where army and navy units spent a month training. The fleet, under command of Admiral Edward Boscawen, consisted of 40 men-of-war and 150 transport ships. The amphibious force included almost 14,000 soldiers—mostly regulars—led by Major General Jeffrey Amherst and Brigadier James Wolfe.

On 2 June 1758, the British force anchored three miles from Louisbourg. Bad weather prevented an immediate landing and siege. At daybreak on 8 June, Wolfe led a landing force ashore at Freshwater Cove. French defenses initially were effective, forcing Wolfe to plan a retreat after heavy losses. At the last minute, however, his light infantry found a protected inlet, and Wolfe secured a beachhead. Outflanked, the French withdrew into the fortress.

The British slowly built up an artillery battery of 70 field pieces, naval guns, and mortars ashore to reduce the city’s fortifications. On 19 June, the British batteries opened fire. The long siege had begun.

Chance plays a role in all wars, and this campaign was no different. A lucky round from a British mortar hit the French 64-gun ship Le Célèbre on 21 July, starting a raging fire that carried over to two other ships, L’Entreprenant and Le Capricieux. The destruction of powerful L’Entreprenant (74 guns) was a huge loss. Two days later, British “hot shot” (heated cannon balls) hit and destroyed the fortress’s headquarters, known as the King’s Bastion. Then Boscawen sent in a cutting-out party to attack the remaining French ships. Under cover of fog, the Bienfaisant was captured and the Prudent burned, eliminating resistance in the harbor. The French formally surrendered the next day, depriving France of any major North American naval base.

Québec

British operations in North America picked up momentum. Army forces seized Niagara, Ticonderoga, and Crown Point in 1759, giving the British control of the Great Lakes. Along with Louisbourg, these moves created an opening into the St. Lawrence River—and France’s major outposts at Québec and Montréal. Under the command of Vice Admiral Charles Saunders, some 22 ships-of-the-line, 13 frigates, and 55 support vessels navigated the treacherous waters of the St. Lawrence to bring Wolfe’s force into position below the Plains of Abraham to attack Québec in September.4 On 12 September, Wolfe got seven battalions of infantry up a small path in the night, as well as a pair of 6-pounders hauled up by sailors. Saunders’ improvised gunboats provided mobility, fire support, and essential supplies for Wolfe’s daring assault.5

On the morning of 13 September, Wolfe arrayed his forces in line, albeit better positioned to make than to receive an attack. French Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm could have calmly awaited the British behind his entrenchments but elected to give battle. In this way, an irregular war in North America was won—somewhat ironically—in the most traditional way: two infantry lines standing across from each other firing muskets.6 Both Wolfe and Montcalm were mortally wounded. Yet it was a classic combined operation. As one historian has stressed, “It would be impossible to exaggerate the importance of the part played by the British navy in that operation.”7

Quiberon Bay

As 1759 went on, France realized it was losing and decided to strike directly at Great Britain. It began amassing troops and transports in coastal ports to invade. Spies informed the Admiralty, and the Royal Navy kept the French fleet under close blockade. Paris ordered the Marquis de Conflans to sail from Brest to escort the amphibious force to Scotland. Back at the English port of Torbay after months of an arduous blockade, Sir Edward Hawke was ordered to intercept Conflans. He caught the French fleet on 20 November outside Brittany’s Quiberon Bay.

Like Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson 46 years later, Hawke had supreme confidence in his captains and their well-trained crews. He elected to follow Conflans past dangerous shoals inside the bay to get at the French. Instead of slavishly obeying the Royal Navy’s rigid “Fighting Instructions,” Hawke unleashed his subordinates.8 The resulting melee destroyed and scattered the French. Conflans lost seven ships, and the rest were bottled up.9

More important, the French Navy was eliminated as an effective fighting force, and its ability to threaten England was dashed. With the cream of French naval power beached or burning, the British were able to expand globally. Alfred Thayer Mahan called it “the Trafalgar of this war.”10 In some respects, the action was more important strategically than Nelson’s iconic victory because it prevented an invasion.11

Montréal

The British Army continued its campaign in Canada the next year, with the Royal Navy holding Louisbourg and the St. Lawrence, blocking French reinforcements or supplies. More than 18,000 men maneuvered into Canada to take Montréal along three waterways: Brigadier James Murray’s small army of 3,800 men moved up the St. Lawrence from Québec; 3,400 soldiers under the command of Brigadier William Haviland arrived via the Richelieu River; and a final contingent moved on the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario, with Major General Jeffrey Amherst at the head of 11,000 men. This three-way pincer made Montréal indefensible and, on 8 September 1760, the city surrendered. Amherst’s victory left the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon as the only remaining French possessions in Canada.

Great Britain attained its strategic objectives by combining means that expanded the character of the competition. The British out-partnered, out-innovated, out-maneuvered, and—when necessary—out-fought the French. If the essence of strategy is creating more power out of a situation than the initial conditions suggest, then Pitt was its master. The year 1759 became the touchstone historians use to date Great Britain becoming the globe’s most powerful nation, though the war continued for several more years, with victories in the West Indies and India cementing Great Britain’s status as a global power for the next century and a half.12

Why Did Great Britain Succeed?

At the end of the war, Great Britain was the established great power. True, the seeds of American independence had been sown, and London was in debt. But Britain’s imperial reach and power were durably in place. It is instructive to understand why this strategy was effective.

- Competitive strategy. The British approach resembles what now is called a competitive strategy.13 These operate over long periods, usually in peacetime, an approach that pits national security enterprises—including intelligence, information operations, acquisition, research laboratories, etc.—against each other at the institutional level. The most important matter is to discern in which domains (sea, air, or land) or functions one can gain and sustain a comparative advantage. The cardinal rule is to pit strength against weakness to gain and hold that advantage over time. Thus, the British exploited their vast maritime power and sought to avoid fighting France in conventional ground combat in Europe.

- Diplomacy. Pitt understood the need to compete in the political dimension of strategy. He consciously sought to bolster both the strength and number of allies he could count on to help advance England’s interests in Europe. For maritime powers, alliances historically have proven an essential aspect of grand strategy.

- Prioritization. Grand strategy is all about balancing risk and keeping aims, resources, and interests aligned. Prioritizing strategic effort is the essential task of the leader. Pitt was maniacal about priorities and strategic alignment, despite the uncertainties he faced. He was clear on his priorities about theaters, seeking decisive results in North America first, containing France on the continent, and then tackling the West Indies.

His selection of which domain to focus on was equally clear. Pitt was a member of the “blue water” school in British circles, and he deliberately exploited the strong “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy to block France’s ability to operate in the Atlantic and the Channel. This leveraged Britain’s substantial maritime assets. In terms of total warships, merchant fleet, shipyards, and naval stores, Britain operated with clear superiority.14 The country started with 130 line-of-battle ships, while France could claim less than half that number—only 63 in commission and many lacking armaments.15 At the end of the war, the Royal Navy had expanded by 30 ships while France’s fleet was reduced by a dozen. - Multidomain or combined operations. In addition to classic blockade, the British exploited their naval prowess with amphibious descents. Prussian King Frederick II (Frederick the Great) requested that the British execute these operations to keep the French distracted and dispersed.16Mahan believed “these operations . . . had but little visible effect upon the general course of the war.”17 Yet they created a strategic effect by bogging down thousands of French forces. One estimate suggests British raids on coastal towns along the French coast tied up 134 infantry battalions and more than 50 cavalry squadrons that otherwise might have fought Prussia. These dynamic force employment operations generated dilemmas for France by expanding the competitive space it had to worry about.18

- Modernization and reform. Another line of effort was military reform. First Lord of the Admiralty Admiral George Anson built up the naval yards, drove out corrupt contractors, enhanced medical care, expanded the navy from 55,000 to 85,000 sailors, and streamlined fleet and ship designs. (See “The 74—the Perfect Age-of-Sail Ship,” February, pp. 6–7.) He also organized at-sea replenishment to support the blockade and improve quality of life and food (including beer) in the fleet.19 He added 30 companies of marines to support amphibious operations. Even at the time of his death in 1762, Pitt recognized that Anson should get the lion’s share of the credit for the Royal Navy’s sustained efforts over four oceans, telling the House of Lords, “To his wisdom, to his experience and care the nation owes its glorious successes of the last war.”20

History and Sea Power

Recent scholarship overlooks this significant period despite its status as the first global war.21 Yet classical strategists such as Mahan and Corbett were well aware of it. As Mahan noted, “At the end of seven years, the kingdom of Great Britain had become the British Empire.”22 The United States does not seek to establish a present-day imperium, but if it needs to understand in compelling terms the merits of a maritime-systemic strategic approach, this 250-year-old global competition warrants study. Britain’s success was predicated on the utility, mobility, and firepower of a lethal and well-supported fleet. France’s dilemmas were the natural by-product of London’s strategy and Britain’s wooden walls.

The U.S. Navy no longer sails under canvas on board ships planked with oak timbers, but the importance of sea power will rise in this century.23 The exercise of sea control will differ from the 18th century, but its value endures. Sea power’s strategic effect—controlling time, space, and economic activity on the oceans—remains invaluable, whether executed by a 74-gun, three-masted ship-of-the-line or a stealthy, nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarine.

As with Great Britain 160 years ago, the future of the United States will be determined by the “one sea.” As Admiral James Stavridis puts it: “We are an island nation, bounded by oceans and nurtured on the global commerce and strategic waterways of the world’s oceans. Without the oceans and our ability to sail them, we would be enormously diminished as a nation.”24 Great Britain’s leaders, led by Pitt and Anson, recognized this reality and acted on it wisely. History never repeats itself exactly, but it surely offers insights to draw upon.

1. At least three current histories overlook it: Williamson Murray, McGregor Knox, and Alvin Bernstein (eds.), The Making of Strategy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001); James C. Lacey (ed.), Great Strategic Rivalries: From the Classical World to the Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016); and Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich, (eds.), Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

2. Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), xii.

3. Adapted from Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (New York: Dover, 1987), 296.

4. Romanticized by Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (New York: Modern Library, 1999).

5. John B. Hattendorf, “The Struggle with France, 1689–1815,” in J. R. Hill (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 99.

6. Walter R. Borneman, The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 221.

7. Guy Fregault, quoted in Daniel Baugh, The Global Seven Years War, 1754–1763 (Harlow, UK: Pearson, 2011), 420.

8. Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York: Vintage, 2001), 381.

9. Andrew J. Graff, “Chaos Under Control: Lessons from Quiberon Bay,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144 no. 2, (February 2018): 40; Anderson, Crucible of War, 377–83.

10. Mahan, Influence of Sea Power, 304.

11. Brian James, “The Battle That Gave Birth to an Empire,” History Today, (December 2009), 26–32.

12. Frank McLynn, 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004).

13. Thomas Mahnken (ed.), Competitive Strategies for the 21st Century: Theory, History, and Practice (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012).

14. For an overview of the naval position, see N. A. M. Rodgers, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815 (New York: Norton, 2005).

15. Mahan, Influence of Sea Power, 291.

16. Julian S. Corbett, England in the Seven Years’ War: A Study in Combined Strategy, vol. 1 (London: Longmans, Green, 1918), 148.

17. Mahan, Influence of Sea Power, 296.

18. Rogers, Command of the Ocean, 271.

19. Rogers, 281.

20. Quoted in Arthur Herman, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the World (New York: Harper, 2004), 292.

21. William R. Nester, The First Global War, Britain, France, and the Fate of North America, 1756–1775 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000).

22. Mahan, Influence of Sea Power, 291.

23. Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century 3rd ed. (Oxon, UK: Routledge, 2013), 339.

24. ADM James Stavridis, USN (Ret.), Sea Power: The History and Geopolitics of the World’s Oceans, (New York: Penguin, 2017), 342.