_0.jpg)

Brown, Wesley A., Lt. Cdr., CEC, USN (Ret.)

(1927–2012)

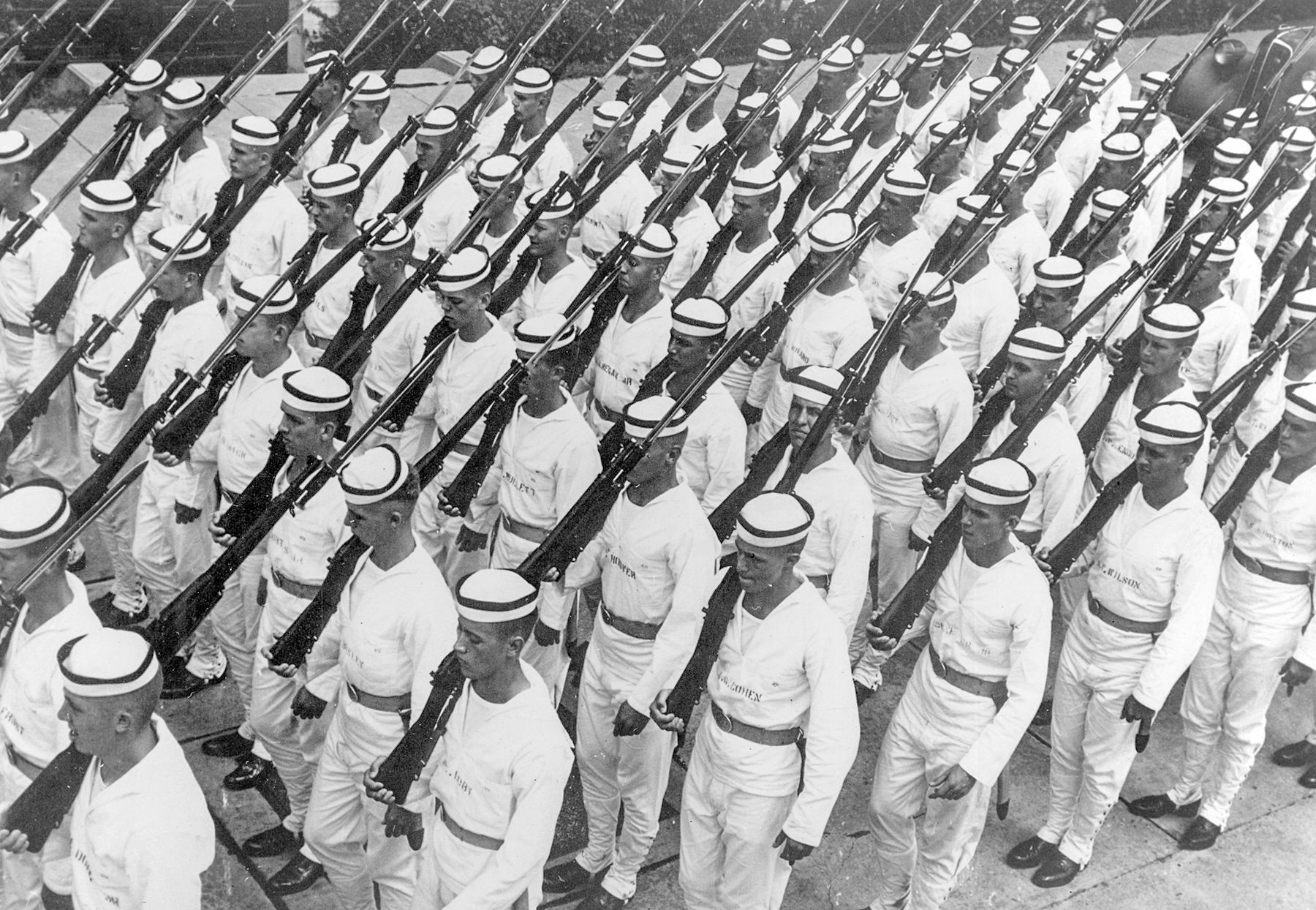

This oral history is particularly noteworthy, because it provides personal recollections from the first African American graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. Brown entered the Academy in 1945, a century after the institution was founded, and graduated in 1949. A handful of black midshipmen had previously been appointed to the school in Annapolis, but all were either pushed out or left of their own volition prior to graduation. Brown spent his youth in Washington, D.C., where he attended segregated Dunbar High and had part-time jobs working for the Navy and Howard University. He was able to succeed at the Naval Academy through a combination of his sunny disposition, academic ability, and perseverance. Following his commissioning in 1949 he had a temporary assignment at the Boston Naval Shipyard prior to undertaking postgraduate study in civil engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 1950-51. His subsequent duties as an officer in the Civil Engineer Corps included postings to Bayonne, New Jersey; Naval Mobile Construction Battalion 5 (NMCB-5) in the Philippines and Port Hueneme, California; the headquarters of the Bureau of Yards and Docks in Washington; the Construction Battalion Center, Davisville, Rhode Island; the public works department at the Barbers Point Naval Air Station in Hawaii, temporary duty in Antarctica; a tour at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; and final active duty service, 1965-69, at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn. During his time in the Philippines in the 1950s he had a substantial role in the construction of a new aircraft carrier pier in Subic Bay. In the early 1960s he had a leadership role as the Navy's Seabees did construction projects in the Central African Republic, Liberia, and Chad. Following his retirement from active naval service in 1969, Lieutenant Commander Brown worked in several capacities for the State University of New York system and subsequently did facilities and construction work at Howard University in Washington. In May 2008 the Naval Academy dedicated a new athletic field house named in Brown's honor. In his remarks at the dedication of the facility Brown said the naming of the new building symbolizes the Navy's commitment to diversity.

Excerpt

In this audio selection from his oral history, Lieutenant Commander Brown details the challenges he faced as a black midshipman at the Academy in the 1940s, recalling, “I’d take each day at a time . . . I said, ‘I’ve got to give the other guy the benefit of the doubt. Unless it is clearly obvious that this is a racial thing, I can rationalize this and say this is a plebe thing.’”

(Note: Due to edits, corrections, and/or amendments to the original transcription draft, there are some inconsistencies between the recording and the text.)

Paul Stillwell: Were you asking yourself questions as you went along: “Is it worth this pain and misery? Do I really want to be a naval officer?”

Commander Brown: Well, I don’t think I ever seriously thought of resigning. I took one day at a time.

I remember one day, however. I wasn’t feeling too well, and so I had good days and bad days. There were some days when everything went wrong. I added up the number of days that were left before the scheduled graduation and there were a lot of days; it was over 1,000. I just thought, “Oh, God.” But, no, I don’t think I ever really did. I got a lot of mail from friends; I got wedding proposals with pictures. I ended up with some pen pals that I used to write to quite often, a young lady in Norwalk, Connecticut, and another one in Westerly, Rhode Island. And these were very encouraging. Of course, I heard from my mother and father pretty often, classmates from high school or different schools. So I was probably prepared to take a lot more than I actually experienced. As a result, I don’t think I ever really had to look back and say, “This wasn’t a good idea.”

I guess the thing that gave me the most fear was that I’d get too many demerits. I really had to sweat out those last few because I was pretty darn close.

Paul Stillwell: That was your plebe year you’re speaking of.

Commander Brown: Plebe year, yes. Pretty darn close. I think you're allowed 150 for the semester and 300 for the year, and I might have had 140, maybe even 145. And then I think the second semester was better. And I realized — well, I guess, as I said in the Post article, I made up my mind with regard to several things. One, I’d take each day at a time. I can write off today as a bad day and not carry that into tomorrow. Tomorrow was a separate day. Everything’s going wrong today; I’ve got a couple hours to go. There’s still time for some more disasters, you see. And I could laugh about it a little bit.

Secondly, I said, “I’ve got to give the other guy the benefit of the doubt. Unless it is clearly obvious that this is a racial thing, I can rationalize this and say this is a plebe thing.” And that other plebes were getting as much, if not more, as I was for whatever reasons or no reasons. So the plebe thing gave you a basis to rationalize it. And you kept so busy doing so many non-academic things that were associated with plebe status that you really didn’t have time to sit around and feel sorry for yourself. Plebe year was a busy year for everyone, and especially for me. So with the lights out at night and reveille in the morning, everybody had about the same amount of time. And I was probably better than most guys in terms of conservation of time.

As I told you earlier, I started getting up before reveille and going swimming. And that helped because when you hit that cold water in the morning — you don’t have to swim very many laps — although I wanted the word to get around that I was a good swimmer. [Laughter]

Paul Stillwell: Where has that myth come from? Do you have any idea?

Commander Brown: No. But then I’d come back about the time of reveille. Now I was wide awake for that first class, you see. So that helped, that helped. And it certainly helped, not only to have encouragement from the outside; it really helped to know that there were classmates—and upper classmen, in particular — who were rooting for me. And I could see that. You could see the little gleam, or the nod, or so forth. That was important — to know that not everybody was against you, because if that’s the attitude you take — you’re completely alone, nobody cares, everybody’s anti—you’re not going to make it.

Those are the same basic principles that apply in any human-relations situation. The young guy who’s the boss and most of the other guys are older. The young division officer trying to establish the proper rapport with the chief. And you can’t teach that at the Naval Academy. You can teach principles. It’s got to be an eyeball-to-eyeball thing. You’ve got to look that chief in his eyes, and you might see a little resentment there. You might see, “Oh, here comes another one. God, I should have put in my papers.” You have to be aware of the fact that you’re not the first ensign that guy’s seen. You also have to look at this relationship between the chief and the other petty officers, and the other men and where you stand in there. The guys are going to run to you and say, “The chief won’t let me do this.”

And to have you say, “Come here, chief, let him do that.” All of this is the same kind of stuff that I was in in a different situation, different set of circumstances, so you’ve got to play the thing by ear, you’ve got to have confidence. The division officer walks in there with confidence and doesn’t have to say to the chief, “I’m in charge,” because the chief knows this is a take-charge guy. All the difference in the world as to how you go in there. And no one can teach you that. You’ve got to feel it, and feel comfortable doing it. That’s what it’s all about.

Paul Stillwell: You had that feeling of comfort that you could make it that I’m sure sustained you. As you thought about those 1,000 days to go, did the thought cross your mind, “If I don’t make it, if I quit, that gives ammunition to all those critics who say that black people can’t make it”?

Commander Brown: Well, I don’t know. Hindsight is 20/20. I certainly felt an obligation in that regard, but at the same time, I also felt that should I ever feel that this was not for me, this was not the career I wanted, this was not worth it to me personally, I felt I had the right as an individual to resign, to get out and to do it fast rather than to waste three years or something like that. I never reached that point. But somehow I had the feeling that I really wasn’t representing anybody in that sense. I felt that this was my decision, it was my career, and I could change courses.

Now, I guess I hadn’t really thought about it. There was a rumor going around that I was being paid by the NAACP some fantastic amount—never heard the amount—and that every day that I stayed there, I got a lot of money from them. So that I was strictly a mercenary. A few guys said that they were going to make sure that I earned my money. Well, this, of course, was ridiculous. But then I said, “Would I do something like that for money?” I said, “I don’t think I could; I don’t think I could.” It would have to be for my own purposes, and so it would have to be an awful lot of money to get me to do something I didn’t want to do. That’s when I said, “I think this is what I want to do.”

And then those questions, “Well, why are you here? The Navy doesn’t need you; there’s no career there for you.”

Then I said, “Yes, there is; yes, there is. This is my career. This is for me, not for somebody else.” I’ve never tried to talk anybody into going to the Naval Academy. I’ve talked to a lot of people; I’ve probably talked more people out of it than into it. Only because of motivation, okay? There’s been one black graduate of the Naval Academy, okay? The rest should be there because they want naval careers, and if that’s not your goal at the end, you’re not going to be very happy, and it’s not going to be worth it. I talked to a lot of people about that. You don’t need to prove anything; it’s already been proven. And a lot of people go for the wrong reasons. As a matter of fact, you get a commission a lot easier by going to a civilian school and going to OCS, or taking NROTC and getting a commission. So the stuff that we have there is for producing naval officers. In the old days we didn’t have any choice of what we could take. You can do that in college; you can avoid professors. I don’t know who my professor’s going to be next year. I don’t have a choice. They can’t pick easy subjects.

So I think I can honestly say that while I was aware of the fact of establishing a precedent, there was the difference between West Point and the Naval Academy, and I opted for the Naval Academy, not only because no one had done it, I was more engineering inclined and I thought the Navy offered a better chance there. My high school yearbook said that I wanted to be a civil engineer. Of course, my wife also said that under hers. I went to college at Howard, and I was an electrical engineering major, still interested in the engineering part of it. I didn’t go to the Naval Academy expecting to end up in the Civil Engineer Corps. I expected I would be a line officer. The reason I guess I got over part of the bad effect of the carrier cruise — of course, I did well in aviation, I liked the subjects; I enjoyed the flying—but when the chance came for Civil Engineer Corps, I took it. Get additional education. If I didn’t like the Navy, I could get out, and I would have further professional training that would be worthwhile.

Paul Stillwell: Well, that was really hedging your bet then.

Commander Brown: Oh, yes, it was. It was. But they only took 18 of us — six from each third of the class. I’ve forgotten what the percentage was, it was 3% or something like that. So I really didn’t expect to get it, but I figured, what the heck, I might as well try. So I was quite surprised when I got it; otherwise, I was perfectly happy to go into the fleet.

About this Volume

Based on nine interviews conducted by Paul Stillwell from December 1986 to February 2008. The volume contains 481 pages of interview transcript plus a comprehensive index. The transcript is copyright 2010 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use.