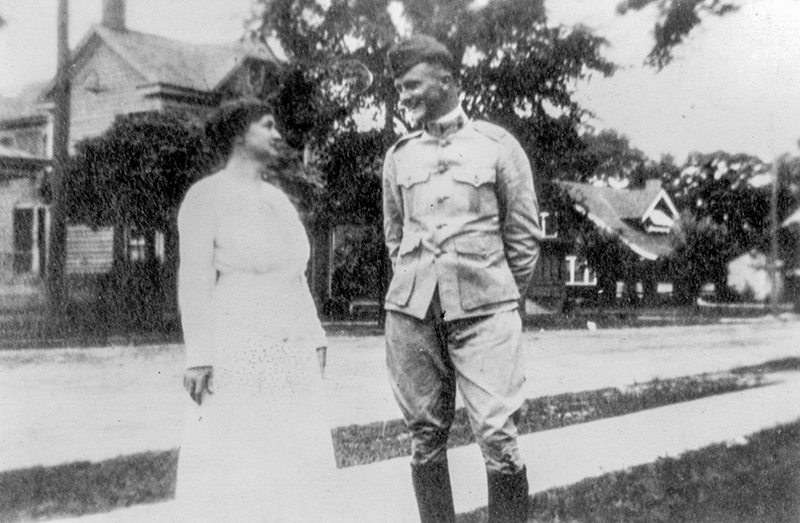

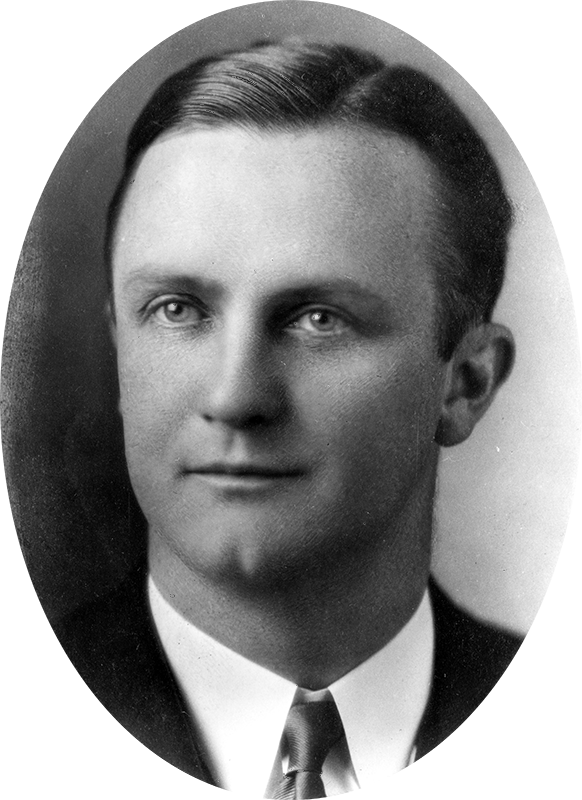

Darden, Colgate W. Jr., The Hon. — Marine Corps Aviator, Member of Congress

(1897–1981)

Darden's life was one of public service, as a U.S. Congressman, governor of Virginia, president of the University of Virginia, and delegate to the United Nations. This short volume concentrates on two facets of his career – as a Marine and a Congressman. A Marine Corps aviator in World War I, he went through boredom in France waiting for planes to become available, then was seriously injured in an aircraft accident that killed Marine Medal of Honor recipient Ralph Talbot. In the second interview in the oral history, Darden discusses his service on the House Naval Affairs Committee in the 1930s and 1940s and recalls some of the issues of importance at the time: dealing with the Japanese, fortifying Guam, and preparing the Navy for war. He provides insights on personalities such as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Representative Carl Vinson, and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz.

Interview

In this excerpt from his first interview with Dr. Mason on 24 September 1969 at the Army and Navy Club in Washington, D.C., Darden describes the near-fatal airplane crash shortly before the end of World War I that ended his active-duty career and killed his pilot, Medal of Honor recipient Ralph Talbot, USMCR.

Mr. Darden: We got equipment just toward the end of the war, and it was then that I was injured. So I was swept out and left.

Dr. Mason: Tell me about your injury.

Mr. Darden: I was over at Squadron Three with a friend of mine, Ralph Talbot, and I went for a flight.* Talbot had been in a fight a day or two before, a few days before, and he had gotten his plane shot up right badly.** He had had it in the shop and had gotten it out. He and I had been in nine together. We were friends, and he had asked me to come along and go for a flight with him. I got in the plane and got in the gunner’s seat. It was a DH-4. And for some reason I didn’t fasten my belt. I just sat down on the gunner’s seat on the strap that the gunner used as a seat in the mount that revolved and carried the machine gun. The gun wasn’t mounted. We ran down the field, and there was trouble with the motor. I realized there was trouble. It wasn’t tuned up well. Ralph came back, and then the second time he went down he got the plane about six inches off the ground and ran straight into a heap of earth that had been thrown up for a bomb pit at the end of this field. I think he must have known it but had forgotten about it. It was a bomb storage pit, dug at the end of the field, with earth thrown on the side as they dug this trench or hole. The DH locked its landing gear in the earth bank, and the plane went over into the pit. Talbot was killed, but I was thrown clear almost as though I had been thrown from a catapult. I was sitting in the second seat in the DH-4 and when she went over on her nose and turned over, she caught fire. It projected me straight out, just like a stone being thrown out of a catapult. It threw me 125 feet into a wheat field. Well, it was an awful fire, and the squadron boys ran down there to try to get us out and also to try to pull the bombs out of the way, because they didn’t want them catching fire and exploding. They thought we both had been killed. They didn’t see me take off on my flight, because the plane and the smoke interfered. I had been shot out at almost a dead level. I didn’t go up and come down.

Dr. Mason: You were like a missile.

Mr. Darden: I was just like a missile shooting at shoulder level, and it just shot me down on the ground. Walking around the field later on, they came across me and picked me up and put me in a car and took me over to the British hospital at Calais. There I stayed for a week or ten days or so. It was the end of October, the 25th, that I was injured. I was transferred from Calais to London.

Dr. Mason: You had broken bones?

Mr. Darden: I had the right side of my face broken in completely. My head went over and hit the escarpment of the gun, and it crushed the side of my face. It dislocated my spine, the upper part of the spine, and paralyzed me. So it was some time before I could move. I was turned over by attendants at the hospital. They kept me on the bed and moved me around. Then, on my left leg, the flesh was just opened down to the bone, I think. My leg must have hit some blunt object. It didn't break the bone but simply pressed aside the flesh and opened it along the bone for two or three inches.

Dr. Mason: It certainly was providential that you didn't fasten your flying belt.

Mr. Darden: Absolutely saved my life. Had I fastened that flying belt, I would have been burned. There was no way they could have gotten me out and I would have been . . .

Dr. Mason: Did Talbot burn?

Mr. Darden: Talbot did, but I think he was killed immediately, because in the DH-4, one of its difficulties was that its large fuel tank of 90 gallons in a wreck would slide forward on the pilot. He was sitting in the pilot's seat, in the forward seat, which was the pilot's seat. I was sitting in the gunner's seat right behind the wings. It was a biplane. There was a 12- or 14-gallon auxiliary tank in the wing just above the pilot's head, and in a crash that thing would come down and they would have a fire. That’s what burned the plane up, and the 90-gallon tank tore out and went along with me for a distance, not as far. But the auxiliary tank caught fire on the impact. I think Talbot was killed instantly by the large tank moving forward and tearing out of the plane, because we hit with enormous force. We were off the ground, and I expect we were going 100 or 115 miles an hour and gaining headway. We were a little bit off the ground when we hit.

Dr. Mason: Did they succeed in putting out the fire before the bombs exploded?

Mr. Darden: They got the bombs away from the fire. They got the bombs pulled away and there were no explosions.

Dr. Mason: Tell me a little about the airfields of that day.

Mr. Darden: The airfields were simply graded fields, farming fields. There was no surfacing on them to speak of.

Dr. Mason: No surfacing, no concrete or anything?

Mr. Darden: The most unbelievable field that I have ever seen or heard of was the field that we trained on in Miami. The dust there, the sand was six or eight inches deep. The planes would struggle terribly in taking off. You would open them full throttle, and they would struggle mightily at just a few miles an hour until they could extricate themselves and get up to the top of the sand and then coast along to take off. I don’t know if you are a duck shooter. If you notice how a duck flies out of water, they run along a little way, gain headway, and then get up. Well, these planes would labor terribly and go slowly until they could finally pull themselves out and get away.

Dr. Mason: Did that necessitate a very long runway?

Mr. Darden: Fairly long, yes. They were not like the runways are today, because the planes lifted off much more quickly. But the runways in France, the runways that we had were very imperfect. But then again, the planes weren’t terribly heavy. The runways could be graded and fixed out.

Dr. Mason: But this meant that in bad weather, the runways . . .

Mr. Darden: You were practically out of commission then.

Dr. Mason: They used concrete as paving in those days.

Mr. Darden: I would expect that in the larger fields they had concrete runways fixed up. I think with us they probably had just some surfacing material that hardened the earth somewhat. But there again we had so few planes, and the war ended before we were equipped. It ended before the field could be put in shape really for use.

Dr. Mason: So this really was the end of your . . .

Mr. Darden: This was the end of my war career. I don't reckon anybody ever made a more modest contribution to the First World War than I made. But I went along, and I saw a lot, and I served with a lot of people who were good and interesting people and many of whom I have kept up with over the years. Many of them are dead now. It's startling how many are dead. We had our 50th reunion a year ago next month in Miami. We left there in 1918. We went back in 1968 for the 50th reunion and sat around and talked and lived over the old days. But there were not too many. A good many of them are gone.

* Second Lieutenant Ralph Talbot, USMCR.

** On 14 October 1918, eleven days prior to his flight with Darden, Talbot earned the Medal of Honor for his exceptional performance on a raid over Belgium. He was one of only two Marine Corps aviators awarded the Medal of Honor for World War I. The USS Ralph Talbot (DD-390) was named for him.

About this Volume

Based on two interviews conducted by Dr. John T. Mason Jr. in September and October 1969, the volume contains 79 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1984 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use