Eller, Ernest M., Rear Adm., USN (Ret.)

(1903–1992)

In the first of three volumes by a former Director of Naval History, Admiral Eller discusses his boyhood, midshipman years leading to graduation from the Naval Academy in 1925, duty in the battleships USS Utah (BB-31) and USS Texas (BB-35), and the submarine USS S-33 (SS-138). In the 1930s, he served two tours on the faculty of the Naval Academy, where he made the study of leadership a project. A characteristic of this volume is the admiral's ability to place events in the narrative into the broader context of history. For instance, in his discussion of duty with the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, he provides detailed descriptions of various places he visited while on leave in the Far East. In telling of his Utah service, he discusses the ship's role in enhancing fleet antiaircraft gunnery as World War II approached.

The focus of nearly all of this second volume of Admiral Eller's oral history is World War II. He began with a tour of duty as an observer with the Royal Navy, including service on board the battlecruiser HMS Hood and battleship HMS Prince of Wales before they fought the German battleship Bismarck. When hostilities began for the United States he was gunnery officer of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) and was on board when she was torpedoed. In the spring of 1942 he reported to the Pacific Fleet staff of Admiral Chester and served there throughout much of the rest of the war, working mostly in the gunnery section. He was both eyewitness and participant in a great deal of the planning and execution of the South Pacific and Central Pacific campaigns. Besides operating with Admiral Nimitz in Hawaii he made several trips to the forward area to see battle conditions firsthand. At war's end he commanded the attack transport USS Clay (APA-39). In the postwar period he had public information duty in San Francisco and then in the Navy Department in Washington.

The concluding portion of Admiral Eller's memoir provides convincing evidence of the versatility that is called for in a Navy unrestricted line officer. Among other things, Eller's skills included use of oral and written communication on behalf of the service, diplomatic and strategic ability in dealing with overseas nations, and seamanship and tactical ability on board ship. What also comes through repeatedly is Eller's proactive nature in getting things going—ranging from trips throughout the Middle East to kick-starting many worthwhile projects concerned with naval history.

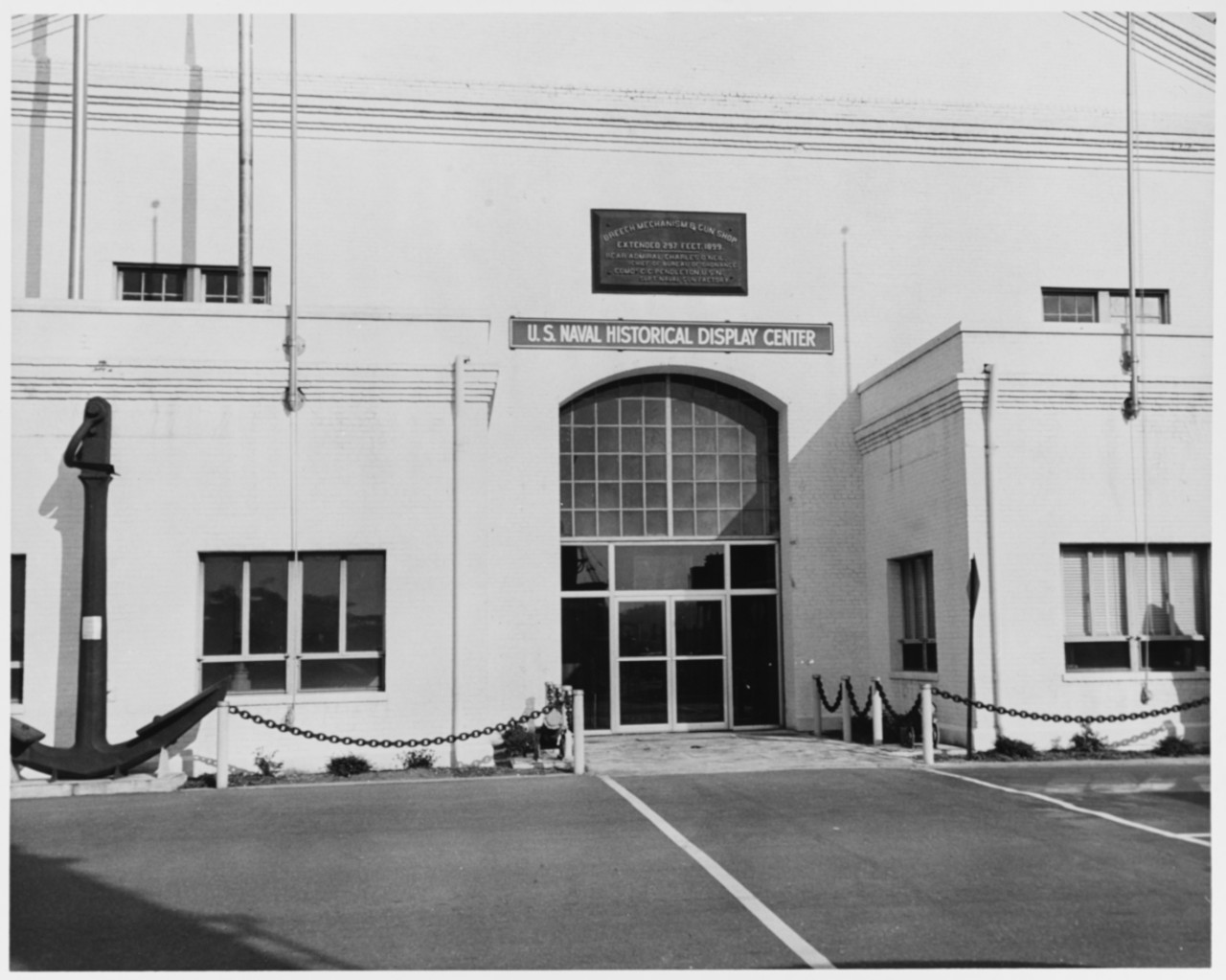

Perhaps Admiral Eller is best remembered today for his longtime leadership and stewardship as Director of Naval History and Curator in the Office of Chief of Naval Operations, a role he fulfilled from 1956 to 1970. "As the head of the Naval History Division, he was clearly energetic," observes Paul Stillwell in his preface to this final volume. Admiral Eller "not only served as honcho for a wide variety of projects, but also he raised funds and performed hands-on work in many cases of gathering materials, editing manuscripts, and providing answers to the many questions that came to his office. The Navy Museum in the Washington Navy Yard stands as a tangible legacy of Eller's stewardship."

Excerpt

Rear Admiral Eller: I wanted a museum in the Washington area from the start, and happily, two very fine gentlemen wanted it, too. One was Arleigh Burke, who was CNO when I came, and he kept pressing me to do something about it. We didn’t have men or money or location. Thomas Gates was Secretary of the Navy those first years; he was one of our finest secretaries.[1] I put Forrestal first, then Gates, and then our present one. Those in between varied in quality.

Paul Stillwell: I’d say you certainly had a leg up with two individuals like Burke and Secretary Gates supporting your efforts.

Rear Admiral Eller: Yes. Not only did Arleigh Burke support it, he pushed it. He kept pushing me. First, he talked of getting the Constellation from Baltimore, which of course we couldn’t; then of an active ship. One is finally in the yard, but not for what he wanted a big ceremonial ship with a good display area. He went to Europe in ’59 on an official visit, so I asked his aide, Commander Ray Peet, to put Greenwich and the Swedish naval museum on his agenda, and any other large maritime museum.[2] When he came back, Arleigh was all the more fired up. He said, “Let’s start a museum.” This kept going on. Finally, one day when Ray called up and talked about it again, I said, “Ask him to give me a memo that we need to start a museum.” That afternoon it came over by hand, just a memo, not a formal directive that provided men and money; however it gave me a lever of sorts.

We set up a committee from different offices in Naval Operations, in BuShips, and others that were involved. I acted as the chairman. Of course, the chairman always does the work, but usually gets what he wants. At that time, fortuitously, the Naval Gun Factory was being phased out. Buildings were being allocated to different departments of the government as well as to the Navy. We prepared a communication to the Secretary asking for one of the buildings. Actually, in order to be sure we got the right choice, we said, “We have this proposal to start a museum. Here are the possibilities.” And we named the old Naval Observatory— then occupied by BuMed—and other sites that would require expensive construction, and last the Navy Yard.[3] We specified that we needed a large building with ample storage and display area. We couldn’t call it a museum at the time because the Smithsonian was then building the big new armed forces museum and many objections would be, “Why do you need that? They’re going to have a very fine naval display,” as they do have, which we helped Mendel Peterson with—he was in charge there. You may know him.

Paul Stillwell: No, I don’t.

Rear Admiral Eller: He was a naval reservist who did reserve duties with us in our curator shop and was a great help.

We wanted the display space first of all to help build esprit in the Navy through visible evidence of its achievements, so we called it the Naval Historical Display Center. We hoped it would instruct and inspire.

Secretary Milne, Assistant Secretary for Material, buildings, etc., would make the decision.[4] We learned he was descended from a midshipman who had served with Nelson in the Battle of Trafalgar.[5] We happened to have a very fine painting of Trafalgar hanging in one of the offices in the Pentagon, and we had some good paintings in Milne’s office, loaned from the foundation or from the academy. So, we swapped the painting of Trafalgar one day when he was out of his office.

Meanwhile to avoid long delay we carried the rough of our request by hand to the different people who would have to initial it, such as JAG, Supply, comptroller, etc. Incorporating their modifications (which were never large, but enough to make them want to initial the final pager). Putting it in smooth, we pushed it through for initialing in a very short time. Then I went to see Secretary Milne, talked to him for about an hour. He wouldn’t agree yes or no at the time, but we got the building. We had the building—now to get people and money.

Paul Stillwell: Was it a building you had specifically asked for, or had you—

Rear Admiral Eller: We didn’t ask for the building since individuals wanting other sites might have blocked it. The request listed pros and cons for each. The building we wanted had fewest cons. Also, the commandant of the yard, Rear Admiral W. K. Mendenhall Jr., endorsed our request strongly, favoring the building we wanted, the one we have now. This is the finest building possible, just like an 18th century one with flying buttresses. In fact, it goes back to the early part of the 19th century. After we got it, BuPers sent me the first commanding officer. The receiving station provided working parties who cleaned it up and we started in.

[1] Thomas S. Gates Jr., served as Secretary of the Navy from 1 April 1957 to 7 June 1959.

[2] Commander Raymond E. Peet, USN, served as aide to Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burke from 1957 to 1959. The oral history of Peet, who retired as a vice admiral, is in the Naval Institute collection.

[3] BuMed - Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

[4] Cecil P. Milne served 1957 to 1959 as Assistant Secretary of the Navy (Installations and Logistics).

[5] Lord Horatio Viscount Nelson (1758-1805), British naval hero of the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, 1797, Battle of the Nile, 1798, Trafalgar, 1805.

(Note: Due to edits, corrections, and/or amendments to the original transcription draft, there are some inconsistencies between the recording and the text.)

Volume I

Based on five interviews conducted by John T. Mason, Jr., from November 1972 through July 1974. The volume contains 375 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1986 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has placed no restrictions on its use.

Volume II

Based on seven interviews conducted by John T. Mason, Jr., from December 1974 through August 1978. The volume contains 456 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1990 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has placed no restrictions on its use.

Volume III

Based on seven interviews conducted by John T. Mason Jr. and Paul Stillwell from December 1978 through December 1984, the volume contains 286 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 2018 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use.