Frankel, Samuel B., Rear Adm., USN (Ret.)

(1905–1996)

In the early part of his career Frankel served in the USS Trenton (CL-11) Augusta (CA-31), Chester (CA-27), and Chaumont (AP-5). Following this sea duty, he was Russian language student in Riga, Latvia, 1936-1938. He then served in the USS Ellet (DD-398) as gunnery officer and XO. He was Assistant Naval Attaché, Moscow, and Assistant Naval Attaché for Air, Murmansk-Archangel – service in connection with Lend-Lease shipments to the Soviet Union, directing repairs to U.S. vessels, salvaging stranded and abandoned vessels, and supervising hospitalization and repatriation of survivors. He served on the staff of CinCPac and as officer in charge, Joint Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Area; Assistant Chief of Staff, CinCPac; Deputy Director for Security, ONI; Deputy Director, Naval Intelligence; and Chief of Staff, DIA, from 1961 until his retirement in 1964.

Interview

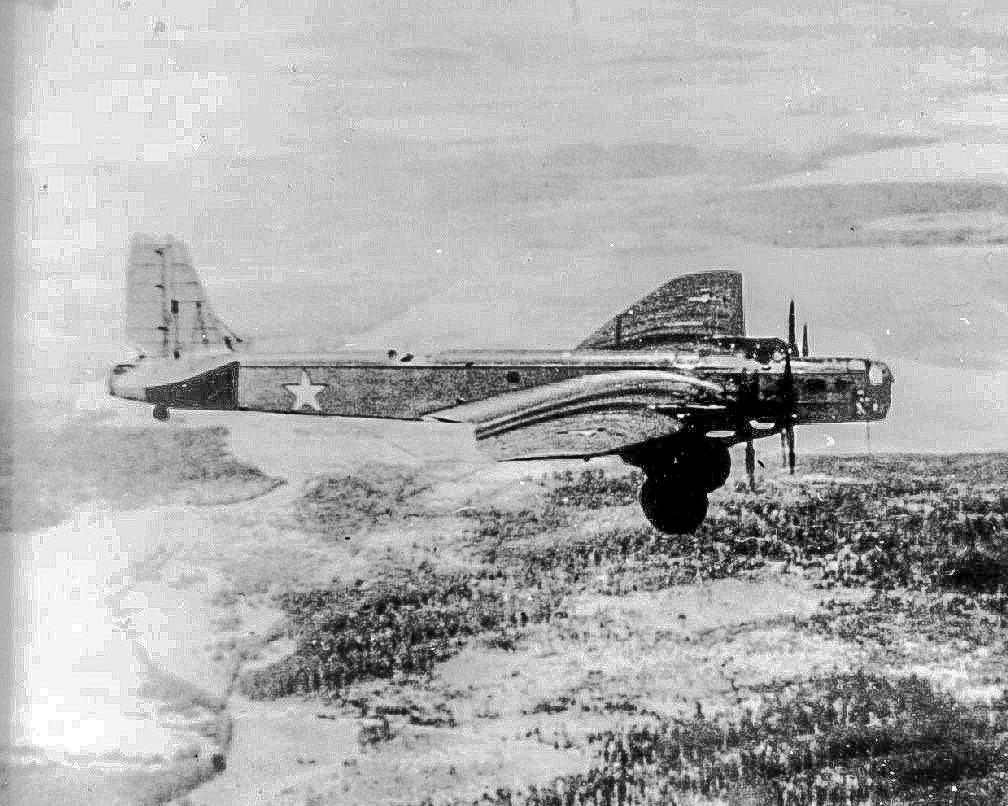

In this selection from his third interview with Dr. John T. Mason Jr. at the Mendota Apartments in Washington D.C., on 2 September 1970, Admiral Frankel recounts a harrowing tale shortly after the U.S. entry into World War II. Ordered to report to the embassy in Moscow from the city of Kuybyshev, Frankel tells of his fateful flight -- and crash -- in a Tupolev TB-3 in the frigid Russian winter.

Admiral Frankel: I started getting cold. I got colder and colder. Pretty soon I was getting a little bit numb, because it was open to the wind. The gunnery hatch was up there.

We could see that we were flying in fog. During the war they would fly low, in case there were any guns looking for Germans they wouldn’t have chance to hit these things. And too so they could actually navigate. They had to do sight navigation, there were no aides. to navigation, So the pilot was following along the railroad. We could see that there was fog. You couldn’t see anything except fog.

We came out of the fog. He went crossing back and forth to find the railroad, because he was really following the railroad, He’d lost it because of the fog

The things began to happen. We came to a station. The ceiling was very, very low and he started to circle this station with this big slow airplane. There was a patch of fog. As we came out of it, there was a parked freight train right there, I had time to think, maybe I did say, "Hold your hats boys." And we hit this train at the station.

There was a lot of commotion of course. I could feel myself being thrown around, blinded by snow coming in my face. Suddenly everything was very quiet. I said, "I guess I’ve had it. I must be wherever I’ve gone,” Then I could hear some noises and I started to stir, I realized I was all right.

These two fellows, Britishers, were in front with me. I said, "Are you all right?" They said, "Yes," I saw one of them was bleeding about the face and he said to me, "You've got blood on your face,” I said, "let's get out of here.”

I was so stiff and cold I had an awful time getting out. I felt nothing. We got out of the airplane.

There were the local gentry around, one of them with a pitchfork in true partisan style. The Russian passengers there, including a General, but they were all dressed like Russians in winter garb, no distinguishing marks. There I was. I recovered my cap and put it on my head, and there was this eagle. The General said in Russian, "We're your own people.” The fellow with the pitchfork said, "Maybe so, but you'll need documents,” looking at my cap. We found out later what they thought.

To reconstruct it: the pilot said that he came out of the fog and knew he was too low; he knew he couldn't pull out of it, this airplane had fixed landing gear, so it was no question of putting out wheels or anything. In reconstruction, apparently we hit the train with our landing gear. We knocked over a freight car filled with pipe. There was a lot of snow, this was what saved us. He sheared a wing off a telegraph pole and we started spinning. Though we did hit nose first, we spun around and continued tail first for a couple hundred yards through this deep snow, and finally came to rest. The pilot said he cut off his ignition as soon as he knew he wasn’t going to make it, so there was no fire.

Then the local gentry came out. They thought a German plane had come over dropped a bomb, and from our low altitude the blast had knocked the plane down.

So we scrambled around and picked up all seventeen pieces of baggage, including the one containing the Grand Manier which was still intact. We were taken thou to the station. The name of the town was Soombukhova. I’ll always remember that name, which probably has a meaning. It was warm there; they had a potbellied stove going. They gave us some borsch.

I started to feel little bits of discomfort. Meantime they had sent for a doctor, because of the cuts about the face and so forth. He came in, I don’t know whether he was a real doctor or not. But he immediately took out-his so-called white Jacket. I think he probably was a vet, because there was lots of blood all over him. He made me strip. In taking things off, they were sticking to my body. What had happened apparently: I was sitting right in line with the propellers and they were wooden propellers. When we hit, they shattered and some of the pieces came in the side of the plane and hit me. They were somewhat slowed down by the passage through the snow and through the side of the plane, but actually cut into my clothes and into my skin. They did a little damage, but not appreciably. I had some cuts on my back and on my leg on the left side. It must have been from the propeller blades. He proceeded to put bandages on me and fix me up. They weren't put on very well, especially on my leg. As soon, as I stood up, they fell down. But they were all superficial things, nothing serious.

Dr. Mason: The Britishers were in a similar condition?

Admiral Frankel: No. One had a nose bleed, but not a broken nose. Nobody else was hurt. I wasn't really hurt. I might have been, but I wasn’t.

Stuff was strewn all over. All those things were recovered and brought in there. The packing cases were patched up.

My concern, of course was that the Embassy in Moscow should be informed that we were all right, and that we would be along. They said they would take care of that.

A hospital train came along and we got aboard the hospital train. We mere well taken care of, we were fed, and given a plane-to sleep.

When we got into Moscow, they offered me a truck to carry my stuff to the Embassy. It was all very well done.

When I arrived, they were having lunch at the Ambassador’s residence where he lived at that time, Spasso House. I walked in there, expected to be welcomed like a conquering hero returned from the grave and he said, “What are doing here?” He didn’t even know that I was on my way there.

About this Volume

Based on ten interviews conducted by John T. Mason Jr. from August 1970 through April 1971, the volume contains 478 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1972 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee has placed no restrictions on its use.