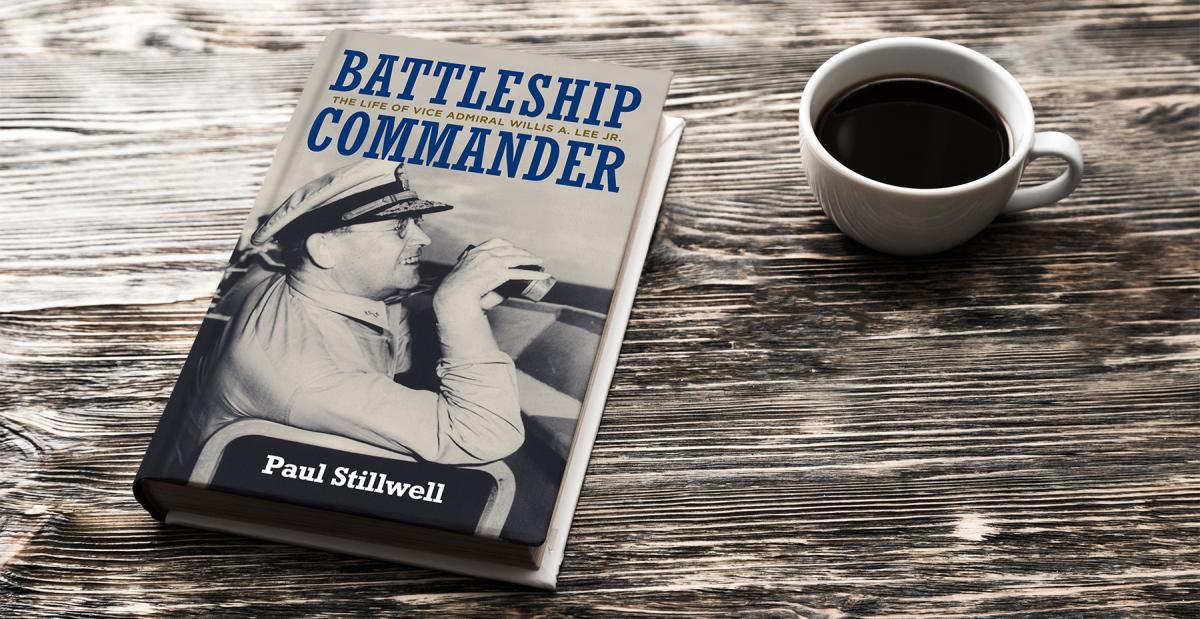

With his newly published biography of World War II naval legend Willis Lee, historian (and first-ever Naval History editor-in-chief) Paul Stillwell has served up the most in-depth portrait of Lee ever published. In this q&a, the author takes us behind the scenes of how this highly anticipated book came into being.

Now that your biography of Willis Lee is between covers, what made the book so difficult to finish?

As a bit of background, the inspiration for the biography stemmed from my service in the crew of the battleship New Jersey [BB-62] in 1969. While looking through a World War II cruise book on board ship, I came across a page that featured photos of the four flag officers who had been embarked during World War II. Lee was among them, and his name was completely new to me. His picture piqued my curiosity, and I began reading about him in other books.

For the record, I began the book’s research in the autumn of 1975 after consulting with retired Vice Admiral Edwin B. Hooper, who was then Director of Naval History. He had been a valued shipmate of Willis Lee during World War II and encouraged my efforts. I began reaching out to those who had served with Lee. I conducted oral interviews and wrote dozens of letters. Many people recalled Lee fondly and were happy to help.

Among them were Guilliaem and Mary Aertsen in Pennsylvania. Guil was Lee’s flag lieutenant through much of the war and served with him on a daily basis. He was in a sense a surrogate son for the childless admiral. I learned of a previous biographer named Evan Smith, who in the early 1960s had corresponded with Lee’s contemporaries. Many recalled events from half a century earlier.

Smith died before writing much of the text. I went to visit his widow Kate in Kentucky. She had wondered what to do with her husband’s material. She got her answer when she received my letter and gladly turned the research over to me so that Evan Smith’s aim could be fulfilled. Also, I went to see Lee’s sisters-in-law and nephew in Illinois. Margaret Allen, the sister of Lee’s wife Mabelle, was the family scribe and provided dozens of handwritten pages of recollections. I also had access to many documents, including letters Lee wrote to his future wife shortly after World War I. Also included in the trove were letters he sent to her when he was overseas during the war. Lee’s nephew Don Siders was most generous in sharing material. The Naval Institute’s oral history collection was a valuable resource I also made plenty of trips to the National Archives and a few to the Bureau of Naval Personnel.

Then, in 1980, I received an opportunity from the Naval Institute to edit a book of first-person recollections related to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. So I put the Lee project aside for a while. More books followed in which I was author, coauthor, or editor. These included four on battleships, two on submarines, two on aircraft carriers, one on the D-Day invasion of Normandy, and two on African-American naval pioneers. The latter covered the first black officers in the Navy and the Navy’s first black admiral. During much of that period I also had a full-time job with the Naval Institute that included magazine editing and conducting oral histories. And I must admit that I indulged in quite a bit of procrastination over the years. I finally submitted the completed manuscript to the Naval Institute Press in the autumn of 2020. Staying home during COVID had focused my attention on finishing the project.

Any number of persons asked me, “What took you so long?’ My glib answer was, “Twelve other books intervened.” Our youngest son Jim once overheard me voice that reply, and in a mocking tone he observed, “Yeah, I just hate it when that happens.”

The fact that VADM Lee was such an avid and precise marksman in his own right seems to have informed the way he handled himself in his “no-nonsense” command roles. Would you say that assessment is accurate? How do you see that correlation?

Willis Lee was unquestionably a superb marksman. One boyhood friend described him as having an unlimited supply of ammunition and an unlimited enthusiasm for shooting it. As a midshipman, in 1907 he achieved the unprecedented feat of winning the national rifle and pistol championships not only in the same year but on the same day. He was later often the coach of the Navy Rifle Team. In the 1920 Olympic Games in Belgium, Lee earned eight medals for shooting. His interest in small arms also translated to an almost obsessive quest to improve the shooting of guns on board Navy ships—from 4-inch to 16-inch.

Lee compartmentalized his life. He was indeed no-nonsense about such things as gunnery, radar, and tactics. He disliked paperwork and found others to do it for him. When he had to chide people in terms of operations, he did so gently. He commanded the cruiser Concord [CL-10] in the late 1930s and was on the bridge when his officer of the deck was slow in turning to avoid the aircraft carrier Ranger [CV-4]. Captain Lee said to him, “Just remember, there is no rule of the road that gives you the right of way through another ship.”

He did tolerate nonsense in some of his dealings with juniors. He was inclined to be lax and forgiving in terms of punishment. He once walked through an illegal poker game on board ship, taking care not to step on money or cards before moving on. He gave no thought of imposing punishment.

Another of his characteristics was that he was prone to wear sloppy uniforms. Admiral Harold Stark once wrote in a fitness report said that Lee’s military appearance was “exceptional.” It was not a case of being exceptionally excellent; instead, Lee’s outfit was an exception to the high standards expected. Lee’s concern for enlisted shipmates was one of friendliness and support. His crews loved serving with him. Willis Lee was a walking example of the maxim that loyalty down begets loyalty up.

VADM Lee should be given some sort of non-military recognition for his ability to refer to his wife as “Chubby” or “Chub.” Was that connotation somehow different from what it is today?

No special awards are necessary in this regard. Mabelle’s nicknames originated in her family before she met her future husband, though it’s hard to understand why she was called “Chub” and “Chubby.” In one letter he wrote to her in 1919, he addressed her as “Wee small Child.” She stood about five feet tall. In another letter that year, while he was overseas, he wrote “It may be that distance lends enchantment to the stew but you look good to me from here—what there is of you—91 pounds 7 oz or thereabouts I guess.”

She habitually addressed him as “Lee.” In one telegram to her from Belgium, he signed it “Lovely.” In a subsequent letter he explained: “Did you get my cable? Now you know how much I love you. I ran the last two words together to save 16ct. However that was only because I didnt have any more money with me. Had a hard time convincing the man at the cable office that my name was Lovely—He said I didnt look like it to him.” Lee’s sense of humor was a constant attribute throughout his life, as was his apparent aversion to using apostrophes in contractions.

In your telling, VADM Lee endeared himself to the junior officers and crew who served under him, especially on board ships, and mostly for his quiet, hands-off approach to leadership. Did his fellow wartime leaders realize how effective that approach could be?

Perhaps some who had served with Lee modeled their approach on his. But much of naval leadership behavior had to do with individual personalities. The leadership styles of wartime leaders spanned the spectrum from driver/screamer to gentle/avuncular. Take the two principal numbered fleet commanders in the Pacific. Admiral William Halsey was brash, aggressive, impulsive, and enjoyed being lionized in the news media. Admiral Raymond Spruance was his virtual antithesis: quiet, cerebral, deliberate and reluctant to seek public acclaim.

Lee, incidentally, eschewed news media attention, considering it a distraction from his mission of fighting the war. He was even wary of noted historian Samuel Eliot Morison, who visited Lee’s flagship Washington [BB-56] in the spring of 1943. Only reluctantly did the admiral agree to an interview. In December 1942, in the wake of his victorious night surface gun battle against the Japanese, Lee’s “Dear Chubby” letter was a model of brevity. One paragraph said, “I miss you and am sorry I wont be able to see you Christmas. Don’t let newspaper stories worry you. I will take good care of me.” He did absolutely no blowing of his own horn.

The title of the book is appropriate, but the book itself also details Lee’s command of many more ship-types than battleships and the key roles he played in making them more efficient and accurate in combat. In reading the book, one quote stands out that could have been appropriate for the title. On page 138, describing his letters to the Bureau of Ordnance, they were “all kinds of things about guns.” What do you think?

Lee was indeed concerned with the value of accurate gunnery. A particular emphasis of his was equipping the U.S. fleet with forests of antiaircraft guns, because it was clear from the war then being fought in Europe and from the effective Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that aviation had a prominent role in modern warfare. The key to making gunnery, both long-range and antiaircraft, effective was the use of fire control radar to guide guns onto targets. He was particularly enamored of a 5-inch projectile equipped with a proximity fuze. A tiny radio transmitter in the nose sent out signals when the projectile was near the target; the return signal detonated the warhead.

One of the men on Lee’s staff was James Van Allen, who later became famous as the discoverer of the Van Allen Radiation Belt. He delivered sample projectiles to Lee’s flagship Washington. Lee, who had a scientific mind and curiosity about mechanical objects, had a projectile cut open so he could observe the magic innards. Prior to the proximity fuze, explosion times were set in before firing, with the hope that the projectile and aircraft would arrive at the same place at the same time.

Lee also campaigned vigorously for the installation of radar on board warships. In fact, he was one of the few flag officers of his generation with a thorough understanding of radar’s capabilities. He put that knowledge to great use on 14–15 November 1942, during a desperate nighttime struggle against the Japanese for control of Guadalcanal. Lee had an ad hoc six-ship task force that comprised four destroyers and two battleships, his flagship Washington and the South Dakota [BB-57]. The mission of the Japanese surface force was to bombard the island in order to destroy property and undermine the morale of American servicemen. Japanese guns and torpedoes quickly put the destroyers out of action. The South Dakota was rendered ineffective by a temporary power failure and suffered grievously from hits by Japanese guns.

Lee was a pioneer in establishing the concept of combat information centers to correlate and pass on information from radars. That night he stood on the starboard side of the Washington’s bridge as large-caliber projectiles hurtled through the air in what one observer described as a “red snowball fight.” Lee, who had poor vision ever since a boyhood accident, was temporarily blinded when the Washington’s initial salvo blew his glasses to the deck. He groped with his hands before recovering them. The flagship’s big guns, directed by radar, scored damaging hits. They were so effective that the Japanese flagship Kirishima sank within a few hours. Research contributed by many men who were there that night sketched a portrait of the combination of noise, blast effect, and bright lights. The superstructure of the South Dakota was riddled with holes. The ship did not show interior lights, so crew members had to feel for their dismembered shipmates in darkness. The effectiveness of the Washington’s big guns that night prevented the planned bombardment of Guadalcanal. It was a turning point in the struggle for the island and put U.S. naval forces on the long path ahead toward eventual victory.

If one were to make a movie about VADM Lee’s wartime leadership, among all the strong personalities of the Nimitzes, Halseys, and Kings, who would be a good candidate to play the low-key leader that Lee was?

The default answer is, of course, Tom Hanks, who was masterful in military roles in such films as Saving Private Ryan, Apollo 13, and Greyhound. Also good would be Ryan Reynolds, who has been in a number of action films and who notably portrayed attorney Randy Schoenberg in Woman in Gold. The film depicted the lawyer’s successful efforts to reclaim paintings that had been looted by Nazis in World War II.

As for the hypothetical movie, it might well produce a whirring sound from the Arlington National Cemetery—that of Willis Lee turning over in his grave.

Considering Lee’s understated and unorthodox but nonetheless effective command style, are any more lesser-known Willis Lees worthy of not-yet-written profiles or biographies?

The interesting phenomenon in this case is that it takes the right match between author and subject. My association with Lee’s life really came about as a matter of serendipity. There is no central authority that assigns authors to subjects. It takes a writer who develops a passion for the individual. Some years ago I encountered the daughter of Admiral Royal Ingersoll, who served as Commander in Chief Atlantic Fleet during World War II. She had her father’s papers and wondered how to line up someone to write about his life. My suggestion was that she donate the material to an archive so that it would be available if someone did come along to write his story.

Biographers have already written about a number of Navy leaders in the World War II era. Names that come to mind are William Leahy, Ernest King, Chester Nimitz, William Halsey, Raymond Spruance, Marc Mitscher, Eugene Fluckey, Slade Cutter, John S. McCain Sr., Thomas Kinkaid, Harold Stark, Ben Moreell, Frank Jack Fletcher, Richmond Kelly Turner, Jocko Clark, Thomas Hart, Clifton Sprague, John Towers, and John Thach.

Biographies are in the works for Arleigh Burke and Robert Ghormley. Suitable candidates for future books include Alan Kirk, William Blandy, Arthur Radford, Forrest Sherman, Frederick Sherman, Kent Hewitt, Jonas Ingram, Husband Kimmel, Francis Low, Charles Cooke, and Frederick Horne.

What’s next for Paul Stillwell?

A couple of items are on my list of possibilities. One is an updated edition of my 1986 book Battleship New Jersey: An Illustrated History. The ship was in commission for five more years after the book came out. She operated as the centerpiece of what was then known as a battleship battle group. She took part in national and international exercises in the Pacific and joined sister Missouri [BB-63] as the only two active battleships in that ocean. The New Jersey’s last skipper promoted a motivational motto, WETSU, “We eat this stuff up.” Rising costs for personnel spelled the end of her long career, and she was decommissioned in early 1991, unable to participate in Operation Desert Storm, then in progress. Subsequently the ship became a memorial/museum in Camden, New Jersey, where she welcomes visitors to this day.

Another option would be a history of the 1954 St. Louis Cardinals baseball team. This grows out of my early ambition to become a sportswriter. Happily I converted to naval history, but the old longings are still there. That year’s team marked a big step forward in the Cardinals’ history. Anheuser-Busch had bought the team the previous year, and 1954 was the year the Busch ownership really made its impact. The thrust was to use the ball club as a marketing tool for the brewery, and it was eminently successful in that regard. As part of the promotion effort, the 1954 Cardinals were the first big-league team to fly coast to coast. The ballpark was renovated to include some of baseball’s first luxury suites. After many years as a whites-only team, the Cardinals’ first African-American players made their debuts that year. Outfielder Wally Moon was voted as the National League’s Rookie of the Year in a season that also included future Hall of Famers Ernie Banks and Hank Aaron.