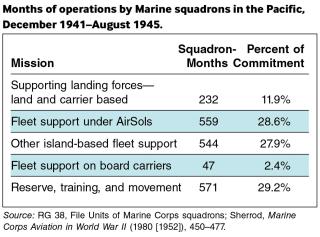

For the past century, the U.S. Marine Corps has declared that its aircraft exist to support Marines on the ground. But during the storied battles of the Pacific war from 1941 to 1945, the Corps’ squadrons primarily supported the fleet at sea, not the Corps’ landing forces ashore. In World War II, Marine aviation served as a land-based component of fleet aviation, fighting for air superiority and striking Japanese ships and bases to help the U.S. fleet achieve sea control. So how and why did Marine aviation in the Pacific only infrequently support Marines ashore—and more often supported the fleet instead?

Marine Aviation Doctrine in 1941

In 1939, Marine Colonel Roy S. Geiger, commanding officer of Aircraft One, stated, “The primary reason for the Marine Corps having airplanes is their close support of ground troops.”1 Geiger was not the first Marine to declare ground support as the primary role of Marine aviation. As early as 1919, Major Alfred A. Cunningham had testified before Congress that “the only excuse for aviation in any service is its usefulness in assisting the troops on the ground.”2

But such had not been the role of Marine aviation in World War I. Rather than directly supporting the American Expeditionary Forces, the First Marine Aviation Force had flown under the Royal Air Force’s Northern Bombing Group, striking targets such as railyards in the German rear. The 1st Marine Aeronautic Company had flown antisubmarine patrols from the Azores.3

Chastened by this experience, Cunningham, Geiger, and their fellow pioneers had toiled hard to realize a ground-support role for Marine aviation. In 1927 and 1928, two Marine squadrons supported Marines fighting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua with bombing and strafing attacks, reconnaissance, aerial resupply, and casualty evacuation. Marine aviators tested techniques in fleet exercises throughout the 1930s and captured their lessons in the Tentative Landing Operations Manual in 1935.4

By the eve of World War II, Marine Corps doctrine had explicitly established this ground-support role. A 1940 Marine Corps publication on aviation stated in its first paragraph:

The primary mission assigned to Marine Corps Aviation is to support the Fleet Marine Force in landing operations, and to support other troop activities in the field. Secondarily, Marine Corps Aviation serves as replacement squadrons for Naval carrier based aircraft.5

It is worth noting how naval doctrine conceived both Navy and Marine Corps aviation would “support the Fleet Marine Force in landing operations.” According to the Navy’s 1938 Landing Operations Doctrine, carrier-based (naval) aviation would support the landing force until landing force (Marine) aviation was established ashore. Aviation’s first job was to gain air superiority through a combination of fighter protection and strikes against enemy airfields.

During the landing and after, aviation would continue to protect troops, ships, and aircraft from enemy air attack, bomb and strafe enemy defenders, and conduct reconnaissance and spotting for artillery and naval gunfire. The Navy acknowledged that significant logistical challenges might require naval aviation to support the landing force until such challenges could be overcome.6

As World War II approached, the need to support a drive across the Central Pacific with island-based aircraft became increasingly evident, though not universally accepted. Marine planners such as Lieutenant Colonel Earl H. Ellis had considered the role and organization of aviation in amphibious operations as early as 1921.7 But throughout the 1930s, the limited range of land-based aircraft and the limited number of aircraft carriers confounded War Plan Orange planners.8

At the outset of the Pacific war, gaining air superiority before the assault was a job that planners expected carrier-based naval aviators to do; Marine aviators, as Geiger had stated, existed primarily to attack an island’s defenders.

Wartime Expansion

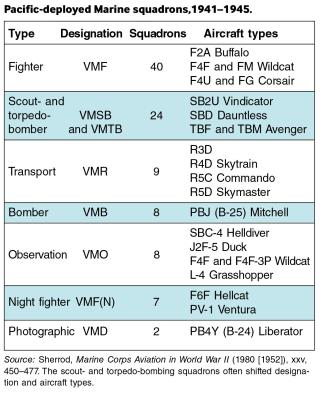

Marine aviation expanded from 13 squadrons on the eve of Pearl Harbor to 153 squadrons during the war. Ninety-eight squadrons deployed to the Pacific between December 1941 and August 1945.9

A helpful way to measure what Marine aviation did and did not do in the Pacific is to tabulate how each of these squadrons spent its months deployed. An examination of their monthly war diaries reveals some interesting points.

Island defense, 1941–42: As the U.S. Pacific Fleet recovered from the attacks on Pearl Harbor, it sought to hold onto outposts such as Wake and Midway Islands and established new bases on friendly islands along the sea lines of communication between the U.S. West Coast and Australia. From December 1941 to the end of 1943, 17 Marine fighter squadrons and scout and torpedo-bomber squadrons defended these islands for an aggregate of 113 months.

The three squadrons that fought at Wake Island and Midway faced off in violent actions against the Imperial Japanese Navy. The remaining squadrons fended off occasional reconnaissance and nuisance raids and spent countless days patrolling a vast, empty ocean.

While these squadrons were co-located with base defense battalions, to characterize the aviation mission as one of support to these ground forces would misrepresent its purpose. These Marine fighters and bombers operated under the local naval commander to protect the base from attacks and to detect Japanese naval activity.10

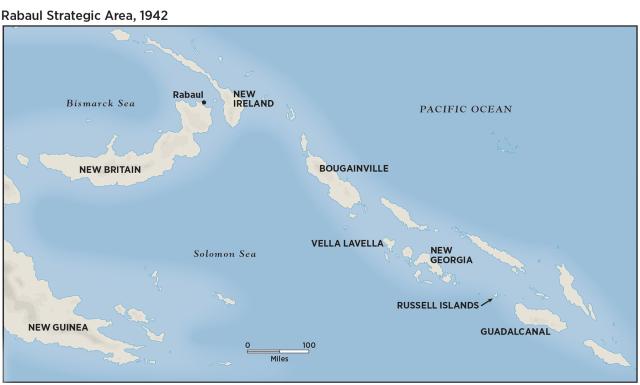

The Solomons, 1942–44: With the amphibious landing at Guadalcanal in August 1942, Marine aviation was thrust into its most sustained and most important contribution to the Pacific war. The Solomons campaign drew just over 30 percent of the Marine aviation commitment to the Pacific war. From August 1942 to late 1944, more than half the Marine squadrons that deployed to the Pacific operated in the Solomon Islands for at least three months.11

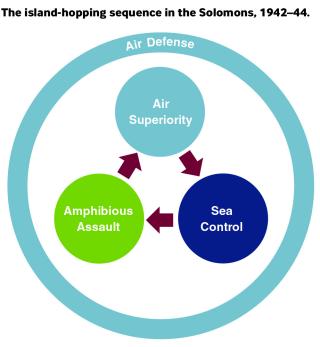

It is helpful to conceive of the Solomons campaign in sequential phases:

From August 1942 to February 1943, U.S. forces fought a series of desperate air, sea, and land actions to seize and hold Guadalcanal and its vital airstrip, Henderson Field. From February to May 1943, Japanese and U.S. air and naval forces skirmished in many minor and a few major actions, and a U.S. amphibious force seized the Russell Islands in an unopposed landing.

From June to August, an Army and Marine Corps landing force fought a brutal struggle to secure New Georgia in the central Solomons, while air forces and naval task groups protected the amphibious assault ships. Supported by Marine aircraft operating from New Georgia, a U.S. amphibious force then seized the lightly defended island of Vella Lavella.

A final amphibious leap in December to Bougainville, deep into Japanese territory, obtained airfields within range of Rabaul. U.S. and Australian aircraft operating from the northern Solomons, New Guinea, and fast carrier task forces wrested control of the air over Rabaul and neutralized its use as Japanese base.12

The role Marine aviation filled during this campaign is as complex as it is substantial. It would be misleading to argue that Marine aviation provided no support to Marine and Army landing forces in the Solomon Islands. But that support was rarely provided directly to ground forces; rather, Marine aviation operated as part of a joint, combined air force, known as the Cactus Air Force in 1942 and formally established as Air Solomons, or AirSols, in early 1943. Though a joint air force, AirSols was a subordinate element of the South Pacific Area, a naval command under Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley until October 1942 and Admiral William F. Halsey until 1944.13

AirSols achieved air superiority, which cleared the way for the fleet to gain sea control, which made landing operations possible. Landing forces seized islands on which to build airfields, and the process continued up the island chain. Throughout the campaign, fighter squadrons provided air defense for ships, airfields, and troops ashore.

From August 1942 until ground fighting on Guadalcanal ended in February 1943, Marine fighter squadrons fought off Japanese aerial onslaughts against the indispensable airfield on Guadalcanal, naval vessels offshore, and the 1st Marine Division and its attachments. While Marine aces chalked up victories and fame in historic dogfights, Marine scout- and torpedo-bomber squadrons attacked Japanese ships running the Slot (the channel running the length of the Solomons between the parallel island chains) to reinforce the Japanese defenders.14

Marine squadrons continued to combat Japanese aircraft and strike Japanese airfields and vessels throughout the Solomons campaign. Importantly, Marine aircraft began flying close-support missions for the landing force at New Georgia. During July and August 1943, Marine Corps, Army, and Navy flyers flew 37 air-support missions at New Georgia. While these missions achieved limited success due to the difficulty of acquiring targets in the jungle and the infancy of coordination procedures, Marines applied the experience gained on New Georgia at Bougainville in December. There, five torpedo-bomber squadrons flew seven smaller missions, achieving greater effect.15

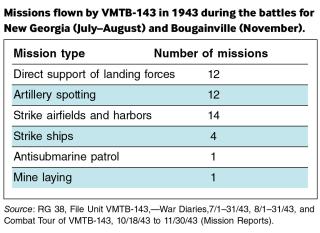

Even while Marine squadrons flew ground-support missions, they continued to strike against other targets. The war diary of Marine Scout Bomber Squadron (VMTB) 143 is instructive. This Avenger squadron flew missions in direct support of the landing forces on both New Georgia and Bougainville, and often detailed an aircraft to spot for landing force artillery. As the table below indicates, even during the height of ground combat on these islands, the squadron continued to strike Japanese airfields, harbors, supply depots, and vessels; patrol for submarines; and lay mines.

This torpedo-bomber squadron, and a dozen other scout- and torpedo-bomber squadrons, directly supported landing forces ashore in the central and northern Solomons. Their contribution, though important, represents a small fraction of the Corps’ aviation commitment to the Solomons campaign—less than 2 percent when measured in squadron-months.16

Marine aviation’s contribution to the Solomons campaign was considerable, but it was in winning the battle for air superiority—not in directly supporting the fight on the ground. Twenty-seven Marine fighter squadrons flew in the Solomons, and 74 Marine aviators became aces.17 By the time Allied forces had neutralized Rabaul in early 1944, Allied aviators had broken the back of Japanese naval aviation.18 Marine fighter squadrons had comprised a quarter of AirSols’ fighter strength and claimed a disproportionate share of AirSols’ air-to-air victories.19 In the final weeks of the campaign, Marine scout- and torpedo-bombers flew more than half of the Allied strikes against Rabaul. With the island fortress encircled by Allied airfields, the Japanese withdrew their remaining air power from Rabaul in late February 1944.20

The Central Pacific, 1943–44: Before the Solomons campaign had concluded, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz had begun the Pacific Fleet’s drive across the Central Pacific. Army and Marine Corps landing forces conducted amphibious assaults in the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana islands. In each, the landing forces benefited from direct air support—but not by Marine aircraft. Only long-range Army bombers and carrier-based aircraft could reach these islands. While Marines battled, burned, and blasted Japanese defenders out of their fortifications, no Marine aviators bombed or strafed in front of them. Marine aviation was limited to artillery spotting by tiny L-4 Grasshoppers and, once airfields opened, medical evacuation by transport squadrons.21

Marine squadrons flew in the Central Pacific out of the spotlight. Once islands had been secured and the fleet had moved west, Marine fighter, scout-, and torpedo-bomber squadrons moved in. In a period that historian Robert Sherrod labeled “The Doldrums,” Marine aviation sat out most of 1944. Twenty-seven squadrons, comprising 14 percent of the Corps’ aviation commitment during the Pacific war, patrolled the Central Pacific month after month, occasionally striking isolated Japanese bases on islands the war had bypassed.22

The Western Pacific, 1944–45: Distances in the Southwest Pacific presented an opportunity for Marines to get back into the direct support mission. While the 1st Marine Division faced fierce resistance as it assaulted the coral ridges of Peleliu in September 1944, a single Marine Corsair squadron arrived and immediately began close support missions from the captured airfield. Around this time, Far Eastern Air Forces ordered 1st Marine Air Wing to provide seven scout-bomber squadrons to the Leyte amphibious operation.

By the end of the war, 11 fighter squadrons, seven scout-bombing squadrons, two night-fighter squadrons, one bombing squadron, and a transport squadron had supported General Douglas MacArthur’s army in the Philippines, providing direct support and protection from aerial attacks—nearly 6 percent of the corps’ aviation commitment to the Pacific.23

While Marine squadrons had languished in the Central Pacific in 1944, the Japanese were relying increasingly on suicide attacks against ships to compensate for their inferiority in the air. To defeat this threat, the Navy increased the fighter strength on board its carriers and sought to leverage the Corsair’s superior fighting ability. Marines had Corsairs, and Marine squadrons were available.

By early 1945, eight Marine fighter squadrons had qualified for carrier operations and deployed aboard four of the new Essex-class carriers. These eight squadrons defended Task Force 58 from suicide attacks, raided the Japanese Home Islands and Indochina, and flew in direct support of the landing forces at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.24 Another nine squadrons deployed aboard escort carriers in 1945, four of which saw combat in the Philippines and Okinawa.25

Marine air support on Iwo Jima was brief, but violent. Task Force 58’s eight Marine fighter squadrons flew rocket and strafing attacks against island defenders and combat air patrol over the fleet for four days before departing on D+3, leaving support to the three Marine divisions for the rest of the five-week battle to Navy escort carrier squadrons and, eventually, Army P-51 Mustangs.26 In contrast, Okinawa saw the realization of Marine Corps doctrinal aspirations regarding aviation. Thirty-four Marine squadrons contributed to the operation for at least one month, flying close support and artillery observation missions and defending the fleet from suicide planes.27

Landing-Force Support vs. Fleet Support

Marine aviation had directly supported Marine assault forces in just half of the Corps’ Pacific landings. Of the service’s 12 major amphibious operations, Marine aviation had directly supported the landing force in just five (New Georgia, Bougainville, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa) and had attacked ships and airfields while providing fighter protection in a sixth (Guadalcanal). In only one of these operations—Okinawa—could such direct support be characterized as a significant force multiplier.

Marine aviation at Tarawa, Cape Gloucester, Roi-Namur, Saipan, Guam, and Tinian had been limited to reconnaissance and transportation. Support to MacArthur’s army in the Philippines had constituted a significant contribution by Marine aviation, one that was repeatedly lauded by Army commanders. However, in the eight other major landings conducted by U.S. Army and Australian divisions in the Pacific, Marine aviation had provided no direct support to the landing forces.28

An obvious question this raises is what nearly 100 Marine squadrons did besides directly supporting landing forces. The table on the following page discloses how the Corps’ squadrons spent their months in the Pacific.

Support to the landing forces represented just 12 percent of Marine aviation’s commitment to the war effort in the Pacific. And this accounting is generous; any month in which a squadron directly supported a landing force, even for one mission, is categorized here as “supporting landing forces” and not under another category. As the experience of squadrons such as VMTB-143 suggests, the percentage of overall missions Marines flew in support of landing forces versus those they flew in support of the fleet was even lower.

The short answer to why Marine aviation supported the fleet far more than it supported landing forces is that the Corps had been equipped with carrier aircraft but had no carriers from which to fly them. Distances in the Central Pacific precluded support from other islands by short-legged Marine aircraft.

While the fleet could hardly have spared carrier deck space for Marine aircraft in 1942 and 1943, that had not been so true in 1944. At the time of the Tarawa assault in November 1943, the Pacific Fleet had 22 light and escort carriers; by the Marianas landings in June 1944, it had 55 of these small carriers.29 Under wartime pressure to qualify naval aviators on board carriers and get Marine aviators into combat, the Navy and Marine Corps had suspended carrier training for Marines. In 1944 the Corps had carrier aircraft, and the Navy had carriers, but the Marines did not have many qualified carrier pilots. Instead, Navy pilots flying from these small carriers directly supported the amphibious assaults in the Central Pacific, with less than desired results.30

The Value of Versatility

But that is not the whole story. Marine aviation operated extensively in the South Pacific, yet still rarely flew in direct support of ground troops. The Corps had not been as ready as it had presumed to support its Marines ashore. Until the Corps had developed effective coordination methods and control units, attacking targets on jungle islands proved immensely difficult. Instead, the Cactus Air Force and AirSols employed Marine aviation in roles for which it had been well suited: in air-to-air combat and strikes. Flying from mud and coral airfields threatened by enemy air, naval, and occasional ground attacks, Marine fighter pilots had eroded Japanese air strength while Marine bomber pilots had struck Japanese airfields and ships.

Command arrangements had exacerbated the Marine Corps’ difficulties employing its squadrons in support its divisions. Until October 1944, the Corps’ senior aviation command, Marine Air Wings Pacific, did not fall under the Fleet Marine Force, but under Nimitz’s Air Pacific command. While subordinating Marine Air Wings Pacific to the Fleet Marine Force in 1942 would not have surmounted all the obstacles that kept Marine squadrons from flying off carriers and providing close air support, this separation between Marine aviation and landing forces undoubtedly aggravated the difficulties the Corps faced realizing its doctrinal aspirations.31

One may conclude from this that Marine aviation was misemployed during the Pacific war. A more relevant conclusion may be that aviation’s versatility can be one of its more valuable attributes. World War II Marine aviation was not a one-trick pony, but a flexible tool that naval commanders employed to meet the needs of the moment. With aircraft that could operate inside contested airspace from austere airfields and hit targets ashore, at sea, and aloft, Marine aviation was the right tool for the tough job in the Solomons.

Today, retired generals and defense analysts urge caution as the Marine Corps divests major elements of the air-ground team that has served the nation well since 1950.32 In his 2018 Planning Guidance, General David Berger reminded his Marines that “During World War II, we as a Service, clearly understood that Marines operated in support of the Navy’s sea control mission.”33 As the Corps refocuses on supporting the fleet in great-power competition and conflict, understanding Marine aviation’s historic role as a land-based, fleet air component may provide instructive lessons.

1. Col Roger Willock, USMCR, Unaccustomed to Fear: A Biography of the Late General Roy S. Geiger, U.S.M.C. (Quantico, VA: Marine Corps Association, 1983), 181.

2. Maj Alfred A. Cunningham, USMC, “Value of Aviation to the Marine Corps,” Marine Corps Gazette, September 1920, 222.

3. LtCol Edward C. Johnson, USMC, Marine Aviation: The Early Years, 1912–1940 (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 1977), 13–25.

4. Johnson, Marine Aviation, 55–57, 65.

5. U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Corps Aviation General (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1940), 3; Robert Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 2nd ed. (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1980 [1952]), 31–32; and Col Allan Reed Millett, USMCR (Ret.), Semper Fidelis: The History of the United States Marine Corps (New York: Macmillan, 1980), 334.

6. U.S. Navy, Landing Operations Doctrine, 1938 (F.T.P. 167) (Washington, DC: Office of Naval Operations, Division of Fleet Training, 1938), 151–58.

7. LtCol Earl H. Ellis, USMC, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia (Operation Plan 712), reprinted as FMFRP 12-46 (Washington, DC: U.S. Marine Corps, 1992 [1921]), 67.

8. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 184, 191, 194–202.

9. Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 33, 435, 450–77.

10. Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1875–2006, Record Group (RG) 38, Series: World War II War Diaries, Other Operational Records and Histories, ca. 1/1/1942–ca. 6/1/1946, File Units of Marine Corps squadrons, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, MD; Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 4: Coral Sea, Midway, and Submarine Actions: May 1942–August 1942 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1949), 73, 86, 104–5, 110–11, 137, 145, 263; and Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 34–64, 450–77.

11. File Units of Marine Corps squadrons, RG 38, NARA; Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 450–77.

12. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 6: Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 22 July 1942–1 May 1944 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1959); Henry I. Shaw, Verle E. Ludwig, and Frank O. Hough, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II: Isolation of Rabaul, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958).

13. U.S. Army Center of Military History, “World War II—Asiatic-Pacific Theater Campaigns.”

14. File Units of Marine Corps squadrons, RG 38, NARA; Henry I. Shaw, Verle E. Ludwig, and Frank O. Hough, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II: Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 235–374; Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 450–77.

15. Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 150–52, 189–92.

16. File Units of Marine Corps squadrons, RG 38, NARA; Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 450–77.

17. CDR Peter B. Mersky, USNR, Time of the Aces: Marine Pilots in the Solomons, 1942–1944 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1993), 39.

18. U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (USBS), Naval Analysis Division, The Allied Campaign Against Rabaul (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1 September 1946), 24.

19. Shaw, Ludwig, and Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 477.

20. Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 392–405; Shaw, Ludwig, and Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 537; and USBS, Allied Campaign Against Rabaul, 24–25.

21. Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 33, 435, 450–77; Henry I. Shaw, Verle E. Ludwig, Frank O. Hough, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II.: Central Pacific Drive, vol. 3 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958).

22. Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 237–61, 450–77.

23. George W. Garand and Truman R. Strobridge, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II: Western Pacific Operations, vol. 4 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1971), 211–12, 226–28, 316, 323–33, 339–47; Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 450–77.

24. Gen Vernon E. Megee, USMC, (Ret.), “The Evolution of Marine Aviation,” Marine Corps Gazette, September 1965, 46; MajGen John P. Condon, USMC, (Ret.), Corsairs and Flattops (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 4–5, 38–42, 51–86.

25. Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 450–77.

26. Condon, Corsairs and Flattops, 36–39.

27. Megee, “Evolution of Marine Aviation,” 46; Gen Vernon E. Megee, USMC, (Ret.), oral history transcript (Washington, DC: Historical Division, U.S. Marine Corps, 1973), 2–24.

28. Samuel Milner, Victory in Papua (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1957); George L. MacGarrigle, US Army Campaigns of World War II: Aleutian Islands (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1992); Shaw, Ludwig, and Hough, Central Pacific Drive, 117–230; and Robert Ross Smith, The Approach to the Philippines (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History,

29. Kent G. Budge, “Independence Class, U.S. Light Carriers” and “Escort Carriers,” Pacific War Online Encyclopedia, pwencycl.kgbudge.com/I/n/Independence_class.htm.

30. Sherrod, History of U.S. Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, 325–27; Gen Alexander A. Vandegrift, USMC (Ret.), Once a Marine: The Memoirs of General A. A. Vandegrift (New York: Norton, 1964), 246–47; Megee, oral history transcript, 2–11.

31. Garand and Strobridge, Western Pacific Operations, 44–47.

32. See James Webb, “Momentous Changes in the U.S. Marine Corps’ Force Organization Deserve Debate,” The Wall Street Journal, 25 March 2022; Gen Terry Dake, USMC (Ret.), “The Marine Corps’ Reorganization Plan Will Cripple Its Aviation Capabilities,” Task and Purpose, 22 April 2022; LtGen Paul K. Van Riper, USMC (Ret.), “The Marine Corps’ Plan to Redesign the Force Will Only End Up Breaking It,” Task and Purpose, 20 April 2022; Gen Anthony Zinni, USMC (Ret.), “What Is the Role of the Marine Corps in Today’s Global Security Environment?” Task and Purpose, 19 April 2022; and Col Mark F. Cancian, USMCR (Ret.), “The Marine Corps’ Radical Shift toward China,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 25 March 2020.

33. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, 38th Commandant’s Planning Guidance (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 2019), 4.