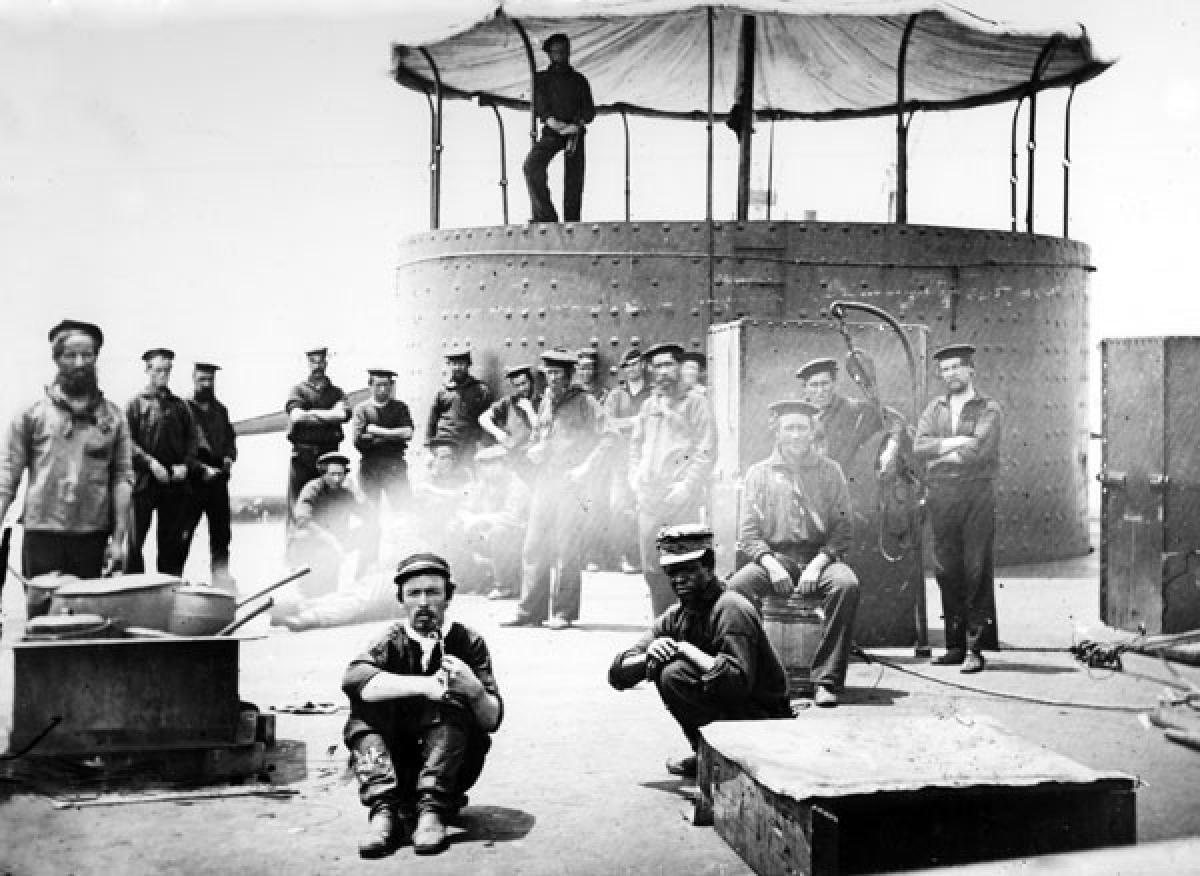

Referring to themselves as “the Monitor Boys,” the men of the U.S. Navy's first ironclad experienced storms, battles, boredom, poor living conditions, and disaster as they participated in the transformation of naval warfare.

Once the Monitor was launched on 30 January 1862, her commander, Lieutenant John L. Worden, had to quickly secure a crew. He estimated that he would need 10 officers and 47 men to manage the ship. Besides Worden, the complement of officers when she set out for Hampton Roads consisted of four engineers, one medical officer, one paymaster, two masters, and one executive officer.

The enlisted men were all volunteers. Since the ironclad was such a revolutionary warship and different from any other vessel in the U.S. Navy, Worden did not wish to accept men just arbitrarily assigned to her. Instead, the Monitor’s commander went aboard the receiving ship North Carolina and frigate Sabine at Brooklyn Navy Yard and asked for volunteers. More men volunteered than were needed. The chosen enlisted men would be transferred to the Monitor from early February through 6 March, the day the ship departed New York.

Worden needed firemen, coal-heavers, and ordinary seamen. Many of the men lacked naval experience, listing their prewar occupations as farmer, machinist, carpenter, stonecutter, sailmaker, or none. Volunteers with previous sea service included Seaman William Bryan, who transferred from the Sabine. Petty officers were all seasoned sailors. Quartermaster Peter Truscott (Samuel Lewis) had five years of U.S. Navy service. The use of an alias was not uncommon for sailors, as it enabled them to desert with impunity if they were dissatisfied with a posting.

Each crew member was assigned a special ship’s number on being transferred to the ironclad. Numbers 1 to 49 were members of the crew when the Monitor left New York, 1 being the first man transferred and 49 the last. John Stocking, the alias of William Wentz, enlisted as a boatswain’s mate on 25 January 1862. He was transferred from the Sabine to the Monitor as ship’s number 43.

Most of the other sailors at the Brooklyn Navy Yard thought the Monitor volunteers were foolish or suicidal. That attitude, as well as the low-lying warship’s appearance—her deck virtually awash even in calm water—and the unusual living space below her waterline, prompted several men to desert. George Frederickson noted in the Monitor’s log on 4 March, “Norman McPherson and John Atkins deserted taking the ship’s cutter and left for parts unknown so ends this day.” Coal-heaver Thomas Feeney deserted seven days after he enlisted and the very day he arrived aboard the ironclad.

Despite these problems, many volunteered for service on board the ironclad out of a sense of duty or as an opportunity to find a place in their new nation. Acting Quartermaster Hans Anderson was originally from Sweden and Seaman Anton Basting was from Germany, while Coal-heaver William (Wilhelm) Durst was a Jew from Austria. Several of the crewmen were born in the British Isles, including Seamen James Fenwick (Scotland) and Coal-heaver David Robert Ellis (Wales). Two African-Americans were among the initial crew. One was 19-year-old William H. Nichols, born a free man in Brooklyn, who enlisted as a landsman for a three-year term. While Nichols may have been urged to enlist in an effort to end slavery, others saw service as an opportunity for advancement. George Geer enlisted as a first-class fireman to earn money ($30 per month) and to learn a steady trade.

After dueling with the CSS Virginia and participating in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, the Monitor was protecting the Union Army of the Potomac’s James River flank when several escaped slaves attempted to join the crew. On 18 May an alarm sounded on board the ironclad as a small boat approached. Captain William Jeffers, then the ship’s commander, cried, “Boarders!” William Keeler “found the vast array of ‘Monitors’ armed to the teeth confronting the enemy—a poor trembling contraband begging not to be shot.” The escaped slave, Siah Hulett Carter, enlisted the next day as a first-class boy, ship’s number 53.

During the summer of 1862, the Monitor Boys endured oppressive heat and were plagued by flies and mosquitoes. Despite occasional, brief clashes with the enemy, the crew suffered enormously from boredom. In September the Monitor received a new captain, Commander John P. Bankhead, and was ordered to the Washington Navy Yard for an overhaul. The ironclad’s bottom was fouled, the ventilation system needed improvement, and her engine required repair. During the refit, the crew was given furlough, but more than a dozen sailors did not return when their leave expired. William Durst was listed as a deserter due to illness; however, he was impressed one night while drinking. His “WD” tattoo resulted in an alias of Walter Davis. Needing to replace the lost men, Bankhead called for volunteers from the unassigned seamen at the yard. Ordinary Seaman Jacob Nicklis did not wish to ship aboard the Monitor “on account of her accommodations they are very poor” but did so anyway because several of his friends from Buffalo, New York, such as Isaac Scott, volunteered.

Once her complement was filled and repairs completed, the Monitor returned to Hampton Roads. On Christmas Day 1862, Bankhead received orders to take his ship to Beaufort, North Carolina. Learning of the assignment, Lieutenant Greene warned, “I do not consider this steamer a seagoing vessel.” Jacob Nicklis wrote his father, “They say we will have a pretty rough time going around Hatteras, but I hope it will not be the case.”

Those fears were fulfilled when the Monitor foundered and sank off Cape Hatteras during the early hours of 31 December 1862 with the loss of 16 men, including Nicklis. The ship’s surgeon, Grenville Weeks, would write Nicklis’ sister that “[you] have my warm sympathies, and the assurance that your brother did his duty well, and has I believe gone to a brighter world, where storms do not come.” The side-wheel steamer Rhode Island, which had been towing the ship, rescued her survivors and returned them to Hampton Roads. Many of the ironclad’s former crew members would serve in other warships, including monitors, during the remainder of the conflict. But the time they and their former shipmates spent on board the U.S. Navy’s first ironclad would forever define them as Monitor Boys.