“Less than 1 percent of Americans have ever seen the sunset from a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier. I have.”—popular T-shirt slogan

When earlier this year I read that 2022 would mark the centennial of naval “tailhook” aviation, the news struck home with a jolt. I suddenly realized that I’ve had a personal and professional connection with this proud Navy community for nearly two-thirds of its existence . . . and for over 90 percent of my own.

Both my life and journalism career can be measured in aircraft carriers.

In its century of existence, the Navy has commissioned a total of 66 aircraft carriers (not counting the 122 small escort carriers built during World War II and dozens of all-purpose amphibious-assault ships since then). I’ve had the privilege of serving on board two and covering 20 of them on nearly 50 separate occasions.

It started with an impulse purchase. I was eight. My brother and I liked to build model airplanes, a natural hobby for two Air Force brats. But one day in 1956, I decided to try something new. I bought my first Revell warship, the USS Midway (CV-41), with her World War II–era straight flight deck. Thirteen years later, I would receive orders to report aboard her.

(Courtesy of the Author)

On 31 January 1970, I was one of several thousand sailors joining the Midway at Hunters Point Naval Shipyard near San Francisco on the day she formally rejoined the fleet. (In between model building and Hunters Point, I’d had a brief introduction to carrier life during a reserve cruise on board the USS Hornet [CVS-12.]) This would mark the start of an intense immersion into the world of aircraft carriers. When I walked down the Midway’s gangway for the last time 19 months later at Cubi Point Naval Air Station, I had experienced the full cycle of carrier operations. Over the course of 1970 and 1971, the Midway went from cold steel at a shipyard pier to combat operations in the Tonkin Gulf.

During that time, I experienced the full spectrum of a carrier sailor’s life: mundane shipboard routine, brief respites of liberty in San Francisco, Alameda, and San Diego; backbreaking around-the-clock General Quarters, damage control, and firefighting drills off southern California; the dawning excitement as our deployment departure loomed. And a magical ten-day transit of the North Pacific in springtime with a full moon low on the horizon under the brilliant Milky Way pointing our westward track. Despite operating under EMCON silence, a pair of Soviet Bear-D bombers out of Artem North jumped us a week out from Hawaii, adding an adrenaline spike to the day’s routine. We then sprinted into the Tonkin Gulf for the air wing’s first Alpha Strike against Laotian targets. A summer of around-the-clock air operations, interspersed with liberty stops in Olongapo and Yokosuka, followed.

Then suddenly for me, it was over. On 22 August 1971, I flew back to California from Clark Airbase, out-processed at Treasure Island three days later, and flew home to Virginia and civilian life. Within a few months, I began working at a local newspaper. My days on a carrier, I thought, were done.

Boy, was I wrong!

Nine years later, while working as editorial page editor at The Daily Progress, a small newspaper in central Virginia, I noticed an Associated Press article about the USS Nimitz (CVN-68). The carrier had been three weeks into her third deployment from Norfolk when Iranian militants overran the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on 4 November 1979. Like most Americans, I had followed the hostage crisis with keen interest and learned through press reports of the Nimitz’s role in the ill-fated hostage rescue mission. But what struck me about the carrier’s 1979–80 deployment was her length: In the aftermath of Vietnam, Navy leaders had tried to set a six-month limit, but the carrier and her escorts had been extended to over eight months, including 144 continuous days at sea without a liberty call. The news article revealed plans by several community groups in Norfolk to organize a mass “welcome home” celebration for the crews of the Nimitz and her two cruiser escorts.

(Courtesy of the Author)

The AP article sparked a buried memory of my own return to American soil in 1971. The chartered airliner landed at Travis Air Force Base, pulled up to the passenger terminal, and we disembarked. The terminal was quiet. There were no “welcome home” banners, balloons, or signs. We marched through, boarded a Navy bus, and headed for Treasure Island.

At the time, I was so glad to be back in “the World” that this did not bother me. Now, nine years later as I read about the planned celebration in Norfolk, it did. I felt something pulling at me to go down and cover the event.

On Monday, 26 May 1980, the Nimitz battle group came home. It was a truly emotional experience for the 7,200 sailors finally reaching port after their seemingly endless deployment. From the main deck of the cruiser USS Texas (CGN-39), I watched as President Jimmy Carter flew out in Marine One and landed on the Nimitz to greet the carrier’s crew; afterwards, he spoke by radio link to the crewmen of the Texas and the USS California (CGN-36), thanking them for their service, over the 1MC as his helicopter flew back to Norfolk,. As the three warships turned to enter Hampton Roads, a stunning sight came into view: Hundreds of sailboats and yachts dotted the roadstead, all crammed with people waving banners and flags, blowing air horns, and cheering. When we tied up across from the Nimitz at Pier 12, the entire waterfront was carpeted with thousands of family members, friends, and well-wishers.

For me, that day seemed to mark a turning point away from the frustration and angst of Vietnam toward a genuine reconciliation between the U.S. military and the civilian society it protects. And unbeknownst to me, it set in motion a series of events that would define the next four decades of my newspaper career.

(Courtesy of the Author)

The editorial I wrote calling attention to the sacrifices by the men of the Nimitz battle group appeared in The Daily Progress the next day, and then—as we journalists say—went on to wrap fish. But less than a year later, in early May 1981, it got me recruited to join Norfolk’s afternoon newspaper, The Ledger-Star, as an editorial writer.

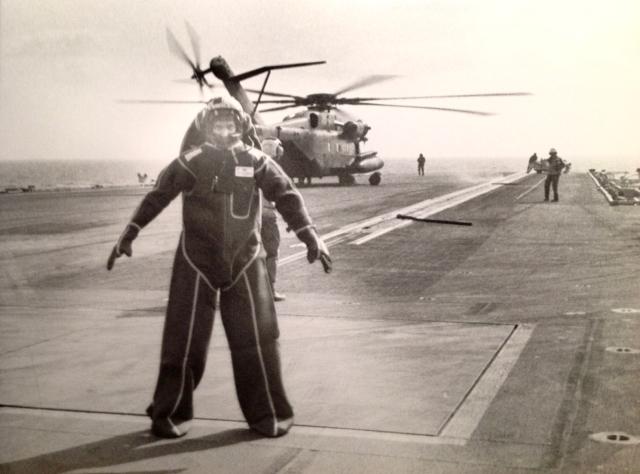

Just two weeks after I started work, the Nimitz suffered a major flight deck accident that killed 14 sailors and injured 39 more. The tragedy occurred a year to the day after the homecoming. Assigned to write about the deadly mishap, I found that I didn’t have to consult any reference books or naval histories. Memories from my service on board the Midway a decade earlier came flooding back and all but dictated my column on the dangers faced every day by the guys who work on “the roof.” I wrote:

It was a routine sortie. Another recovery in the long training cycle each carrier undergoes before deployment. . . . [But] while recovering aircraft, the carrier’s flight deck is a potential disaster area. There is very little room between perfection and mass death.

An aircraft carrier is staffed by personnel clerks, by food processors and enginemen, quartermasters and radar techs and weapon handlers. . . . In the diversity of our jobs, however, we were sharing a common role: to provide, directly or indirectly, for the ship’s ability to launch and recover its air wing.

But the men on the roof had the clearest line of sight to that responsibility.

The column was well received. My editor suggested that from now on I should focus on military and defense issues wherever possible. In Norfolk, that meant the U.S. Atlantic Fleet—particularly its aircraft carriers. I found this focus both professionally challenging and personally fascinating. Over the years, I would get to write about Army Rangers, Air Force transport missions, Marine amphibious exercises, nuclear weapons, and a plethora of other military topics. But time and time again I found myself sitting in a COD as it snagged the three-wire.

(Courtesy of the Author)

Throughout my nearly five years in Norfolk, 15 years in Seattle, and 20 years after that, I had the chance to write about carriers from an incredibly wide variety of perspectives and locations. Some examples:

I was riding in a van with some other reporters at Newport News Shipbuilding on 27 October 1984, when our shipyard escort pointed out the windshield to a bizarre landscape of giant metal shapes and forms—some several stories tall—littering a wide open field at the shipyard. “That’s the USS Abraham Lincoln,” he said with a grin. “We haven’t started gluing it together yet.” The event we were attending was the launching of the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71). Among the distinguished visitors were Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, Navy Secretary John F. Lehman, and an entire bleacher section filled with Teddy Roosevelt look-alikes.

Thirteen years later, I rode the Abraham Lincoln (CVN-72) as she crossed Puget Sound from Bremerton to her new home port at Everett, Washington. And 36 years later, in the spring of 2020, I posted online commentary lauding the crew of the Theodore Roosevelt as they valiantly grappled with the COVID-19 pandemic in Guam.

I was able to cover the USS Independence (CVA-62) three times during the final innings of her 39-year career. The first event was a world-class screw-up; the second was an impressive demonstration of the latest combat technology; the third was a moment of passing history. In 1991, I was with a news media group that flew out to the carrier as she arrived in Seattle for the annual Seafair festival, and—along with the admiral, captain, and crew—became stuck on board after mooring for four hours when it was discovered the Navy had brought the wrong-sized gangways from Bremerton to the port of Seattle. I had a more positive experience the following year when I was able to witness the latest hi-tech gear that the Navy was fielding to bolster the ship’s combat capability off the Southern California coast. Six years later, I attended her decommissioning ceremony at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard where her crew marched down the gangway for the last time.

It was a routine assignment on board the USS America (CV-66) moored at Pier 12 in the summer of 1984 that I learned once again how brutally hot a hangar deck could become. While covering a change-of-command ceremony for COMNAVAIRLANT, the event morphed into a non-TV version of “Survivor.” As the outgoing three-star reminisced without end, droning on and on, Hangar Bay One echoed with the surreal “CLANG … SPLAT!” as one by one, the Marines in their dress blue uniforms dropped their M-14s and swan-dived onto the steel nonskid.

Even the Navy budget could become an adventure: In 1982, when the admirals and Congress were wrestling over a number of major ship overhaul projects, the Hampton Roads business community went to General Quarters when it appeared that the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard (e.g. the Pennsylvania and New Jersey congressional delegations) were maneuvering to hijack a $100-million overhaul of the USS Coral Sea away from the Norfolk Naval Shipyard. After listening to one near-hysterical press conference by local business executives and labor leaders, I felt inspired to write: “It is a sign of the age we live in that the Navy, which used to name its aircraft carriers after major battles, is now naming its major battles after aircraft carriers. . . .”

This rhetorical flourish resulted in a moment of sublime professional satisfaction: I was publicly denounced by both management and labor!

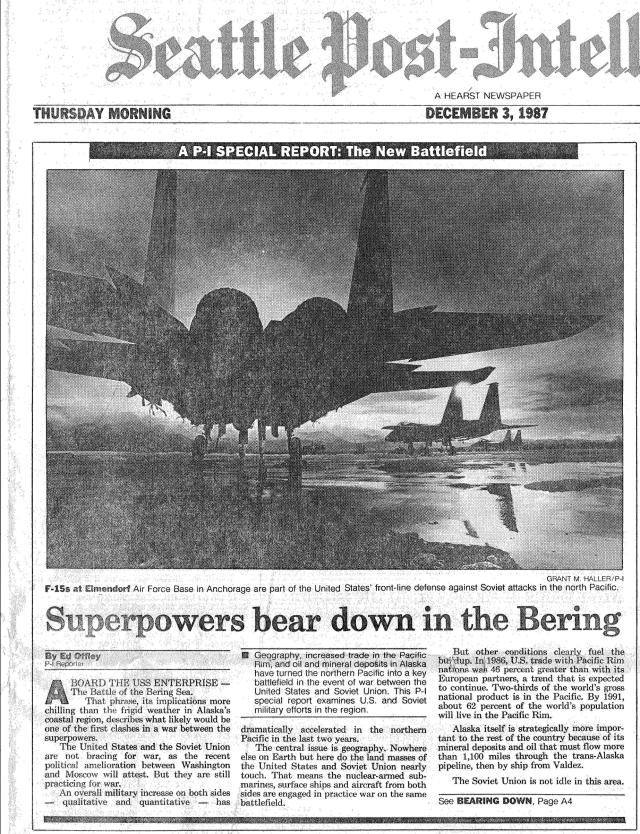

In a journalistic replication of my own brief naval service, I had the rare opportunity to cover in depth a carrier’s entire pre-deployment cycle. In early 1987, the Navy announced it was reassigning the Nimitz from Norfolk to a new home port in Bremerton. Unlike Norfolk or San Diego, where aircraft carriers had been a normal presence forever, there had not been a carrier homeported in Puget Sound since World War II. It was news.

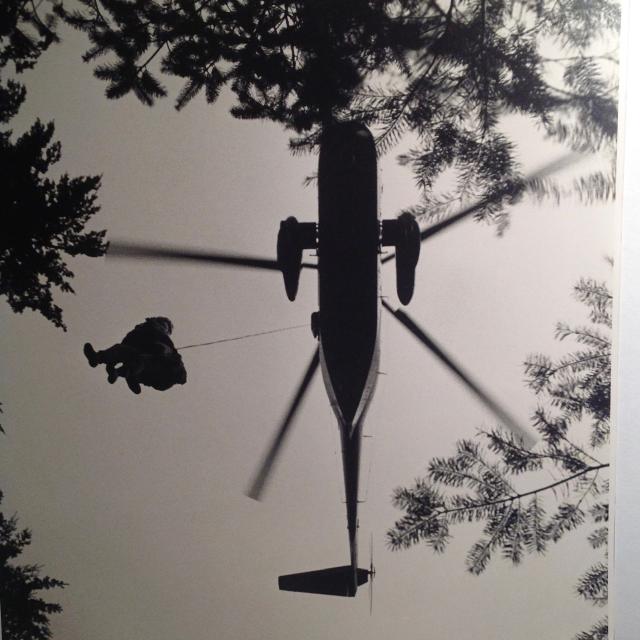

(Courtesy of the Author)

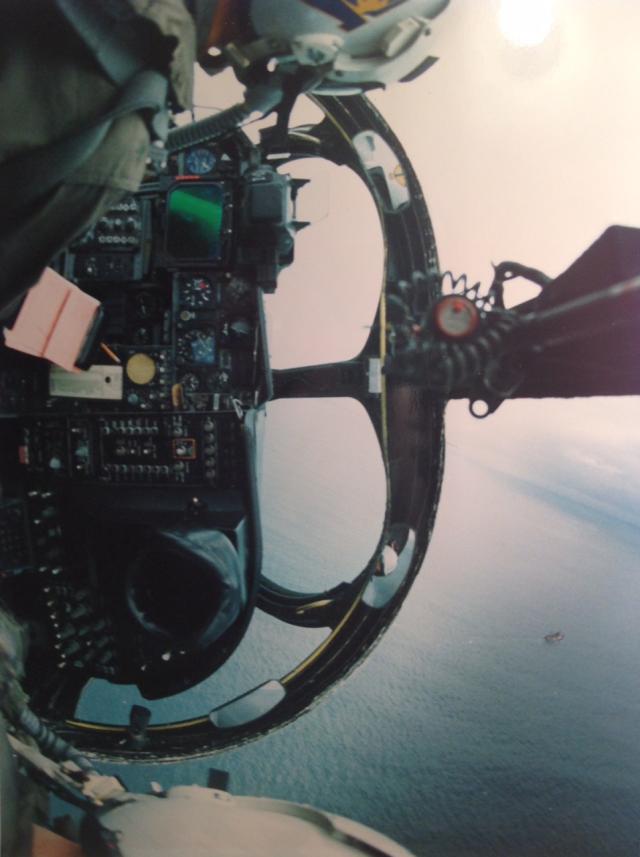

Over a 14-month period, I was able to document the arduous, complicated effort by the captain and his 3,500-man crew, along with the 2,480 members of Carrier Air Wing 9, as they emerged from a six-month overhaul and started the pre-deployment cycle. I met sailors who were on their first aircraft carrier, as well as grizzled chiefs on their third or fourth. I profiled a group of Nimitz wives as they recounted the challenge of a coast-to-coast home port shift: moving kids, pets, and family possessions across the country while their men enjoyed the easier task of rounding Cape Horn. Finally passing the water survival swim test at NAS Whidbey Island after several attempts, I learned firsthand the thrill and hazard of low-altitude flight maneuvers in an A-6E Intruder from VA-165 assigned to the Nimitz. I shadowed a young flight deck crewman fresh out of training as he worked the port catapult during a launch cycle. And I was delighted to cover captain and crew as they edged the Nimitz through Rich Passage and headed north in Puget Sound to begin the ship’s seventh deployment on 2 September 1988.

Twice embarked on a carrier, and once sitting at my newsroom desk (thanks to satellite phones) I covered a real-world encounter between a carrier and a potential adversary, In September 1987, I was on board the USS Enterprise (CVN-65) in the Bering Sea when a Soviet AGI surveillance trawler shadowing the formation suddenly changed heading and was on a collision course. The Enterprise went hard over on the helm, averting a major accident. The next year, I was on board the Midway in the Sea of Japan during Team Spirit 1988. A quiet night in pri-fly talking with the Air Boss suddenly screeched to a halt when the ship received a warning message from an EP-3 patrol plane that several Soviet bombers had just lifted off from their base near Vladivostok; the ship went to General Quarters, and several Alert 5 fighters went roaring off into the night. “You’ve got to be careful in these waters,” the Air Boss said. “One false move on your stick and you’ve defected by mistake.”

The most fascinating event involved, yet again, the Nimitz. In March 1996, a sudden flare-up in tensions between Taiwan and mainland China prompted the Pentagon to divert the carrier from an ongoing Indo-Pacific deployment, rushing it north to make a freedom-of-navigation passage through the Taiwan Strait—the first carrier to do so in 25 years. In a strange inversion of the Navy’s allergy to telling reporters anything about current, much less future, operations, I answered the phone one day to find a PAO contact asking if I would be interested in interviewing the Nimitz battle group commander by satellite phone hookup. The call went through, I had engaging interviews with the admiral, the carrier CO and the air wing commander, and my article began with a paragraph that I never thought possible: “When Chinese air-defense radars detect the aircraft of Carrier Air Wing 9 tomorrow night, it will signal that the USS Nimitz has entered the Taiwan Strait. . . .”

(Courtesy of the Author)

In addition to the ships themselves, my coverage over the years brought me into contact with many naval officers whose service would lead them to high rank. My encounters with these men greatly increased my own knowledge of issues vital to naval aviation. These included Joe Prueher, Brent Bennitt, Lyle Bull, Stan Arthur, Richard Macke, John Nathman, Ron Zlatoper, and Leighton Smith among many others. Two surface warfare officers who also served with carriers included David E. Jeremiah and Bill Center. Two naval aviators I had the pleasure to cover who followed non-traditional paths to national leadership were Navy Reserve A-6E Intruder B/N, John F. Lehman, and former A-4 pilot John McCain.

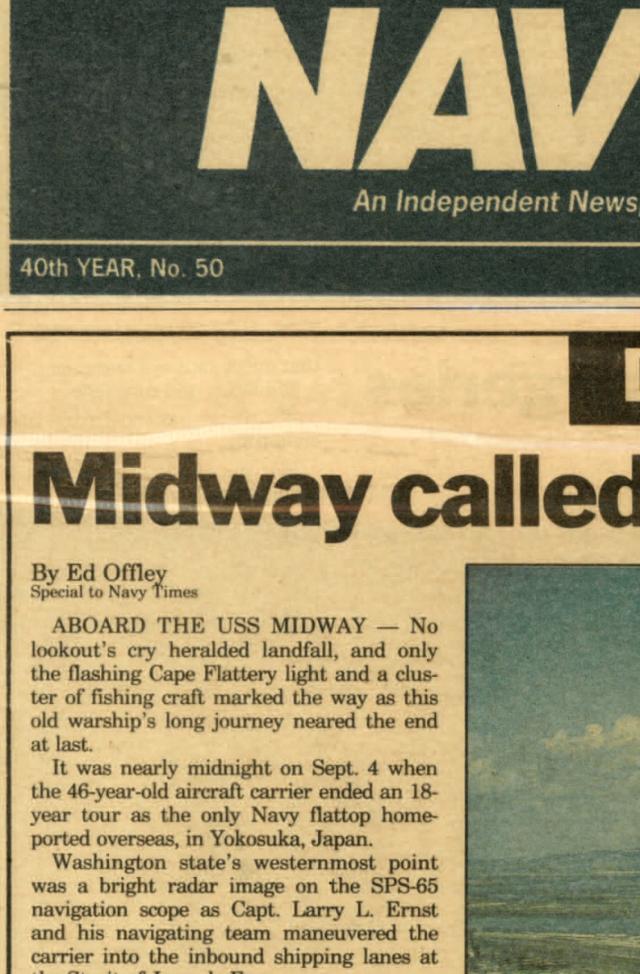

In the end, two of my most treasured stories involved homecomings. In September 1991, the Midway entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca after a trans-Pacific crossing from its home port in Yokosuka, Japan, en route to its decommissioning in April 1992. The carrier’s three-day Seattle port visit offered me the chance to make a final trip on board her. In my Navy Times “farewell” article, I noted the carrier’s lengthy history and accomplishments:

The Midway is closing out a career that spans three generations of U.S. Navy sailors, and a tenure that started with Navy design teams at work a year before Pearl Harbor and is ending after the virtual collapse of the Soviet threat. Her history is a litany of peacetime, crisis and wartime operations from the Arctic Ocean to the eastern Med, the U.S. West Coast to the shores of Africa, from the Tonkin Gulf to the Persian Gulf. . . . Her first planes were prop-driven fighters, and her last cruise brought the supersonic F/A-18 fighter-bombers of Strike Fighter Squadron 151 back to the U.S. mainland for reassignment.

(Courtesy of the Author)

After recounting the Midway’s role as flagship of the Persian Gulf carrier force in Operation Desert Storm, one pilot summed up: “This is an old ship,” he said. “It’s beat up, it leaks. It’s an old boat. But, boy do they do a lot with it.” My piece concluded: As the sun rose over Puget Sound, Midway’s men manning the rail were still unable to think of their ship in the past tense.”

For a long time, I thought my Midway homecoming article would mark the culmination of my long association with the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers. And once again, I was wrong. Last year, my long journey came full circle.

(Courtesy of the Author)

Once more, it was an Associated Press article reporting the upcoming homecoming of an aircraft carrier after a prolonged, frequently extended deployment to the Middle East due to a flare-up of tensions with Iran. Young men and women served long hours and endless days in a far and distant hostile zone, with scant opportunities ashore, while carrying out a vital yet unheralded mission. And it was the USS Nimitz. I wrote: “As its crew disembarks in Bremerton for the first time in 340 days—the longest overseas mission by an aircraft carrier since World War II – the sailors and Marines can be proud of both their victory over COVID-19 and their ship’s operations from the South China Sea to the Persian Gulf and back.”

Forty-one years after I chronicled the Nimitz’s celebrated homecoming from Iran, I got to do it all over again.

Happy Centennial, naval aviators, wherever you may be. I’ve enjoyed the long ride with you.