The Sea Services of the United States today find themselves facing the rapid expansion of the naval power of their Cold War adversaries, which are aggressively challenging the existing world order. Of particular concern is the growing naval power of China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). In 2020, the leaders of the U.S. naval services laid out their plan of action to meet this challenge in the next decade—Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power. This document makes the case for better integration among the services and with U.S. multinational partners and states, “We must strengthen our alliances and partnerships—our key strategic advantage in this long-term strategic competition—and achieve unity of effort.”1

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) has been the primary allied mutual defense organization for more than 70 years and has done well to meet the threat to the rules-based international order posed previously by the Soviet Union and now from a resurgent Russian Federation. However, no such overarching defense organization exists for the Indo-Pacific region, where Chinese actions threaten the established order. To meet the goals of Advantage at Sea, the Sea Services must reexamine and enhance allied interoperability in the Indo-Pacific region. As part of that process, they should study the history of the ill-fated American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, formed in late 1941 in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, and take lessons from its creation and demise on how best to conduct allied combined operations when faced with an intelligent and aggressive adversary.

Marry in Haste, Repent at Leisure

On 7–8 December 1941, war in the Pacific was thrust on the Allies with the simultaneous surprise attacks by Japan on U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor, Guam, and the Philippine Islands, and on British forces in Hong Kong and Malaysia. When diplomatic efforts to head off a confrontation with Japan had failed in late November 1941, the future Allies were sure that hostilities were imminent. An attack by Japan to acquire the natural resources it needed in the Dutch East Indies was easy to predict, as was its desire to dislodge the British from China.

Since 1940, U.S., British, and Commonwealth naval commanders had been conducting joint planning outside of any formal alliance against the threat posed by the German Kriegsmarine in the Atlantic. Little headway, however, had been made in planning the defense of the Pacific. In the case of war there, the British and Dutch hoped for U.S. intervention, but lacking an attack on American territory, that would be politically impossible, and efforts to formulate a common plan of defense in the Pacific were unproductive.2

The Allies had a fundamental disagreement about how to prioritize the defense of the southwest Pacific. At a preliminary planning conference held in London in January–March 1941, British planners had suggested that the U.S. Navy provide capital ships to defend Singapore, as the Royal Navy was already stretched to the breaking point with its commitments in the Atlantic and Mediterranean theaters. Their American counterparts replied that keeping the Pacific Fleet intact was the United States’ first priority, and with the Japanese occupation of French Indochina, the defense of Singapore would be extremely difficult.3 In fact, the naval base and fortifications at Singapore were unfinished, having been the victim of on-again, off-again funding since the creation of the base in the wake of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty.

The difficulty defending Singapore from sea landings on the Malay Peninsula had been demonstrated as early as 1925.4 The key to defending the base in 1941 was air power to defend both the land and sea forces that would be tasked with repelling such landings. Unfortunately, the Royal Air Force (RAF) was no better off than the Royal Navy; its best pilots and aircraft were needed for the defense of Britain and Malta. As a result, 80,000 men were sent “to guard airfields that contained no adequate air force, and . . . these airfields had been built to cover a naval base that contained no fleet.”5

The prewar U.S. Rainbow and Orange war plans had assumed that the Philippines would fall eventually to a Japanese onslaught, so the goal was to delay the inevitable as long as possible while the Pacific Fleet moved westward from Pearl Harbor. However, the U.S. Army and Navy commanders in the Philippines had warned as early as 1934 that the defense of the archipelago would be a forlorn effort at best.6 With independence for the territory slated for 1946, Congress was loath to commit much in the way of funding for the Philippines.

In 1936, Philippine President Manuel Quezon hired recently retired U.S. General Douglas MacArthur to command the newly created Philippine Army and to oversee the improvement of its training and the defense plans for the territory. In July 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt federalized the Philippine Army and recalled MacArthur to active duty to command the combined U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). Between August and December 1941, additional U.S. Army troops and aircraft arrived, but their late appearance would allow little time for training or coordination with the Philippine Army before the Japanese struck.

The naval defense of the islands would be provided by the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, based at Cavite in Manila Bay and commanded by Vice Admiral Thomas C. Hart. Hart had begun a process of overhaul and increased training as tensions in the Far East increased, but the fleet—which consisted of just one modern heavy cruiser, one light cruiser, and a collection of older destroyers and submarines—was intended primarily to show the flag and was inadequate to the task. MacArthur, however, was relying on the 29 submarines of the Asiatic Fleet to destroy Japanese troop transports before landings could take place; in turn, Hart was relying on the USAFFE to provide air cover for his submarines, which were believed to be vulnerable in the shallow waters around the Philippines, as well as protection for Cavite. Both men were to be bitterly disappointed.

Japan Attacks

In the early afternoon of 8 December, Japanese bombers and fighters flying from Formosa hit Clark Field, the primary air base in the Philippines. Radar had provided just enough warning to alert U.S. aviators there but not enough time for most of them to take off; many of the fighters that scrambled were caught taxiing on the ground. The few that managed to take off in the confusion were damaged or destroyed in combat with Zero escort fighters. Cavite Navy Yard, now virtually defenseless except for a handful of obsolete antiaircraft guns, was hit on 10 December and destroyed over several hours. The highly trained Japanese airmen could select and destroy targets at will, including most of the supply of torpedo reloads for the Asiatic Fleet’s submarines.

Without air cover, the fleet was extremely vulnerable, and Hart decided to move his forces south to Australia to preserve as much of them as he could.7 Due to a combination of bad luck, bad doctrine, and bad torpedoes, Hart’s submarines did little to hinder the landing of Japanese troops in north Luzon, which began on 12 December (see “Bleak December,” December 2021, pp. 26–33).8 The cream of the Japanese Imperial Army easily pushed aside defenders and began its inexorable advance on Manila, with MacArthur’s poorly trained forces falling back to hastily arranged lines of defense that were quickly overrun. Christmas 1941 saw U.S. forces evacuating Manila and withdrawing to the bastion of Bataan.

On the same day Japanese aircraft had hit Clark Field, they bombed Singapore and landed troops on the Malay Peninsula and in nearby Thailand, having sailed from Indochina. After a few hours of resistance, the Royal Thai government capitulated and signed a treaty of friendship with Japan. As Japanese troops began their push down the Malay Peninsula, Royal Navy Force Z—composed of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, the battle cruiser HMS Repulse, and four destroyers—sortied from Singapore to attack the landing operation. The Force Z commander, Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, was under the mistaken belief that RAF aircraft would provide cover. Instead, Imperial Japanese Navy land-based bombers and torpedo bombers struck and sank the Princes of Wales and Repulse on 10 December in a masterful display of aerial tactics, proving that capital ships without air cover were sitting ducks. Singapore was now open to attack by land, sea, and air.

The Birth of the ABDA Command

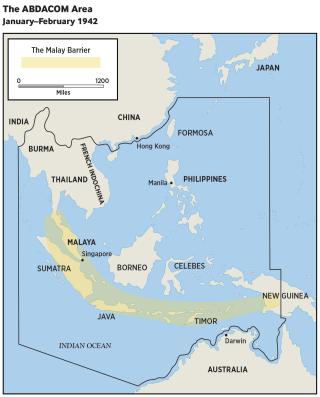

Japan’s attacks brought the United States into the war at last. On 1 January 1942, the new Allies meeting at the first Washington Conference (code named Arcadia) created the ABDA Command (ABDACOM) almost as an afterthought to the primary result of the conference—declaring a “Germany first” policy for the conduct of the war. It was recognized, however, that the stunning Japanese successes required some response, and so resources were set aside for that purpose. The primary task of the ABDACOM would be to hold the “Malay Barrier,” centered on Singapore, to keep Japanese forces out of the Indian Ocean and to keep the sea lanes to Australia open. While this was the correct strategy, it was one that effectively ignored the defense of the Philippine Islands, which by now was looking increasingly hopeless—as the prewar planners had predicted.

One of the lasting effects of the creation of the ABDA Command was giving proof of concept for the creation of a joint Allied command. Instead of three national forces—American, British/Commonwealth, and Dutch—each acting independently, with its own ground, air, and naval forces accustomed to acting with a large degree of autonomy, now all, in theory, would be in a unified command overseen by a single man, in this case British General Sir Archibald Wavell. U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall, with the willing acquiescence of U.S. Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ernest King, had suggested that the commander of ABDACOM be British, an idea to which British Prime Minister Winston Churchill gladly acceded.9 Churchill, in turn, suggested that the naval commander be an American, and Admiral Hart was appointed to the position. ABDACOM would receive direction from an Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff, located in Washington, setting the pattern for a unified Allied command structure for the rest of war.

Wavell was perhaps the natural choice, as he was then the commander of British forces in India. Previously he had faced Erwin Rommel in North Africa, but now he was given an even tougher job, with scant resources and facing an even more determined and better equipped enemy. He arrived in Singapore on 7 January 1942 to take command of ABDA COM, but with the relentless drive of the Japanese Army down the Malay Peninsula, he was forced to relocate his headquarters to Lembang, Java, on 18 January. He faced an extremely difficult situation. Wavell found that his military forces were completely committed to the defense of their respective territories and unavailable for offensive operations outside their immediate areas of operations. The Allied air forces were little better. The U.S. Far East Air Force was shattered, and its major elements withdrew to Australia. The British and Dutch RAF regional commands, equipped with obsolete aircraft, were hard pressed to defend their respective air space above Singapore and Java and suffered high rates of attrition.10

The Navy Strikes Back

Only the naval forces under Admiral Hart, slapped together into a so-called Combined Strike Force, had the ability to conduct offensive operations. Without air reconnaissance, however, Hart was in the dark as to the location of Japanese invasion forces. Luckily, an observation by a lone PBY flying boat in the Makassar Strait enabled his force to achieve its one victory, at Balikpapan on the east coast of Borneo on the night of 24 January 1942 (see “First Strike,” February 2022, pp. 26–33). It was a tactical victory resulting in the sinking of several anchored transports and a patrol boat; while good for morale, the feat did nothing to slow the Japanese takeover of the oil refineries there.11

Meanwhile, the Dutch were resentful that they had been kept out of ABDACOM’s high command. Thanks to the combined efforts of their embassy in Washington and the bitter complaints of Douglas MacArthur about the failure of the Navy to prevent the landings at Luzon, Hart was pressured into resigning his command of ABDA naval forces “for reasons of health,” to be replaced on 15 February by Dutch Vice Admiral Conrad Helfrich.12 Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman was now placed in command of the Combined Strike Force.

In perhaps the worst defeat of arms in the history of the British Empire, Singapore fell on the on the same day that Hart left his command. The “cornerstone” of the British defense plans for the Malay Barrier was gone, and the way for Japanese incursion into the Indian Ocean was open. As far as the British were concerned, the rationale for ABDACOM was gone. Aware that the fall of Java was just a matter of time, the Combined Chiefs ordered Wavell to return to India, and he handed over what was left of the ABDA Command to the Dutch on 25 February 1942.13

Admiral Doorman attempted to interrupt the Japanese invasion of Java on 27 February in what became known as the Battle of the Java Sea. Because his American, British, and Dutch subordinates lacked common code books, Doorman had to communicate with light signals and ship-to-ship telephones in plain language, relying on an American liaison officer to translate his orders. Without joint tactical training, his force’s multinational ships had to form on Doorman’s flagship in a line-ahead formation. Lacking air cover, his doomed fleet put up a brave fight but was virtually annihilated by a combination of superior Japanese tactics and Long Lance torpedoes during the fight. The Dutch flagship, the light cruiser De Ruyter, was hit by torpedoes and sank, taking Doorman with her.

On 1 March 1942, Admiral Helfrich released what was left of the U.S. and British naval forces, which retreated to bases in Australia and India. Java surrendered on 8 March 1942, and the ABDA Command was no more.

The Lessons of ABDACOM’s Failure

The ABDA Command lasted two months, perhaps the shortest lived major command in the annals of World War II. In combat operations, the Japanese used surprise attacks to gain an initiative they never lost. They destroyed the bulk of the Allied air forces at the outset and maintained air dominance throughout the theater of operations and local air supremacy wherever they attacked. At sea, the lack of air cover forced the Combined Strike Force to seek battle at night, a fight for which the IJN was far better prepared. Without a common tactical doctrine or signal code and facing language difficulties, the Strike Force was reduced to groping in the dark, in follow-the-leader fashion, and paid dearly for it.14

In terms of men and matériel, Allied losses in the southwest Pacific theater were surpassed only by Soviet losses the year previous; regarding territory conquered, it far surpassed Adolf Hitler’s conquests in Europe. In terms of strategic value, the elimination of the ABDA Command provided Japan with unmatched access to the oil, rubber, metals, and other strategic resources so desperately needed for its war in China.

What were the reasons for Japan’s success and the failure of the ABDA Command? First, a failure at the strategic level. While the grand strategy of defending the Malay Barrier and preserving the U.S.-Australia line of communications was the correct one, the putative Allies were stuck in their prewar, outdated strategic paradigms that required them to defend their colonial territories without Allied help, territories they knew were difficult to defend against seaborne invasion. Even worse, for reasons of political necessity and the demands of empire, they continued to pump men and matériel into the doomed enclaves.

Second, the Allies had failed to plan for simultaneous surprise attacks by Japan, hoping they would have time to react to bring fresh forces into the theater. Instead, they were forced to create an ad-hoc collective defensive strategy from scratch, to be managed by a “unified” command cobbled together from elements that had never worked together, spoke different languages, and operated within very different military cultures.

Third, the Allies, hoping that the opposing forces would conform to their prewar prejudices, grossly underestimated the capabilities of their adversary. Finally, ABDACOM was never truly a unified command. Although with near-superhuman efforts it had tried to make it so, their last-minute efforts failed to correct the neglect of years.

A Present-Day Patchwork of Alliances

The existing Indo-Pacific partnerships are a patchwork of bilateral treaties and overlapping, but not mutually supporting, defense arrangements and agreements. With the ANZUS Treaty of 1951, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand created a mutual defense coalition of in response to the Chinese intervention in the Korean War. SEATO, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, was created to be a Pacific analog of the NATO alliance and included the ANZUS nations, as well as Thailand, Pakistan, the Philippines, France, and the United Kingdom. Some members participated in the defense of South Vietnam, but in 1977, two years after the fall of Saigon, it formally was disbanded.

New Zealand’s declaration to be a nuclear-free zone led to the United States suspending its treaty obligations with that nation in 1986.15 The United States has mutual defense treaties with the Republic of Korea and Japan, but these are not mutually supportive. In any event, it is unlikely that South Korea would act without a direct provocation, and Japan is forbidden by its constitution to do anything other than defend its Home Islands. The so-called Five Eyes Intelligence Alliance, kept secret until recently, provides for mutual intelligence sharing only by Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It has its origins in the Atlantic Charter and the UKUSA Agreement of 1946.16

More recently, the trilateral security pact AUKUS among Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States was announced, providing a mechanism whereby the United States and United Kingdom can transfer classified technology to enable Australia to build and equip its navy with eight modern nuclear-powered, but conventional weapon-equipped, submarines.17 This was hailed as a major step forward in allied cooperation, but the agreement does not include any new mutual defense arrangements.

In a worrisome development, China signed a security agreement with the Solomon Islands in March 2022 and is seeking diplomatic ties with ten other Pacific island nations, ones that the United States expended much blood and treasure to wrest from Japan in Pacific war campaigns.18 China had been negotiating the security deals for many years, and the arrangement could place Chinese forces athwart the U.S.-Australian line of communications that the Battle of Guadalcanal was fought to preserve. Recently retired Australian Major General Mick Ryan termed this development a “massive strategic failure” by the Australian government and said it presents “the most profound strategic challenge in our region since the Second World War.”19 This demonstrates the absolute need for a unified approach to the Chinese challenge if such failures are to be avoided in the future. The fractured nature of the current web of alliances and agreements does not bode well for a rapid and unified response in the face of a determined aggressor.

A Way Forward

Fortunately, the United States and its Indo-Pacific partners have an existing framework in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) on which to build an effective interoperative command to avoid the fate of the ABDA Command. A lineal descendent of the original World War II CINCPAC (Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command), USINDOPACOM is located at its predecessor’s same base on Oahu, Hawaii.20 There, the Department of Defense’s service branches are united under the command of a four-star admiral, providing a ready template for multinational, interservice cooperation. To avoid another Solomon Islands surprise and provide a unified front against Chinese aggression, it is imperative that command and planning staff from allied and partner air, land, and sea services be brought on board USINDOPACOM at the earliest opportunity. Existing paradigms regarding the defense of the western Pacific need to be reexamined and revised in the light of Chinese naval modernization and aggression.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz was once asked which period of the Pacific war gave him the most anxiety, to which he replied, “The whole first six months.”21 Much of his angst could have been attributed to the failure of the ABDA Command. To avoid another such period of intense anxiety, the same level of planning and integrated joint operations that NATO members enjoy today must be translated into the Indo-Pacific region. Only through a unified, integrated response will the aggression of rogue nations be met and defeated.

1. Advantage at Sea, Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power. CNO ADM Michael M. Gilday, USN, GEN David H. Berger, USMC, and ADM Karl J. Schulz, USCG, are the leaders of their respective services and are the named authors of this document.

2. James Leutze, A Different Kind of Victory: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Hart (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983), 179–82.

3. Samuel Elliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 3, The Rising Sun in the Pacific, 1931–April 1942 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010 edition), 49–50.

4. Barry D. Hunt, Sailor-Scholar, Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, 1871–1946 (Waterloo, ON: Wilfried Laurier University Press, 1982), 147. VADM Herbert W. Richmond was the commander of the East Asia Station and conducted landing maneuvers to prove the point. Richmond, a keen historian, also pointed out that fortified naval bases could not hold out indefinitely; they required relief from a naval force capable of driving the attackers away.

5. Paul Kennedy, quoting Basil Liddell Hart, Victory at Sea (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022), 226.

6. Steven J. Pedler, “Whistling Past the Graveyard in the Philippines: The Upham-Parker Letter of 1934,” paper presented at the Society for Military History Conference, 2011. ADM F. B. Upham, USN, and GEN Frank Parker, USA, commanders of their respective services in the Philippines, wrote a joint letter to the War Department warning that the defense of the islands “in the event of an Orange War is impossible of accomplishment.”

7. Leutze, A Different Kind of Victory, 242.

8. CAPT James P. Ransom, USN (Ret.), “Bleak December,” Naval History 35, no. 6 (December 2021): 26–33.

9. Ian Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 188–90. Marshall suggested a British general to sell the concept of a unified command, which was paramount. King much preferred that the Asiatic Fleet be under the direction of Wavell than the imperious Douglas MacArthur.

10. The mainstay of the Allied air forces was the Brewster F2A Buffalo. While effective against older fighters, by 1941 it was hopelessly outclassed by the Mitsubishi Zero.

11. John G. Domagalski, “First Strike,” Naval History 36, no. 1 (February 2022): 26–33.

12. Leutze, A Different Kind of Victory, 277. It was said that 64-year-old Hart was too old and frail to be an effective commander. Ernest King defended Hart as best he could, but President Roosevelt, also under pressure from Winston Churchill, demanded that Hart step down. Thanks to King, however, he retained his four stars and remained in active service until the end of the war.

13. Toll, Pacific Crucible, 252.

14. “Combat Narratives: The Java Sea Campaign,” Office of Naval Intelligence, U.S. Navy, 1943, 67.

15. “The Australia, New Zealand, and United States Security Treaty (ANZUS) 1951,” U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian.

16. “Newly Released GCHQ files: UKUSA Agreement,” June 2010, National Archives, Kew, Richmond, UK.

17. “Australia Signs Nuclear Propulsion Sharing Agreement with UK, US,” Dzirhan Mahadzir, USNI News, 22 November 2021.

18. “China Foreign Minister Arrives in Solomon Islands Amid Security Deal,” Japan Times, 26 May 2022.

19. MGEN Mick Ryan, RAA (Ret.), Proceedings Podcast, Episode 265, 21 April 2022.

20. “History of the Indo-Pacific Command.”

21. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), 175.