While many naval ships are historic, the comparatively small number of great historic warships owe their status to the men who served on board them. Other historic ships are memorable because of the men otherwise connected to them and the vessels’ places in history. Such is the case of the Lightning. Even though she was not a ship, was never commissioned, fought no battles, and performed no heroics, she nevertheless is historic.

Perhaps the most unlikely of “New Navy” advocates in the late 19th century was Admiral David Dixon Porter. Steeped in “Old Navy” tradition, the Civil War hero decried the reduction of sails and spars on warships as late as 1886 and called for the rearming of 11 rusting Union monitors. But he laid the groundwork for great advances in torpedo technology, design, and use in the U.S. Navy. His foremost promotion of torpedo warfare within the service had its roots in his authorization of Lieutenant William B. Cushing’s audacious and successful plan to sink the Confederate ironclad Albemarle with a spar torpedo on 27 October 1864.

In the wake of the 1870 death of the Navy’s first full admiral, David G. Farragut, Porter was promoted to that rank as the senior officer of the Navy and confirmed by the Senate in January 1871. This was a lifetime appointment; although without fleet command, it had the responsibility “to lay before the Secretary of the Navy a report on the present condition of the Navy and offer such professional suggestions as may further promote its discipline and efficiency.”

During Adolph E. Borie’s brief 1869 tenure as Secretary of the Navy, one of Porter’s primary concerns was the state of torpedo warfare within the service. In July, he convinced Borie to organize a “Torpedo Corps” and establish a torpedo station at Goat Island off Newport, Rhode Island. The corps was assigned total responsibility for developing the torpedo as a weapon, from concept to tactics—including the design and purchase of ships and boats. The station had three distinct functions: experiment, manufacture, and instruction.

At Newport, the Navy, and in particular Porter, became introduced to yachts manufactured by a blind designer and builder, John Brown Herreshoff. His business later became the Herreshoff Manufacturing Company—located about 14 miles north up Narragansett Bay from Newport at Bristol, Rhode Island—and his innovative younger brother, Nathanael Greene Herreshoff, would join the firm. In August 1870, the business’s fourth powered boat, the 38-foot steam yacht Anemone, began making demonstration runs on the bay as an enticement to the public—and the Navy—to visit the building yard.

That year, Porter spent two months in Newport observing operations at the Goat Island station and was distressed by what he found. He saw too much theoretical work and insufficient practice. There were no high-speed launches suitable for torpedo work, and he strongly advocated the Navy’s immediate publication of findings from the torpedo testing activities at Newport to better inform naval officers. An 1872 report would buttress Porter’s position by declaring an “indispensable” need for high-speed testing vessels.

In January 1871, Congress, acting largely on Porter’s recommendations, authorized $600,000 for construction of two iron-hulled, spar torpedo–equipped steam rams: the 158-foot, 340-ton Alarm (see “Historic Ships,” August 2019, pp. 12–13), built “entirely from designs by Admiral Porter,” and the 170-foot, 450-ton Intrepid. The experimental Alarm had an 11-year commission, while the Intrepid, intended as an operational warship, was wholly unsatisfactory and spent the vast majority of her eight-year commission in port. Both ships were diversions with a dated technology—the spar torpedo; not only distractions, they also wasted limited funds at a time when other navies were experimenting with “automobile,” or self-propelled, torpedoes.

By 1875, with the addition of the two spar-torpedo boats, activity at Goat Island had ramped up, but the need for a fast test hull remained. In September, the New York Daily Herald reported that Porter, on board one of the torpedo launches, participated in two experiments. In late October, a preliminary trial was run at Newport on a “new and improved torpedo boat” (a term used to describe a self-propelled torpedo in the modern sense) built by John L. Lay. In early October, the station commander, Captain Kidder R. Breese, had made an informal proposal to the Herreshoff company for a “steam-launch, suitable for a torpedo-boat.” The company responded with a $5,000 proposal for a 55-foot-long boat to be delivered before 1 April 1876. The contract for Steam Launch No. 6 was signed on 5 November.

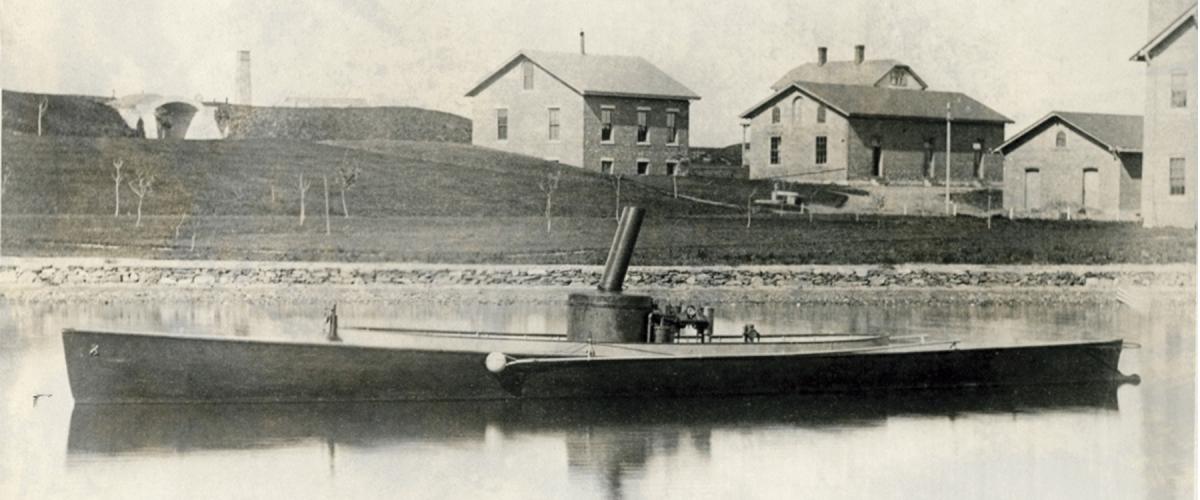

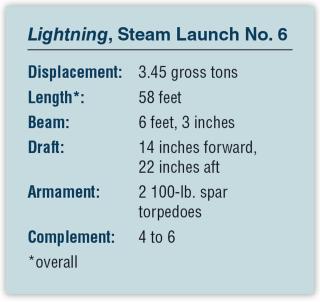

The boat, lengthened to 58 feet, was named the Lightning and launched on 19 April 1876. She ran builder’s trials nine days later. Government trials were completed on 24 May, with the Navy accepting her the next day and taking delivery on 1 June.

The Navy’s first purpose-built fast spar-torpedo boat, the craft was powered by a pair of connected engines with their crankshafts offset by 90 degrees. Rated at 60 horsepower, they could push the 3.45-ton boat through the water at 19 mph for 30 minutes and, at cruising speed, 16 to 16.5 mph. On her trials, she ran more than 20 miles at 20.3 mph. Lieutenant George A. Converse, the torpedo station’s assistant inspector of ordnance who conducted the service trials, declared the Lightning achieved “a speed which, up to the present time, has never been equaled by a boat of the same ‘waterline’ length.”

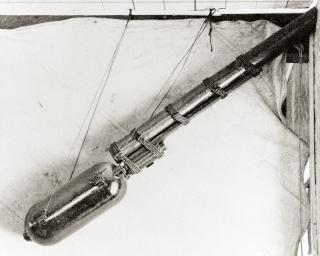

After delivery, the vessel was fitted with torpedo gear for handling two spars, one on each beam, with charges of up to 100 pounds each. It also had a small dynamo installed for electric power; this introduced electricity to the Navy. (The first U.S. warship with electric lighting was the Trenton in 1883.) Some piping was rearranged, and the exhaust pipe was slightly modified. The boat was quickly deemed ready for service as either a torpedo or picket launch.

She was immediately included in that summer’s annual torpedo officer course of instruction. When not so engaged, the Lightning was used for a number of experiments, which were deemed “quite satisfactory” with the boat “fully realizing” all expectations of speed and “general fitness” for her designed purpose. These included various spar configurations, a new mission of attacking at high speed with a towed torpedo, and signaling experiments with her electric light. It was claimed the boat could go as fast astern as forward and stop from full speed within two ship lengths.

On 28 August 1876, Admiral Porter and Vice Admiral Christopher R. P. Rodgers, the U.S. Naval Academy superintendent and president of the U.S. Naval Institute, visited the Goat Island station. After a 17-gun salute followed by a salute of 13 12-pounder torpedo detonations, they witnessed a demonstration of how quickly steam could be raised by the Lightning and the speed of the boat with two quick laps of the island. Porter was significantly impressed by not only the boat, but also the quality and level of Herreshoff’s work and pursuit of technological development.

Despite her utility and high praise from the Navy, the Lightning was the vehicle for a dead-end technology: the spar torpedo. A torpedo boat needed to be as far as possible from the scene of its weapon’s detonation—a difficult if not impossible goal to achieve when using a spar torpedo. Using a towed torpedo—as tested by the Lightning—was somewhat of an improvement, but the towing craft still had to closely approach its target.

The solution lay with the self-propelled torpedo. While this had been invented in 1866, the technology of the time greatly limited its utility. But, by a decade later, experimentation and technological advances greatly enhanced its prospects for widespread use. The Goat Island torpedo station had already conducted experiments with Lay’s “torpedo boat,” which is what today would be called a wire-guided torpedo. The genius behind the Civil War USS Monitor, John Ericsson, also submitted a prototype torpedo propelled and remotely guided by compressed air provided through a trailing hose.

The Lightning could contribute nothing to the newer technology, thus she simply faded away, including from the record books.

But Porter was not done with Herreshoff. In his 15 November 1886 “Report of the Admiral of the Navy,” he was most effusive: “We have in this country a man of great genius engaged in the construction of marine engines and boilers, but we are blind to his merits. I allude to Mr. [John Brown] Herreshoff.” In the report, Porter envisioned a 150-foot steel torpedo boat with a quadruple expansion engine, Herreshoff boilers, Ericsson torpedoes, and a top speed of 30 mph.

The admiral did not dismiss heavy ships and guns, because torpedoes are “but adjuncts in war, although powerful ones.” Porter did, however, “recommend” that 20 such envisioned ships “be constructed as soon as possible.” He added, “These vessels, of course, should be designed by the Messrs. Herreshoff.”