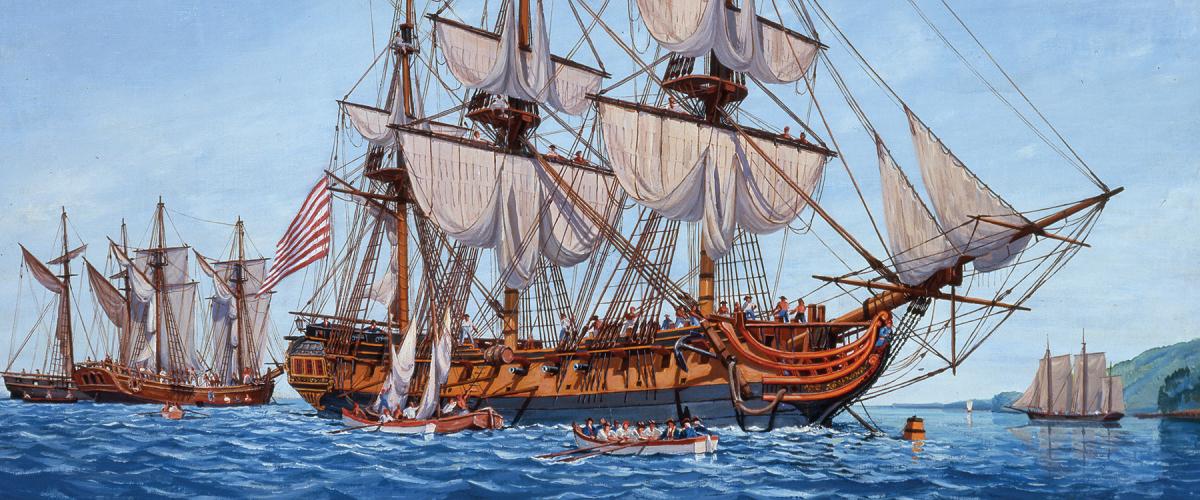

The Continental Navy’s initial warships were extant hulls that were converted to military needs. On 13 December 1775, two months after the service had been officially established, the Continental Congress passed an act to provide proper warships to the nascent navy—13 frigates of 32, 28, and 24 guns. Only eight, however, had made it to sea by the end of the war in 1783. On 20 November 1776, while those ships were under construction or fitting out, Congress passed a new act authorizing eight additional frigates—three 74s and five 36s—as well as an 18-gun brig and packet. Just two of these were completed, both of 36 guns. The Confederacy was one of those.

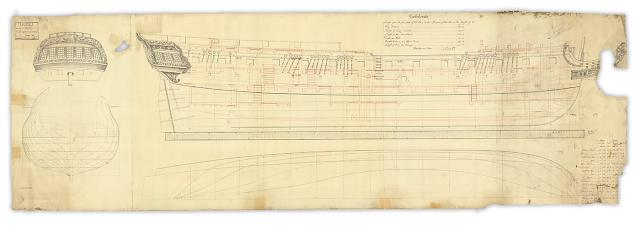

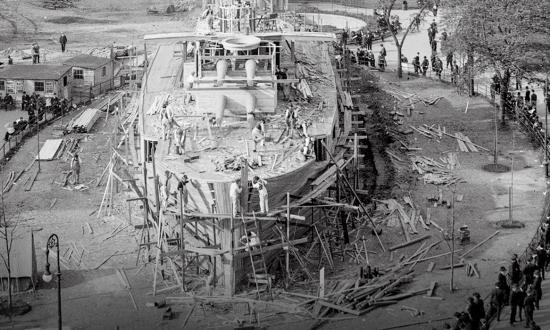

The Continental Congress assigned the shipbuilding to the various states; Connecticut was allotted one of the 36s on 23 January 1777. Its governor, on 12 February, appointed Joshua Huntington of Norwich to “superintend and execute the building of said Frigate at some proper Place in the [Connecticut] River between Chelsea and New London.” Within the week, Huntington had dispatched teams to the forests upriver to gather timber for the construction. One of his contractors wrote on 8 April: “I have a number of men in the woods getting some Perticular sticks of timber for the Ship[.] . . . Desier you to send me by the barer two Gallends of Rum which I think will be of Great Benefit to-forward the Business.”

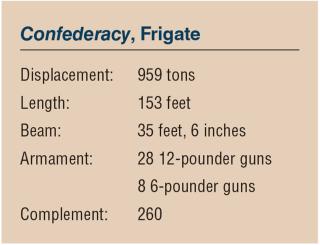

The new frigate was somewhat unusual: “ornate” and “profusely carved” and of “uncommon length.” She was “almost a galley-frigate” in that she was of a “fairly sharp model” designed for speed and fitted with sweeps on her berth deck.

By May, the keel had been laid and construction was progressing but ever so slowly, dragging on into the summer of 1778. The difficulties of ship construction while the states were literally under siege were manifest in a plea to Ambassador to France Benjamin Franklin for “Materials for a Frigate of 36 guns.” The list was extensive and included canvas for sails, rope, carpenter’s stores, anchors, and cannon. Records do not show that any of the material was obtained.

While the Navy Board expected that one foundry in Salisbury, Connecticut, would provide the guns, it produced only “several” of the weapons. The rest were borrowed from the Army or taken from British prizes. On 7 August 1778, the Navy Department wrote to Huntington that a man had been sent “to Narragansett after the anchors of the Cyrene, and for pig iron, &c.” Three weeks later, the author wrote again that he sent “a quantity of Iron which comes out of the wrecks of the men of war at N[ew] Port.”

On 25 September, the Continental Congress named the ship the Confederacy, and Seth Harding was assigned as her captain. She was launched on 7 November 1778 and towed downriver to New London for fitting out. This, too, proceeded very slowly, and the ship finally sailed on her first cruise on 1 May 1779 for convoy duty. On 6 June, in company with the converted Continental frigate Deane, she captured three prizes. The two warships safely escorted their charges into Philadelphia, where the Confederacy was laid up until October.

On 26 October, the frigate finally sailed on a proper mission: She was to transport the first French Minister to the United States, Conrad-Alexandre Gérard, and John Jay, recently appointed U.S. Minister to Spain, to France. A dozen days out of port, she was completely dismasted and her rudder was heavily damaged in a gale, forcing her under jury rig to make Martinique on 18 December. Nearly four months later, on 27 April 1780, she finally departed to return to Philadelphia, where she was refitted with new spars and rigging. During this period, the unfortunate ship was damaged in a collision while at anchor.

Her next cruise was not befitting a frigate of her standing. She was to serve as a transport for Continental Army stores from Cape François, Haiti. After sailing on 21 December for the Caribbean, her mainmast was badly damaged five days out. Once again sailing with temporary repairs, she made port in Haiti on 8 January 1781. After loading cargo and a few passengers, she departed for Philadelphia on 15 March. She never arrived.

On 14 April, off the Delaware Capes, the Confederacy was intercepted by the 44-gun fifth-rate ship HMS Roebuck and 32-gun frigate HMS Orpheus. Though Captain Harding was in command of one of the Continental Navy’s two most powerful warships, he surrendered her without firing a shot.

The Confederacy was taken to British-held New York as a significant prize. “The Rebels have suffered a great loss in this ship, as she had a very considerable quantity of Cloathing for the Rebel Army, and West India produce,” wrote Vice Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot, Commander-in-Chief of the North American Station, to the Secretary of the Admiralty. “Her length is equal to that of our old Seventy Gun Ships, and will mount Twenty Eight Eighteen Pounders on her Main Deck, is well constructed and proportioned, and only two years old.”

On 14 May, she was taken into service as HMS Confederate and rated a 40-gun ship. A month later she sailed for England, arriving at Falmouth on 19 July. While the British had great hopes for her future service, a thorough survey later that month revealed a bitter truth. Her construction of green wood came at a great price; virtually all her woodwork was “Intirely unfit for their proper service.” “The ship strains very much” and the “bottom foul and very much eat by worms.” The ship was declared “unfit for service” and broken up at Woolrich in March 1782.