As the U.S. Navy faces the challenges presented by great power competition with China and Russia, three little known exercises in 1947 suggest ways the Navy can better train to secure maritime superiority.1 Holding short-notice exercises such as those held in 1947 off Japan to take advantage of emerging training opportunities can improve interoperability with allies while revealing strengths and weaknesses of the forces involved. In contrast to the interwar Fleet Problems, the Navy’s Cold War training exercises are less well known, due in part to classification of exercise records. Examining these three exercises suggests several areas where the Navy could improve its exercise processes to take greater advantage of training opportunities.

Then and Now

Similar to today, the late 1940s were a period of rising great power competition, marked by significant technological advances. The United States and Soviet Union were increasingly at odds over the post–World War II settlement in Europe as the two nations vied for influence. The recent introduction of nuclear weapons led many observers to proclaim a sea change in warfare, similar to the concerns raised about hypersonic weapons and cyber warfare today. U.S. officials feared growing Soviet military capabilities, buttressed by advanced technology obtained from other nations—similar to China’s efforts to build on foreign technological developments.

In 1945, Soviet forces had secured access to several advanced German Type XXI submarines, their technical plans, and the engineers who had developed the boats. Type XXIs could travel underwater at higher speeds than earlier submarines, negating the strengths of most of the United States’ existing antisubmarine warfare forces.2 In 1946, the Soviets purchased powerful Rolls-Royce jet engines that were later used to power MiG-15 fighters in the Korean War.3 These growing Soviet capabilities threatened to undermine the U.S. Navy’s dominant position at sea, just as growing Chinese and Russian capabilities today challenge U.S. naval power.

Meanwhile, the postwar Navy faced significant financial and personnel problems. The end of World War II led to a massive reduction in the service’s budget. Defense spending fell from more than $80 billion in 1945 to $12 billion in 1947.4 Shipbuilding funds dried up, leaving the Navy with a large number of aging ships and limited prospects for replacement. Rising costs for individual platforms and aging ships and aircraft are an ongoing concern for the present-day Navy.

At the same time, the postwar Navy was steadily losing personnel as wartime demobilization continued. Between June and December 1947, the Navy’s officer strength fell by almost 11 percent and enlisted strength fell by more than 17 percent. In particular, the service struggled to retain trained technical personnel, such as radar technicians and communications specialists, whose skills were in demand in the private sector.5 The pull of the private sector continues to weigh heavily in personnel retention efforts today.

The August Exercises

As part of the postwar occupation of Japan, the U.S., British, and Australian navies maintained small naval forces in Japanese waters. With the establishment of Far East Command in January 1947, these forces reported to Commander, Naval Forces, Far East—U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Robert Griffin. His missions included removing minefields laid during the war and overseeing the naval demobilization of Japan. He commanded two small support groups, one British/Australian and one American, each with cruisers and destroyers that inspected Japanese shipping and provided escort services.6 While the operational duties of the occupation took up most of the command’s time, Griffin was still responsible for maintaining readiness for combat operations.

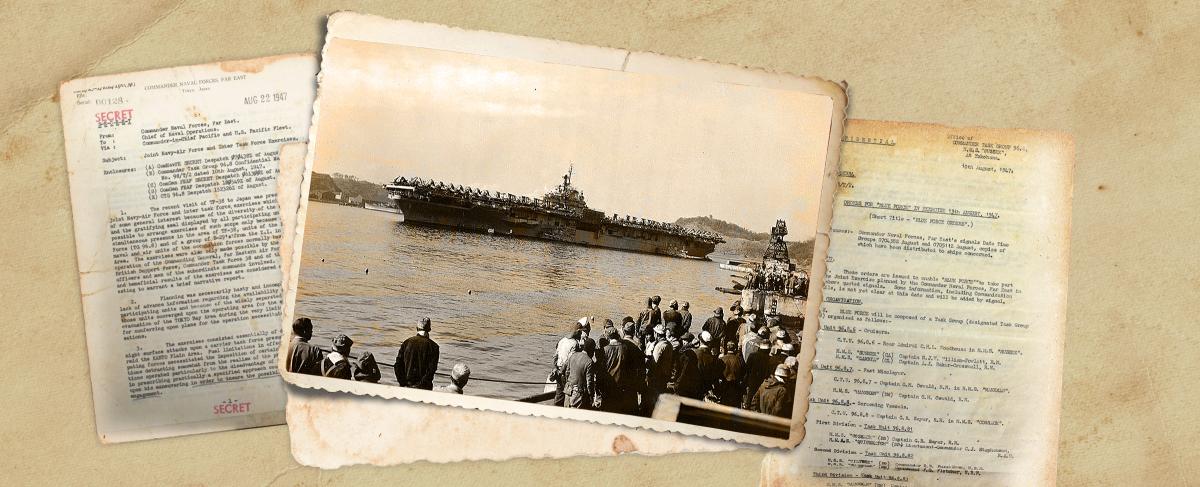

In August 1947, a visit by the aircraft carrier USS Antietam (CV-36) and the arrival of a flight of B-29 heavy bombers in Japan gave Griffin an opportunity to organize a series of exercises between the U.S. Far East Air Force, the Antietam task force, and Griffin’s Royal Navy support group, commanded by Rear Admiral Charles Woodhouse. Woodhouse’s force consisted of two British cruisers, a British destroyer, an Australian destroyer, and two U.S. destroyers. For the exercise, Woodhouse used U.S. communications and signal books, which provided an opportunity for the British and Australians to practice using U.S. Navy books.7

In the first exercise, B-29s attempted to track and launch a night attack on the Antietam, which was approaching Yokosuka from the south on the night of 12–13 August. However, Rear Admiral Samuel Ginder, the Antietam task force commander, decoyed the B-29s using radar reflectors on three of his escorting destroyers, and they failed to find the Antietam. The next morning, Ginder’s aircraft found and attacked what they thought was Woodhouse’s multinational support group. However, the Antietam’s aircraft mistook a British minelayer for Woodhouse’s cruisers while the support group hid in heavy fog. The night of 13 August, Woodhouse split his destroyers with the intention of flanking the Antietam to deliver a torpedo attack on the carrier from both sides. Two of Woodhouse’s destroyers achieved favorable firing positions on the Antietam, whose escort had been reduced to a single destroyer. Ginder had sent the other three escorting destroyers off in an attempt to engage Woodhouse at a distance from the carrier. The inadvertent passage of a Japanese merchant ship through the area ended the exercise.8

The exercises highlighted a need for better ship recognition by the Antietam’s air group, which mistook a 2,600-ton minelayer for a 9,700-ton heavy cruiser. The misdirected air strike also deprived the Far East Air Force combat patrol stationed above Woodhouse’s ships of an interception opportunity. However, Ginder’s radar decoy maneuver was a creative method of remaining hidden from the land-based B-29s. Woodhouse’s willingness to split his force at night likely reflected his experience during World War II as captain of the light cruiser HMS Ajax. During a December 1939 engagement with the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee, the Ajax and two other cruisers separated from one another to complicate the German ship’s fire control.9 Woodhouse’s tactics also reflected a willingness to engage at close range at night, which the Royal Navy had practiced extensively in the years before World War II.10 British willingness to fight at short ranges at night would crop up again in later 1947 exercises. The exercises helped Far East Air Force, U.S. Navy, Royal Navy, and Royal Australian Navy units better understand each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

Maneuvering in October

The value of the August exercises led Rear Admiral Albert Bledsoe, the commander of the U.S. support group based in Japan under Griffin, to arrange another set of exercises.11 On 3 and 4 October 1947 the cruiser HMAS Australia along with three British destroyers exercised with Far East Air Force aircraft, the heavy cruiser USS Toledo (CA-133), and several U.S. destroyers. The exercises took place within one month of being proposed, a short turnaround time that demonstrated Bledsoe’s initiative.

On 3 October, the U.S., British, and Australian ships practiced daylight maneuvering using U.S. tactical and communication books. Just before dawn on the 4th, the two forces intended to practice a night engagement, but because of a delay in making contact, the ships engaged in broad daylight. This was a potential downside of the U.S. custom of holding night practice in the hours immediately before dawn. The two forces then joined up, and the British and U.S. destroyers practiced refueling from the U.S. and Australian cruisers. The exercises concluded with a daylight strike on the formation by Far East Air Force aircraft, which took advantage of low cloud cover to attack at low altitude.12

Captain Herbert Buchanan of the Australia, a decorated World War II veteran, noted that in both the dawn surface engagement and the air attack on 4 October, “the standard of radar reporting and procedure of the American ships was below normal British standards.”13 This was likely because of the U.S. Navy’s lack of trained and experienced radar and combat information center (CIC) personnel. In April 1947 drills, the U.S. Atlantic Fleet had experienced similar delays in plotting and reporting contacts because of shortages of trained CIC personnel.14

Still, Buchanan concluded that the exercises were of “great value” and “proved that ships of the two navies can operate together at short notice.” Such small exercises, planned on short notice and allowing little time for advance preparation, provided useful training opportunities to practice basic maneuvering skills while improving interoperability. Such exercises provided realistic assessments of readiness and capabilities.

A Third Exercise

A month and a half later, Bledsoe arranged yet another exercise when a British force under Rear Admiral Robert Oliver visited Tokyo. Oliver’s squadron included the cruiser HMS Sussex and three Australian destroyers. The ships drilled for two days with a force led by Bledsoe, whose support group included the cruiser USS Duluth (CL-87) and two U.S. destroyers. On the first day, 25 November, the combined force practiced maneuvering using U.S. signal books and taking one another in tow. That night, the Australian and U.S. destroyers separated for a night attack on the two cruisers, commanded by Bledsoe. The cruisers’ mission was to escape to the south, while the destroyers sought to prevent their escape.15

During the night engagement the destroyers approached the cruisers from the south and southeast in two groups. When they were 12 miles from the cruisers, Bledsoe opened simulated fire and then turned away to the northwest, preventing the destroyers from closing to make an effective torpedo attack. The next day, the cruisers and destroyers joined up to repel air attacks from U.S. Navy aircraft and then practiced fueling. As was done in the October exercises, the British and Australian ships practiced refueling from the Americans and vice versa. A post-exercise review session allowed officers from all of the ships involved to share their views and exchange ideas while the events of the last two days were still fresh.16 The Navy’s Fleet Problems in the 1920s and 1930s had used such sessions to share perspectives and observations in the immediate aftermath of an exercise.17

Rear Admiral Oliver praised the exercises as “most beneficial” because they gave British and Australian personnel an opportunity to practice using U.S. methods. In the event of war with the Soviet Union, such practice would prove valuable. Oliver also noted Bledsoe’s decision to evade the destroyer night attack by turning away to the northwest—a violation of the exercise rules, which likely directed Bledsoe to continue sailing southeast to give the destroyers coming up from the south an opportunity to practice making a torpedo attack. Oliver concluded that “there may be a reluctance to come to close quarters at night” within the U.S. Navy.18

Bledsoe’s decision to keep his cruisers at range from the attacking destroyers was in keeping with U.S. doctrine, which emphasized the use of cruiser gun batteries and radar-guided fire control, rather than close-in combat.19 During World War II, U.S. cruisers had suffered heavily at the hands of the Imperial Japanese Navy in close-range night actions during the 1942–43 Solomons campaign, in particular from Japanese Long Lance torpedoes. In contrast, the Royal Navy had enjoyed several victories in the Mediterranean in night actions against the Italian Navy, such as at the 1941 Battle of Cape Matapan. Each side’s tactics reflected, among other influences, its recent wartime history. The exercise increased each side’s familiarity with the tactical preferences of the other, which would be valuable knowledge in an engagement.

Both admirals commented on the impact of inexperienced technical personnel on ships’ performance. Oliver noted that the inexperience of the Duluth’s CIC personnel limited the utility of the ship’s radar systems for tracking surface targets and obtaining a firing solution. Bledsoe noticed that the three Australian destroyers had difficulty keeping up with radio communications, a problem caused by the inexperience of the ship’s radio personnel.20 Both the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy were experiencing the effects of rapid demobilization and loss of trained personnel. The exercise again highlighted weaknesses in each service, a reflection of the realism of exercises arranged with little warning.

Significance for the Present and Future

The 1947 exercises suggest several lessons for how the present-day U.S. Navy trains and prepares.21 First, the Navy should standardize exercise data collection between the surface, submarine, and aviation communities. Currently, the warfighting development centers of these three communities collect exercise data in different ways. This lack of standardization hinders the ability of fleet commanders to rapidly organize and conduct exercises, as Griffin and Bledsoe did in 1947 with air and surface components. The Chief of Naval Operations should consider tasking the Commander, Naval Warfare Development Command, with pursuing this standardization to improve the Navy’s exercise capabilities. This initiative would build on the Naval Mine and Anti-Submarine Warfare Command’s work to standardize data collection in antisubmarine warfare exercises.

The Navy would benefit from greater clarity in distinguishing between training exercises and tactical development exercises. The former are intended to provide units and personnel experience in operations while building cohesion among command teams through the use of considerable freedom of maneuver or free play. The latter are focused on assessing the utility of new tactics or equipment through more scripted evolutions that ideally lead to improvements in doctrine. All three 1947 exercises were training exercises designed to give the support group staff and ship commanders opportunities to practice basic maneuvers and decision-making at sea. These objectives were established in advance at pre-exercise conferences. The Navy would benefit from being clear about the type of exercises being conducted and their objectives.

Establishing specific objectives for exercises also can help improve exercise reconstruction and speed post-exercise assessments. For example, in the October 1947 exercises, the Australians and British specifically asked to practice fueling one another’s ships, which allowed Captain Buchanan to focus on this aspect of the exercise in his report. Assigning observers to ships and aircraft in an exercise with specific areas to examine can speed post-exercise assessments, which allows participating units to benefit from exercise lessons more rapidly. Warfare development centers can continue to conduct more comprehensive analyses after these initial post-exercise assessments are concluded.

Commanders today could benefit from the initiative displayed by Admirals Griffin and Bledsoe. Both repeatedly took advantage of training opportunities as they appeared when allied ships or air force units visited Japan. Fleet commanders should pursue training targets of opportunity by tasking subordinate units with suggested training objectives and then requiring these units to submit lessons learned that can be shared across the Navy. Such lessons will allow the Navy as a whole to benefit. Given the Navy’s high tempo of operations, which necessarily limits training time, such displays of initiative are more important than ever.

Bledsoe and Griffin also ensured that their exercises included surface and aviation units. Bringing these platforms together increased realism and gave different communities experience training together. The present-day Navy devotes too much time to certification events, which come at the expense of exercises that bring together air, surface, and subsurface platforms. The heavy operational demands placed on the fleet also cut into the time available for such multi-community exercises. The Navy should seek to streamline certification standards to give units more time to participate in combined, multi-community exercises.

Finally, Bledsoe and Griffin took pains to fully incorporate allies into their training evolutions. Training with partners provided benefits in 1947 that are still relevant today. Practicing underway replenishment with allied ships and tankers helps identify interoperability problems in the area of logistics. Furthermore, replenishing at sea with partners helps maintain this perishable skill under real-world conditions. Finally, training with partners helps expose U.S. Navy personnel to the capabilities of partner navies, improving their ability to employ and integrate such capabilities. For example, exercises such as Dynamic Mongoose—an annual NATO antisubmarine/antisurface warfare exercise—allow the Navy to practice with the variable depth sonars and diesel submarines of our European partners, capabilities that are not present in the U.S. Navy. Multinational exercises under real-world conditions provide these benefits better than certification events or simulator training.

In a broader sense, exercising with allies and using such exercises to identify strengths and areas of improvement demonstrates self-awareness, an important component for a service that seeks to be a learning organization. The post-exercise critique discussions of the 1947 exercises off Japan helped U.S. officers see their service through the eyes of their foreign counterparts. The 18th-century Scottish poet Robert Burns captured the value of being assessed by others in the poem “To a Louse”:

O would some Power the gift give us,

to see ourselves as others see us!

It would from many a blunder free us,

and foolish notion.22

The Navy would benefit from embracing Burns’ words when planning exercises.

1. The views presented in this article are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of the U.S. government or the Department of Defense.

2. Jeffrey Barlow, From Hot War to Cold: The U.S. Navy and National Security Affairs, 1945–1955 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 163; Michael Palmer, Origins of the Maritime Strategy: The Development of American Naval Strategy, 1945–1955 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 39.

3. Jeffrey Engel, Cold War at 30,000 Feet: The Anglo-American Fight for Aviation Supremacy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 73–81, 118.

4. “Historical Tables,” Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2019, 2018, Table 6-1, 122.

5. First Report of the Secretary of Defense (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1948), 65–66, 141.

6. Center of Military History, Reports of General MacArthur, vol. 1 supplement, MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1994), 277–80, 288–90.

7. RADM Charles H. L. Woodhouse, RN, “No 98/5/2, Orders for Blue Force in Exercise 13th August, 1947,” 10 August 1947, Folder A16-3(1)-(16); Box 2877; Entry UD 16, Security Classified Correspondence, 1940–1947, RG 80, National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD (hereafter NARA).

8. VADM Robert M. Griffin, USN, Commander Naval Forces Far East to FADM Chester Nimitz, USN, Chief of Naval Operations, “Joint Navy-Air Force and Inter Task Force Exercises,” 22 August 1947, Folder A16-3(1)-(16); Box 2877; Entry UD 16, Security Classified Correspondence, 1940–1947; RG 80, NARA.

9. Jon Sumida, “‘The Best Laid Plans’: The Development of British Battle-Fleet Tactics, 1919–1942,” International History Review 14, no. 4 (November 1992): 696.

10. Stephen Roskill, The War at Sea, 1939–1945, vol. 2, The Period of Balance, History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military Series (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1956), 233; Joseph Moretz, The Royal Navy and the Capital Ship in the Interwar Period: An Operational Perspective (London: Routledge, 2002), 225.

11. CAPT Herbert J. Buchanan, RAN, Commanding Officer HMAS Australia to Flag Officer Commanding, Fifth Cruiser Squadron, “T/1109, Combined Joint Exercises 3rd and 4th October, 1947,” 10 October 1947, 1, 44/6, AWM78, Australian War Memorial.

12. Buchanan to Flag Officer, “Combined Joint Exercises.”

13. Buchanan to Flag Officer, 3; James Goldrick, “Buchanan, Herbert James (1902–1965),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1993.

14. VADM Arthur W. Radford, USN, Commander Second Task Fleet to Commander in Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet, “Serial 002, Report of Second Task Fleet Exercises 3 February 18 March 1947; Forwarding Of,” 10 April 1947, 1–2, B-11, Folder A4-3 (2-12/47), 1947 Secret; Box 160; Entry P 111, Secret and Top Secret General Administrative Files, 1941–1949, Commander, U.S. Atlantic Fleet; RG 313, NARA.

15. RADM Albert M. Bledsoe, USN, Commander Support Group, Naval Forces, Far East to FADM Chester Nimitz, USN, Chief of Naval Operations, “Serial 0116, Joint Exercises with Units of the British and Australian Navies—Report Of,” 3 December 1947, 622/202/4240, MP981/1, National Archives of Australia (hereafter NAA).

16. RADM Robert D. Oliver, RN, Flag Officer Commanding Fifth Cruiser Squadron to ADM Denis W. Boyd, RN, Commander in Chief, British Pacific Fleet, “CS5/T2/2009, Joint Exercises with Americans—25th and 26th November, 1947,” 14 December 1947, 5, 622/202/4240, MP981/1, NAA.

17. Albert Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010), 40–42.

18. Oliver to Boyd, “Joint Exercises with Americans,” 2.

19. Hal Friedman, Digesting History: The U.S. Naval War College, the Lessons of World War Two, and Future Naval Warfare, 1945–1947 (Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010), 152.

20. “Joint Exercises with U.S.N. Task Group 96.5,” April 1948, 622/202/4240, MP981/1, NAA.

21. The following material reflects conversations with CDR Joel Holwitt, USN; CAPT Paul Varnadore, USN; and CAPT Casey Baker, USN.

22. Robert Burns, “To a Louse.”