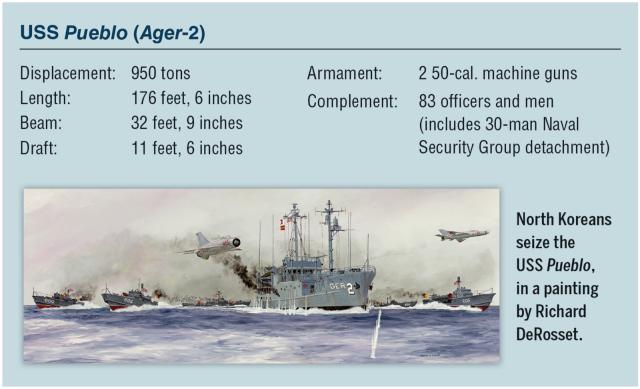

The second oldest active commissioned U.S. Navy warship began life as an Army vessel crewed by U.S. Coast Guardsmen. Despite her status as “Active, in commission,” her actual Navy service life as the USS Pueblo (AGER-2) was just 256 days. She has been a captive of North Korea for 55 years.

The ship was laid down in 1944 as the U.S. Army small freighter (Design 381) FP-344 at Kewaunee (Wisconsin) Shipbuilding and Engineering Company. Before her delivery to the Army on 5 July 1944, she was renamed and designated freight and supply vessel FS-344. She was commissioned the same month under command of Coast Guard Reserve Lieutenant J. R. Choate.

Information on her Army service is scant, with sources indicating she was used for training civilian Army crews and assigned to the area around the Philippines. One report claimed she sank a “friendly” Ecuadorian banana boat and encountered an “enemy” submarine in the Gulf of Mexico during her transit to the Pacific. The ship received both American and Asiatic-Pacific campaign ribbons for her World War II service and was placed out of service in 1954 after operating off Korea during that war.

FS-344 was transferred to the Navy on 12 April 1966 and renamed and designated the auxiliary light cargo ship Pueblo (AKL-44) that June. She began a conversion into a Banner-class environmental research ship at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton, Washington, where she was commissioned as AGER-2 on 13 May 1967 under command of Lieutenant Commander Lloyd M. Bucher. Her role also would be to gather intelligence.

During her conversion, Bucher was able to make improvements over the Banner (AGER-1); however, “his efforts to obtain a sophisticated internal system for the destruction of classified material was unsuccessful.”

After a brief shakedown cruise along the West Coast to San Diego, California, for training and to acclimate her crew to the ocean—fully half had never been to sea—the ship prepared for deployment to the Seventh Fleet in Japan. The crew completed underway training under a syllabus designed for light cargo ships, not intelligence vessels. In November, the Pueblo sailed for Japan by way of Pearl Harbor.

The ship’s maiden mission and tasking—a signals intelligence cruise along the east coast of North Korea—was primarily a testing period for the ship and crew. The mission was assigned a “minimal risk” assessment and “approved at every level in the chain of command, and all echelons, including CINCPACFLT [Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet].” Consequently, only “on call” support forces were available. Orders forbade the ship to approach closer than 13 miles from the North Korean coast.

The Pueblo left Sasebo on 11 January 1968 and proceeded to the first operating area off the northern coast of North Korea from where she worked her way south until 22 January, when she lay off Wonsan. Up to that time, she had been unobserved and received “unproductive” electronic activity. First contact was made on the 22nd when two fishing trawlers circled her while more than 18 miles from the nearest land. The two linguists with proficiency in Korean assigned to the ship were “not qualified.” The “deficiency may have contributed materially to the critical situation.” Had they been more conversant with the language, Bucher “might have had earlier warning” of North Korean intentions.

Shortly before noon on the 23rd, a North Korean SO-1 class submarine chaser approached the Pueblo, followed a half hour later by three P-4 torpedo boats and two MiG fighters. The ship was in international waters, 15.8 miles from the nearest land. As the North Koreans formed a boarding party, the Pueblo began a cat-and-mouse game as she tried to put as much distance between herself and the coast as possible. At 1327, the Koreans fired a warning shot that hit the radar mast and wounded three men. Bucher decided the Koreans would make a “full-scale incident” and ordered all classified material destroyed. Sporadic Korean firing then followed.

The Koreans boarded the Pueblo at about 1432. By 2030, she was docked at Wonsan with one killed and ten wounded. The crew were subjected to torture throughout their subsequent 11-month incarceration (see “Hell and Back,” February 2018, pp. 42–47). “An atmosphere of terror and intimidation was prevalent throughout detention.” The crew was repatriated at Panmunjom on 23 December 1968.

The ship—remaining in U.S. Navy commission—is in North Korean custody, docked at the capital city of Pyongyang.

One officer subsequently wrote: “[T]he silence from our shore-based commanders was deafening. Despite excellent on-line fully encrypted teletype-based resources and prepared reports from Pueblo, absolutely no instructions were ever received. . . . Pueblo was, ultimately, alone.”