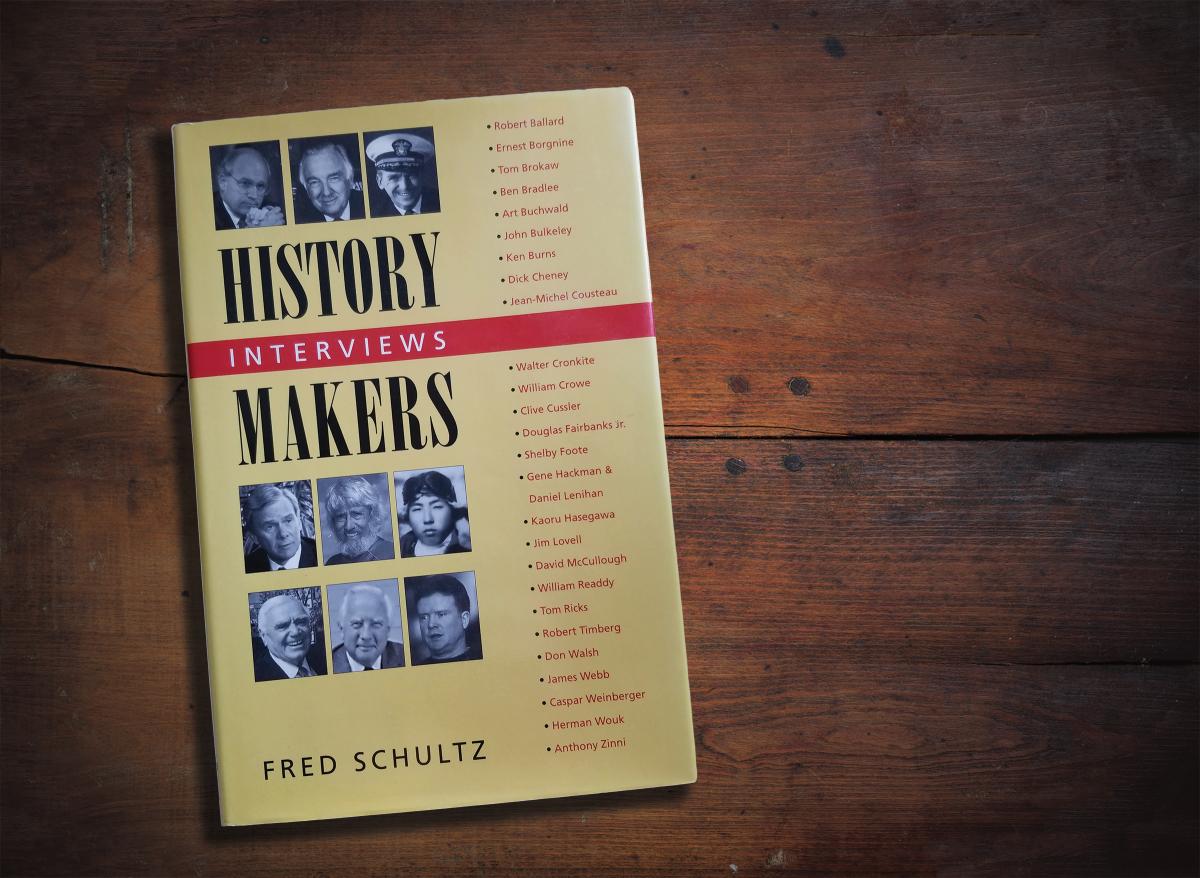

As we concluded Part One of this look back on the 20th anniversary of the Naval Institute Press book History Makers: Interviews, a longtime U.S. Naval Institute member, retired Navy Captain Bill Horn, had called in spring 1995. He wanted to notify me of an extraordinary visit being planned for a wreath-laying at the Navy Memorial in Washington scheduled for 29 July, the 50th anniversary of the last sinking by World War II Japanese aircraft of a U.S. Navy destroyer, the USS Callaghan (DD-792).

A Kamikaze Pilot Who Survived

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

Requesting an invitation to the ceremony was Kaoru Hasegawa, one of a three-man crew from Japanese kamikaze Squadron 12. While attempting to complete a suicide mission east of Okinawa, they were shot down by the Callaghan on 25 May 1945. The destroyer’s crewmen rescued two of the enemy aviators still alive, but only Hasegawa survived. He was transferred to the USS New Mexico (BB-40), and spent the final days of the conflict as a prisoner of war. Now, 50 years later, he wanted to research exactly what happened on “the most important day of my life,” and track down the U.S. veterans who had saved his life.

That is when I met Kaoru Hasegawa at Naval Institute headquarters for an interview titled “Success Meant Death,” which appeared in the October 1995 issue of Naval History. In Japan, he was a well-known businessman, having been the CEO of Rengo Co. Ltd., the largest manufacturer of paper and cardboard containers in the country. Our interview, in Japanese, appeared prominently in the November 1998 Nihon Keizai Shimbun, touted as Japan’s “leading business newspaper,” under the title “My Personal History: Two Lives.”

Following publication of the Naval History interview, the erstwhile kamikaze began hosting annual events in Washington, and my wife and I had a standing invitation. The Hasegawa dinners, as they would soon be known to those in attendance (often including VIPs such as Admirals William Crowe and Elmo Zumwalt), were exquisite affairs, in Washington’s best restaurants; they also grew to be reunions in their own way. We looked forward to seeing old friends again each year. Always in attendance was retired Rear Admiral Bill Thompson (the driving force behind the Navy Memorial in D.C. and whose initials are on the bronze sea bag of the Memorial plaza’s “Lone Sailor” statue). Accompanying him was his wife Dorothy, who invariably saved our seats and had her annual gardening tales to tell us. One year, she actually brought special seeds she had saved so we could plant our own pole beans. Also reliably in attendance was Leo Jarboe, a Callaghan crew member we befriended and who later appeared in one of the first video interviews we did for the Naval Institute’s 65-vignette 2007 documentary film collection, the award-winning Americans at War.

Hasegawa’s generosity was extraordinary, as he had members of his entourage present gifts to all in attendance. During one of the ship’s reunions, a Callaghan crew member presented his former enemy with the wristwatch he was wearing when he was shot down. The following year, Hasegawa presented his new comrade with a jeweled Seiko quartz watch in return.

In 2000, the former kamikaze, who died in January 2004, paid all expenses for Leo Jarboe and the Callaghan's two former executive officers, Jake Heimark (at the time of Hasegawa's rescue) and Buzz Buzzetti (at the time of the ship’s sinking), and their wives for a ten-day trip to Japan. In checking facts for this account, I found that today Hasegawa’s right-hand man at each of these events, Yosuke Kawamoto, is now the Rengo Company’s chief operating officer.

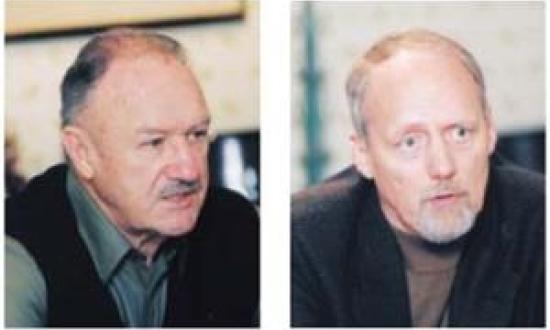

Gene Hackman: Movie Star, Author, Marine

(U.S. Naval Institute David Hofeling)

When I met him in 1999, Gene Hackman was filming The Replacements, starring as football coach Jimmy McGinty, who’d been hired to lead a team of misfits to complete a strike-shortened season in the NFL. It was one of 83 movies in which he appeared over his long film career. I was there to talk about a new Age of Sail novel, Wake of the Perdido Star, he’d cowritten with underwater archaeologist Daniel Lenihan, who had accompanied Hackman on several recreational deep dives to sunken ships and who also was there for our interview.

I had contacted the publisher of the book, and Hackman’s publicist said he could accommodate my request. I would be given 15 minutes with the two coauthors late one Friday afternoon at the Four Seasons hotel in Washington. Given the day and the time, I had asked their publicist whether I could treat them to some refreshment afterward at the hotel lounge. The schedule was much too tight, I was told, so that was out of the question.

While the interview was under way, covering not only the new book, but Hackman’s story of lying about his age to join the Marine Corps and his service in China, the publicist constantly checked the time and gasped when, as we wrapped it up, I asked the Oscar-winning actor and his coauthor if they would like to retreat to the lounge upstairs.

“Sure, absolutely,” Hackman said, and as we started walking up a flight of stairs, he looked at me and said, “You know, Fred, that’s the best interview I’ve ever done.” I asked him how that could be, after all his years in Hollywood. “You actually came prepared for it and had your questions ready. You read the book,” he said. “Last week, I was on the Today show with Katie Couric. When the camera light came on, she said, ‘So, Gene, tell us what your book’s about.’”

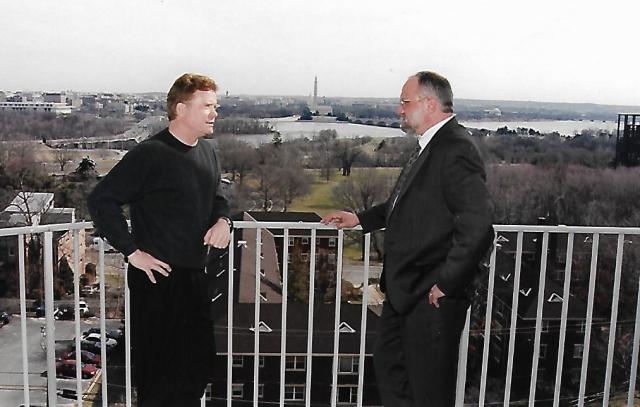

‘A Bit of Hollywood Intrigue’

(U.S. Naval Institute David Hofeling)

These interviews at times led to conversations with several actors with naval connections. But only once did I find myself in the middle of a bit of Hollywood intrigue. When photo editor Dave Hofeling and I arrived to meet former Secretary of the Navy and author James Webb, we immediately were amazed at the striking vista in his sunken Arlington, Virginia, office. From the hillside back entrance, Webb led us down a long flight of stairs to a sitting area with a patio door opening to a view of the Iwo Jima Memorial in the foreground, to the National Mall, past the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, and all the way to the U.S. Capitol. It was a fitting site for someone who had received the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, two Bronze Stars, and two Purple Hearts during the Vietnam War.

While we covered a wide range of topics, a motion picture with Webb’s name on it was about to be released by Paramount Pictures, titled Rules of Engagement, starring Tommy Lee Jones and Samuel L. Jackson and directed by William Friedkin, winner of Academy Awards for The French Connection and The Exorcist. Webb told the whole story of how he had written the screenplay for the movie, but Friedkin had taken liberties with the script and had the Samuel Jackson character murdering a North Vietnamese prisoner to send a message to other prisoners of war he had taken in Vietnam. Webb was so upset that this aspect of the film would sap away any credibility it would have with Marines who would be presumably interested in seeing it that he “took my name off my own movie.”

Our interview appeared in Proceedings in advance of the film’s premiere, and I received a call one morning from the Wall Street Journal, congratulating me for my “scoop,” which I didn’t realize I had. The newspaper had contacted Webb for comment on the movie, wondering why he had no screenplay credit and instead had only “Story by” affixed to his name at the end of the film. When asked by the reporter about the apparent discrepancy, Webb told him to call me for a quote, because I had already unknowingly broken the story in the interview.

The Wall Street Journal piece ran on a Friday, and on Monday, I received a call from director Friedkin at Paramount, asking how we could have published such a scurrilous interview in our publication. I told Editor-in-Chief Fred Rainbow about the call, and he asked me to call Friedkin back and ask him to be our featured speaker at the Naval Institute’s upcoming Annual Meeting. After telling me he’d have to first ask his wife, Paramount’s CEO, Sherry Lansing, he said he’d get back to me. And so, that’s how William Friedkin became our Annual Meeting speaker, beginning that night with “This film is Jim Webb’s story. . . .”

At that time, my Dad had been coming to the Annual Meeting religiously for years as a member, even though he was an Army veteran. I asked Friedkin whether I could bring Dad by the hotel the morning after his speech to meet him, since he had never met a Hollywood director before. Friedkin graciously agreed and told us to come to his room first thing in the morning, because he had a breakfast appointment he couldn’t break. So, we showed up at the prescribed time, and Friedkin could not have been more polite and accommodating, as he discussed the banking business in Los Angeles with my father, a retired banker himself. We eventually followed Friedkin to the front desk to meet his breakfast date, and sitting there in the lobby reading a newspaper was a familiar face. It was Jim Webb.

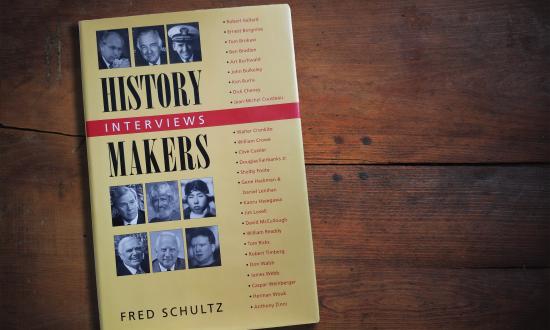

Interviews and the Independent Forum

The title of this two-part look back 20 years since publication of the Naval Institute Press book, History Makers—Interviews, comes from the dust-jacket observation from former Good Morning, America host David Hartman, who captures the essence of the interview as a journalist’s and a historian’s most valuable tool. Direct answers to direct questions are the most unvarnished and reliable means to “the best obtainable version of the truth,” to borrow the mantra of the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward, himself the subject of two Proceedings interviews with me and a frequent panel moderator at Naval Institute events.

Many people have asked how I managed to “land” so many of these interviews with well-known people. The first reaction is always, “I asked.” But it is not quite that simple. Much of the credit for the interviews goes to the Naval Institute itself. Since 1873, it has been an independent forum and has fought hard to keep it that way. I have simply been able to rely on that cachet and gravitas since moving to Annapolis in 1989. Not many people have turned me down, and only a few had a differing view of how independent the organization really is. George Will, the syndicated columnist known for his vast vocabulary, took a phone call during our Proceedings interview, telling the caller that he was “busy being interviewed by the Navy.” Well, not quite.

Great pains have been taken to preserve the organization’s independence, as we touted it has having “no editorial point of view.” And that has turned out to be its calling card when we were in search of the perfect people to write, to be interviewed for publication, to moderate a panel, or to deliver an address.

All this played out clearly at the 1992 Annual Meeting, partially in celebration of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ first voyage to America. We had had a morning panel discussion of differing theories concerning where Columbus actually landed, moderated by William F. Buckley Jr., the conservative commentator, editor of The National Review, and famously accomplished sailor. That afternoon, Woodward served as moderator of a panel on the future of naval operations. A proud former Proceedings author, General Colin Powell, was to deliver the luncheon address that day and was introduced as the current Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

His first words referred directly to the independent forum and summed up what the organization has been all about now for 147 years: “I’d like to begin by saying that I know of nowhere else but the U.S. Naval Institute where a Chairman of the Joint Chiefs could find himself seated at lunch between Bob Woodward and Bill Buckley.”