Hampton Roads, March 14, 1862

My Dear Mother and father,

I commence this now, but I don't know when I shall finish, as I have to write it at odd moments, when I can find a few minutes' rest. When I bid Charley good night on Wednesday the 5th I confidently expected to see you the next day, as I then thought it would be impossible to finish our repairs on Thursday, but the mechanics worked all night, and at 11 A.M. on Thursday we started down the harbor, in company with the gun-boats Sachem and Currituck. We went along very nicely and when we arrived at Governor's Island, the Steamer Seth Low came along side and took us in tow. We went out passed the Narrows with a light wind from the West and very smooth water. The weather continued the same all Thursday night.

I turned out at six o'clock on Friday morning, and from that time until Monday at 7 P.M. I think I lived ten good years. About noon the wind freshened and the sea was quite rough. In the afternoon the sea was breaking over our decks at a great rate, and coming in our hawse pipe forward, in perfect floods. Our berth deck hatch leaked in spite of all we could do, and the water came down under the Tower [turret] like a water fall. It would strike the pilot house and go over the Tower in most beautiful curves. The water came through the narrow eye holes in the pilot house with such force as to knock the helmsman completely round from the wheel.

At 4 P.M. the water had gone down our smoke stacks and blowers to such an extent that the blowers gave out, and the Engine Room was filled with gas. Then Mother occurred a scene I shall never forget. Our Engineers behaved like heroes every one of them. They fought with the gas, endeavoring to get the blowers to work, until they dropped down, apparently as dead as men ever were. I jumped in the Engine Room with my men as soon as I could and carried them on top of the Tower to get fresh air. I was nearly suffocated with the gas myself, but got on deck after every one was out of the Engine Room just in time to save myself. Three firemen were in the same condition as the Engineers. Then times looked rather blue I can assure you.

We had no fear as long as the Engine could be kept going to pump out the water, but when that stopped the water increased rapidly. I immediately rigged the hand pump on the berth deck, but we were obliged to lead the hose out over the Tower, there was not force enough in the pump to throw the water out. Our only resource now was to bail, and that was useless as we had to pass the buckets up through the Tower, which made it a very long operation.

What to do now we did not know. We had done all in our power and must let things take their own course. Fortunately the wind was off shore, so we hailed the tug boat, and told them to steer directly for the shore in order to get in smooth water. After five hours of hard steaming, we got near the land and in smooth water. At 8 P.M. we managed to get the engines to go in everything comparatively quiet again.

The Captain had been up nearly all the previous night, and as we did not like to leave the deck without one of us being there, so I told him I would keep the watch from 8 to 12, he take it from 12 to 4, and I would relieve him from 4 to 8. Well the first watch passed off very nicely, smooth sea, clear sky, the moon out and the old tank going along five and six knots very nicely. All I had to do was to keep awake and think over the narrow escape we had in the afternoon. At 12 o'clock things looked so favorable that I told the Captain he need not turn out, I would lay down with my clothes on, and if anything happened I would turn out and attend to it. He said very well and I went to my room and hoped to get a little nap. I had scarcely got to my bunk when I was startled by the most infernal noise that I ever heard in my life. The Merrimac's firing on Sunday was music to it.

We were just passing a shoal and the sea suddenly became very rough and right ahead. It came up with tremendous force through our anchor well, and forced the air through our hawse pipe where the chain comes and there the water would come through in a perfect stream clear to our berth deck, over the Ward Room table. The noise resembled the death groans of twenty men, and certainly was the most dismal, awful sound I ever heard. Of course the Captain & myself were on our feet in a moment and endeavoring to stop the hawse pipe. We succeeded partially but now the water commenced to come down our blowers again and we feared the same accident that happened in the afternoon.

We tried to hail the Tug Boat, but the wind being directly ahead, they could not hear us and we had no way of signaling to them, as the steam whistle which father recommended had not been put on. We commenced to think then the Monitor would never see day light. We watched carefully every drop of water that went down the blowers, and sent continually to ask the Firemen how the blowers were going. His only answer was slowly, but could not be kept going much longer unless we could stop the water from coming down. The sea was washing completely over our decks and it was dangerous for a man to go on them so we could do nothing to the blowers.

In the midst of all this our wheel ropes jumped off the steering wheel (owing to the pitching of the ship) and became jambed. She now commenced to sheer about at awful rate and we thought our hawser must certainly part. Fortunately it was a new one and held on well. In the course of half an hour we fixed the wheel ropes and now our blowers were the only difficulty. About 3 o'clock on Saturday morning, the sea became a little smoother, though still rough, and going down our blowers to some extent. The never failing answer from the Engine Room, "Blowers going slowly but cant go much longer."

From 4 A.M. till day light, was certainly the longest hour and a half I ever spent. I certainly thought old Sol had stopped in China and never intended to pay us another visit. At last however we could see and made the Tug Boat understand to go nearer in shore and get in smooth water, which we did at about 8 A.M. Things were again a little quiet, but every thing wet and uncomfortable below. The decks and air ports leaked and the water still came down the hatches and under the Tower. I was busy all day, making out my station bills and attending to different things that constantly required my attention. At 3 P.M. we parted our hawser, but fortunately it was quite smooth, and we secured it without difficulty. At 4 P.M. we passed Cape Henry and heard heavy firing in the direction of Fortress Monroe.

As we approached it increased, and we immediately cleared ship for action. When about half way between Fortress Monroe and Cape Henry, we spoke a pilot boat. He told us the Cumberland was sunk and the Congress on fire and had surrendered to the Merrimac. We did not credit it, at first, but as we approached Hampton Roads, we could see the fine old Congress burning brightly, and we knew then it must be so. Sadly indeed did we feel, to think those two fine old vessels had gone to their last homes, with so many of their brave crews. Our hearts were very full, and we vowed vengeance on the "Merrimac," if it should ever be our lot to fall in with her.

At 9 P.M. we anchored near the Frigate Roanoke, the flagship, Captain [John] Marston (the major's brother). Captain Worden immediately went on board and received orders to proceed to New Port News, and protect the Minnesota (which was aground) from the Merrimac. We immediately got underweigh and arrived at the Minnesota at 11 P.M. I went on board in our cutter and asked the Captain what his prospects were of getting off. He said he should try to get afloat at 2 A.M. when it was high water. I asked him if we could render him any assistance, to which he replied No. I then told him we should do all in our power to protect him from the attacks of the Merrimac. He thanked me kindly and wished us success.

Just as I arrived back to the Monitor, the Congress blew up, and certainly a grander sight was never seen, but it went straight to the marrow of our bones. Not a word was said but deep did each man think and wish he was by the side of the Merrimac. At 1 A.M. we anchored near the Minnesota. The Captain and myself remained on deck, waiting for the Merrimac. At 3 A.M. we thought the Minnesota was afloat and coming down on us, so we got underweigh as soon as possible and stood out of the Channel. After backing and filling about for an hour we found we were mistaken and anchored again. At daylight we discovered the Merrimac at anchor with several vessels under Sewall's [sic] Point. We immediately made every preparation for battle.

At 8 A.M. on Sunday the Merrimac got underweigh, accompanied by several Steamers, and started for the Minnesota. When a mile distant she fired two guns at the Minnesota. By this time our anchor was up, the men at quarters, the guns loaded and everything ready for action. As the Merrimac came closer, the Captain passed the word to commence firing. I triced up the port, ran the gun out and fired the first gun, and thus commenced the great battle between the "Monitor" and "Merrimac."

Now mark the condition our men and officers were in. Since Friday morning, 48 hours, they had had no rest, and very little food, as we could not conveniently cook. They had been hard at work all night, and nothing to eat for breakfast except hard bread, and were thoroughly worn out. As for myself, I had not slept a wink for 51 hours, and had been on my feet almost constantly. But after the first gun was fired, we forgot all fatigues, hard work and everything else, and went to work fighting as hard as men ever fought.

We loaded and fired as fast as we could. I pointed and fired the guns myself. Every shot I would ask the Captain the effect, and the majority of them were encouraging. The Captain was in the Pilot House directing the movements of the vessel. Acting Master [Louis] Stodder was stationed at the wheel which turns the Tower, but as he could not manage it, he was relieved by [Chief Engineer Alban C.] Stimers. The speaking trumpet from the Tower to the pilot House was broken, so we passed the word from the Captain to myself on the berth deck, by Pay Master [William] Keeler and Captain's Clerk Toffy [Daniel Toffey].

Five times during the engagement we touched each other, and each time I fired a gun at her, and I will vouch the 168 lbs. penetrated her sides. Once she tried to run us down with her iron prow, but did no damage whatsoever. After fighting for two hours, we hauled off for half an hour to hoist shot in the Tower. At it we went again as hard as we could. The Shot, Shell, grape, canister, musket and rifle balls flew about us in every direction, but did us no damage. Our Tower was struck several times, and though the noise was pretty loud, it did not effect us any. Stodder and one of the men were carelessly leaning against the Tower, when a shot struck the Tower exactly opposite to them, and disabled them for an hour or two.

At about 11:30 the Captain sent for me. I went forward, and there stood as noble a man as lives, at the foot of the ladder of the pilot house. His face was perfectly black with powder and iron, and he was apparently perfectly blind. I asked him what was the matter. He said a shot had struck the Pilot House exactly opposite his eyes and blinded him, and he thought the Pilot House was damaged. He told me to take charge of the ship and use my own descretion. I lead him to his room and laid him on the sofa, and then took his position. On examining the Pilot house I found the iron hatch on top, had been knocked about half way off, and the second iron log from the top, on the forward side was completely cracked through. We still continued firing, the Tower being under the direction of Stimers.

We were between two fires. The Minnesota on one side and the Merrimac on the other. The latter was retreating to Sewall's Point and the Minnesota had struck us twice on the Tower. I knew if another shot should strike our pilot house in the same place, our steering apparatus would be disabled and we should be at the mercy of the Batteries on Sewall's Point. The Merrimac was retreating towards the latter place. We had strict orders to act on the defensive and protect the Minnesota. We had evidently finished the Merrimac as far as the Minnesota was concerned, our pilot house was damaged and we had strict orders, not to follow the Merrimac; therefore, after the Merrimac had retreated, I went to the Minnesota and remained by her until she was afloat. Genl. [John] Wool and Secretary [Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus] Fox both have complimented me very highly for acting as I did, and said it was the strict military plan to follow. This is the reason we did not sink the Merrimac, and every one here capable of judging says we acted exactly right.

The fight was over now, and we were victorious. My men and myself were perfectly black with smoke and powder. All my under clothes were perfectly black and my person was in the same condition. As we ran along side the Minnesota, Secretary Fox hailed us, and told us we had fought the greatest naval battle on record and behaved as gallantly as men could. He saw the whole fight. I felt proud and happy then Mother, and felt fully repaid for all I had suffered. When our noble Captain heard the Merrimac had retreated, he said he was perfectly happy and willing to die, since he had saved the Minnesota. Oh, how I love and venerate that man. Most fortunately for him his most intimate class mate and friend, Lieut. [Henry A.] Wise saw the fight and was along side immediately after the Engagement. He took him on board the Baltimore boat and carried him to Washington that night.

The Minnesota was still aground and we stood by her until she floated about 4 P.M. She grounded again shortly and we anchored for the night. I was now Captain and 1st Lieutenant and had not a soul to help me in the ship as Stodder was injured and [Acting Master John] Webber useless. I had been up so long, had had so little rest and been under such a state of excitement, that my nervous system was completely run down. Every bone in my body ached, my limbs and joints were so sore that I could not stand. My nerves and muscles twitched as though electric shocks were continually passing through them and my head ached as if it would burst. Some times I thought my brain would come right out over my eye brows. I laid down and tried to sleep, but I might as well have tried to fly.

About 12 o'clock, Acting Lieutenant [William] Flye came on board and reported to me for duty. He lived in Topsham, opposite Brunswick, and recollects father very well. He immediately assumed the duties of 1st Lieut. and I felt considerably relieved. But no sleep did I get that night owing to my excitement. The next morning at 8 o'clock we got underweigh, and stood through our fleet. Cheer after cheer went up from the Frigates and small craft for the glorious little Monitor, and happy indeed did we all feel. I was Captain then of the vessel that had saved New Port News, Hampton Roads, Fortress Monroe (as Genl. Wool himself said) and perhaps your Northern Ports. I am unable to express the happiness and joy I felt to think I had served my country and Flag so well, at such an important time. I passed Lieutenant [Norman von Heldreich] Farquhar's vessel and answered his welcome salute. About 10 a.m. Genl. Wool and Mr. Fox came on board and congratulated us upon our victory, etc. We have a standing invitation from Genl. Wool to dine with him, but no officer is allowed to leave the ship until we sink the Merrimac. At 8 o'clock that night, [Lieutenant] Tom Selfridge came on board and took command and brought the following letter from Fox to me.

Old Point, March 10th

My Dear Mr. Greene,

Under the extraordinary circumstances of the contest of yesterday, and the responsibility devolving upon me and your extreme youth, I have suggested to Captain Marston, to send on board the Monitor as temporary Commanding Lt. Selfridge, until the arrival of Commodore Goldsborough, which will be in a few days. I appreciate your position and you must appreciate mine, and serve with the same zeal and fidelity. With kindest wishes for you all.

G. A. Fox.

Of course I was a little taken aback at first, but (soon saw the) on a second thought, I saw it was as it should be. You must recollect the immense responsibility resting upon this vessel. We literally hold all the property, ashore and afloat in these regions, as the wooden vessels are useless against the Merrimac. At no time during the war, either in the Navy or Army, has any one position been so important as this vessel. You may think I am exaggerating some what, because I am in the Monitor, but the President, Secretary, Genl. Wool all think the same, and have telegraphed to that effect, for us to be vigilant, etc.

The Captain receives every day numbers of anonymous letters from all parts of the Country, suggesting plans to him etc. and I think some people North of Mason and Dixon's line have a little fear of the Merrimac. Under these circumstances it was perfectly right and proper in Mr. Fox to relieve me from the command, for you must recollect I had never performed any but midshipman's duty before this: but between you and me, I would have kept the command with all its responsibility, if I had my choice, and either the Merrimac or the Monitor should have gone down in the next engagement. But then you know all young people are vain, conceited and without judgment. Even the President telegraphed to Mr. Fox to do so and so. Mr. President, I suppose thinking Mr. Fox rather young, he being only about 40. Mr. Fox however, had already done what the President telegraphed to him several hours before.

Selfridge was only in command two days until Lt. [William] Jeffers arrived from Roanoke Island. Mr. Jeffers is everything desirable. Talented, educated, energetic and experienced in Battle. Well I believe I have about finished. Buttsy [First Lieutenant Walter R. Butt], my old room mate was on board the Merrimac: little did we ever think at the Academy, we should be firing 150 lbs. shot at each other, but so goes the World. Our pilot house is nearly completed. We have now solid oak, extending from three inches below the eye holes in the Pilot House, to five feet out on the deck. This makes an angle of 27 degrees from the horizontal. This is to be covered with 3 inches of iron. It looks exactly like a pyramid. We will now be invulnerable at every point. The deepest indentation on our sides was 4 inches. Tower 2 inches and deck 1/2 inch. We were not at all damaged except the Pilot House. No one was affected by the concussion in the Tower, either by our own guns or the shot of the Enemy. This a pretty long letter for me, for you recollect my writing abilities. With much love to you all I remain your aff. son & brother,

'To Remedy a Wrong'

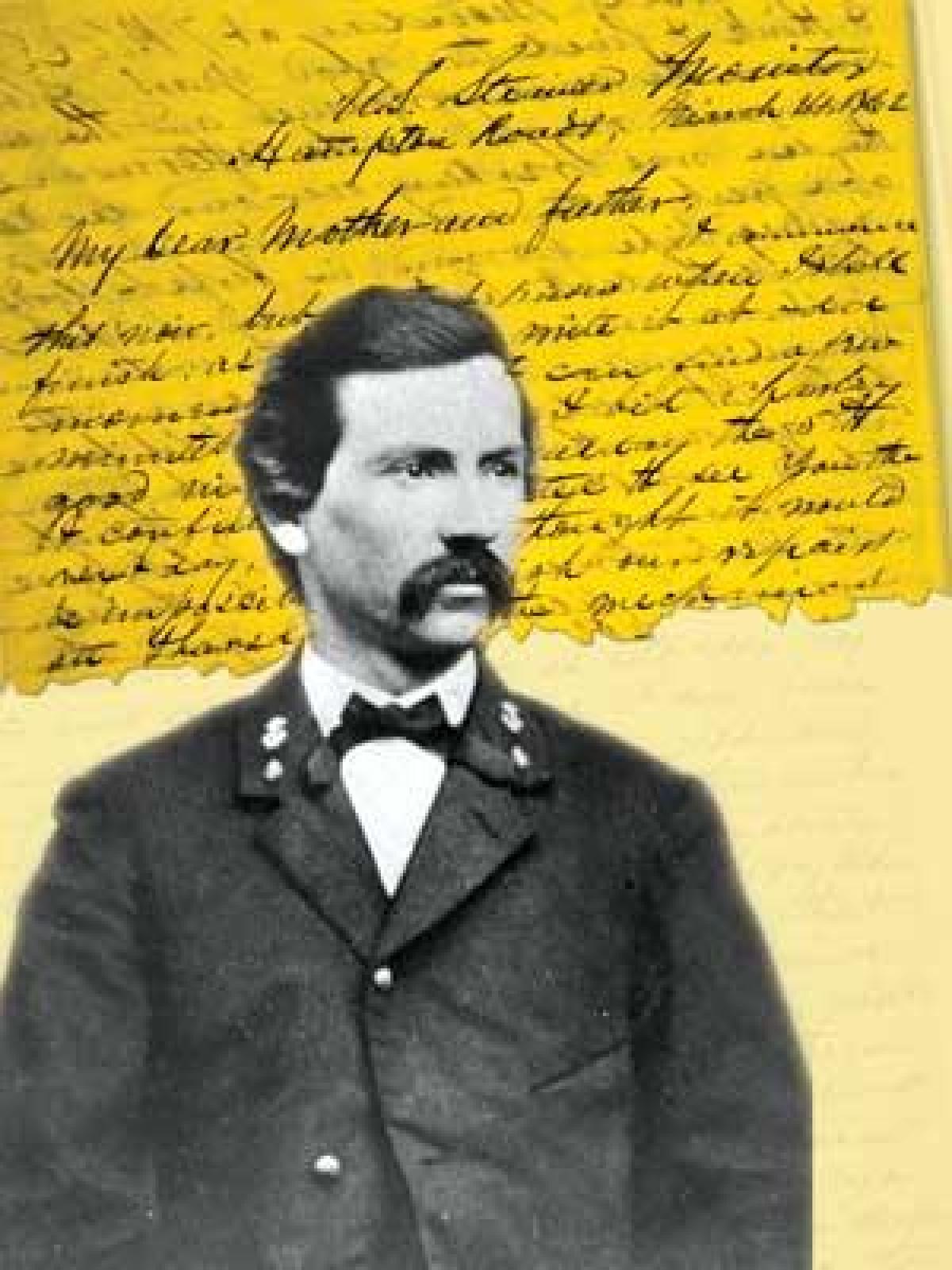

Almost three years after the end of the Civil War, Captain (later Rear Admiral) John L. Worden (pronounced WERE-den), commanding officer of the USS Monitor in the Battle of Hampton Roads, wrote the following letter to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Worden aimed to set the record straight for then-Lieutenant Commander Samuel Dana Greene, who had been living under a dark cloud for not pursuing the CSS Virginia after he assumed command of the Monitor from the wounded Worden. The latter had never filed an official report with the Navy and thus never officially condoned the actions of his subordinate. Since his death in 1897, the Navy has named four ships after Worden, a founding member of Naval History's parent organization, the U.S. Naval Institute. This letter appeared in the February 1927 issue of the Institute's Proceedings magazine.

Sir: Recently learning that Lieutenant-Commander S. D. Greene, the executive officer of the Monitor in her conflict with the Merrimack in Hampton Roads, on the ninth of March 1862, has been annoyed by ungenerous allusions to the fact that no official record existed at the Department, in relation to my opinion of his conduct on that occasion, I desire now to remedy a wrong, which I regret should so long have existed, and to do justice to that gallant and excellent officer, as well as to all the officers and crew of the Monitor, who, without exception, did their duty so nobly in that remarkable encounter, by placing on the files of the Department the following report.

In order to do full justice to him and to the others under my command, I beg leave to state narratively the prominent points in the history of that vessel from the date of my orders to her, until the encounter with the Merrimack. . . .

Soon after reaching my vessel and at about 7:30 o'clock a.m. the Merrimack was observed to be underway, accompanied by her consorts, steaming slowly. I got underway as soon as possible and stood directly for her, with crew at quarters, in order to meet and engage her as far away from the Minnesota as possible. As I approached the enemy, her wooden consorts turned and stood back in the direction from which they had come, and she turned her head up stream, against the tide, remaining nearly stationary, and commenced firing. At this time, about 8 o'clock a.m. I was approaching her on her starboard bow, on a course nearly at right angles with her line of keel, reserving my fire until near enough that every shot might take effect. I continued to so approach until within very short range, when I altered my course parallel with hers, but with bows in opposite directions, stopped the engine and commenced firing. In this way I passed slowly by her, within a few yards, delivering fire as rapidly as possible, and receiving from her a rapid fire in return, both from her great guns and musketry, the latter aimed at the pilot house, hoping undoubtedly to penetrate it through the lookout holes and to disable the commanding officer and helmsmen. At this period I felt some anxiety about the turret machinery, it having been predicted by many persons, that a heavy shot with great initial velocity striking the turret, would so derange it as to stop its working, but finding that it had been twice struck and still revolved as freely as ever, I turned back with renewed confidence and hope and continued the engagement at close quarters, every shot from our guns taking effect upon the huge sides of our adversary, stripping off the iron freely. Once, during the engagement, I ran across and close to her stern, hoping to disable her screw, which I could not have missed by more than two feet. Once, after having passed upon her port side, in crossing her bow to get between her and the Minnesota again, she steamed up quickly and finding that she would strike my vessel with her prow or ram, I put the helm "hard a port" giving a broad sheer, with our bow towards the enemy's stern, thus avoiding a direct blow and receiving it at a sharp angle on the starboard quarter, which caused it to glance without inflicting any injury. The contest so continued except for an interval of about fifteen minutes when I hauled off to remedy some deficiency in the supply of shot in the turret, until near noon, when being within ten yards of the enemy a shell from her struck the pilot house near the lookout hole, through which I was looking, and exploded, fracturing one of the "logs" of iron of which it was composed, filling my face and eyes with powder utterly blinding and in a degree stunning me. The top of the pilot house too, was partially lifted off by the force of the concussion which let in a flood of light, so strong as to be apparent to me, blind as I was, and caused me to believe that the pilot house was seriously disabled. I therefore gave orders to put the helm to starboard and sheer off and sent for Lieutenant Greene and directed him to take command. I was then taken to my quarters and had been there but a short time when it was reported to me that the Merrimack was retiring in the direction of Norfolk. In the meantime Lieutenant Greene, after taking his place in the pilot house and finding the injuries there less serious than I supposed, had turned the vessel's head again in the direction of the enemy, to continue the engagement, but before he could get at close quarters with her, she retired. He therefore very properly returned to the Minnesota and lay by her until she floated.

The Merrimack having been thus checked in her career of destruction, and driven back crippled and discomfited, the question arises should she have been followed in her retreat to Norfolk? That such course would commend itself very temptingly to the gallantry of an officer and be difficult to resist, is undeniable; yet I am convinced that under the condition of affairs then existing at Hampton Roads, and the great interests at stake there, all of which were entirely dependent upon the Monitor, good judgment and sound discretion forbade it. It must be remembered that the pilot house of the Monitor was situated well forward in her bows and that it was quite considerably damaged. In following in the wake of the enemy, it would have been necessary, in order to fire clear of the pilot house, to have made broad "yaws" to starboard or port, involving in the excitement of such a chase, the very serious danger of grounding in the narrower portions of the channel and near some of the enemy's batteries, whence it would have been very difficult to extricate her, possibly involving her loss. Such a danger her commanding officer would not, in my judgment, have been justified in encountering, for her loss would have left the vital interests in all the waters of the Chesapeake at the mercy of future attacks from the Merrimack. Had there been another ironclad in reserve at that point, to guard those interests, the question would have presented a different aspect, which would not only have justified him in following, but perhaps made it his imperative duty to do so.

Captain

Hon. Gideon Welles,

Secretary of the Navy,

Washington, D.C.