Editor’s Note: The author will be a panel participant in the U.S. Naval Institute’s “Lessons of Heroism: The Vietnam War POW Experience,” being presented at the U.S. Naval Institute’s Jack C. Taylor Conference Center on Thursday, 23 March, at 1030, as well as on live-stream. For more information and to register, click here.

The Navy commander who shows up at Sybil Stockdale’s front door in May of 1965 is a baby-faced redhead with a mustache. His uniform does not fit well over his pudgy frame. An hour late, he saunters into Sybil’s living room, removes his military cover, or hat, working the room like a politician running for office. A public information officer, he seems to relish his role as Navy spokesman for the aviation community.

As the wife of the air group commander on board the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CVA-34), Sybil is responsible for mentoring the wives of the men who work for her husband, Navy Commander James Stockdale. She takes her role seriously, and even more so when the men are deployed. They have been gone for several weeks, but the ladies and their children are facing months of separation. Sybil has invited this naval officer because she has heard he has useful things to say about what to do if anything happens to naval aviators deployed to Southeast Asia.

“What I am about to discuss with you today should not be discussed with others,” the commander intones. In unison, the ladies lean forward. Be prepared, he tells the women, for the possibility that your men could become captives of enemy forces in Vietnam. Ticking off the rules of engagement, he says, “In the event your husband is captured, every effort will be made to notify the next of kin personally.”

“Next of kin”—the official term for wives, parents, and children. “They should be warned not to release any information about the prisoner and not to be interviewed by the press concerning his background.”

Married to a senior officer on his fifth deployment to the Western Pacific, Sybil has never heard a talk like this. She looks around at the spellbound audience. Plates of food are balanced on laps, but no one seems to have eaten a bite. Sybil thinks to herself, “How dreadful it would be if any of them had to face such a possibility.”

He continues, “The standard answer to all news agencies should be ‘Mrs. _________________ has no comment for the press at this time.’” Next of kin should not talk to the media, he insists. What’s more, a wife should not acknowledge to anyone but family that her husband is a prisoner. “Prisoners at present are being well treated, and authorities have every reason to believe that this condition will continue.” He warns that this is only true if the next of kin abide by these rules. “Any information other than name, rank, serial number, and age can be skillfully used in psychological warfare to coerce the prisoner to aid the Communist propaganda program.”

Next of kin must let professionals do their work. “Families are strongly urged not to intercede on behalf of the prisoner without State Department approval. Independent intercession on the part of the individual could seriously damage negotiation being conducted on behalf of the prisoner by the State Department.”

The commander waits for what he has shared to sink in. Sybil doubts he has ever had this much attention from a roomful of women. She cringes when he adds, “If this happens to you, you cry on my shoulder and tell me your troubles.” He seems to have styled himself as a veritable comforter-in-chief.

The women should not expect the worst if their husbands are taken prisoner. Navy Lieutenant (junior grade) Everett Alvarez and Navy Lieutenant Robert Shumaker, two American aviators, have been shot down and captured. The commander believes that the men are being humanely treated.

He passes around photos released by the North Vietnamese of Lieutenants Alvarez and Shumaker and a letter Lieutenant Alvarez wrote to his wife.

Sybil tries cutting him off, but he waxes on about how much Mrs. Alvarez and Mrs. Shumaker rely on him. Later, in one of his lengthy letters, Sybil’s husband Jim cautions Sybil: “Captain Connelly has had some unpleasant experience with [this commander]—has twice told me to tell you to give him a wide berth.” If only she had been given that piece of advice earlier.

After two hours, the commander leaves, and the party breaks up. A few wives linger, peppering Sybil with questions they did not feel comfortable asking the chubby commander. One, barely out of her teens, shakily asks, “You know, Mrs. Stockdale, we haven’t been married very long and I don’t know much about these things. Do you think there’s anything to be afraid of?” Sybil quashes the girl’s fear: “Oh heavens, no. My husband’s been flying for years, and I’ve never heard anything like this before. Don’t give it another thought. I’m sure they’ll all come home safely.”

But, of course, many of them did not come home safely—at least not for a long time. Sybil’s husband is one of them. Jim is shot down and captured four months later.

And the commander’s reassurance that the captives are being well treated is false. They are being tortured, isolated, and denied food and medical treatment. And, a year later, the men are put on parade, a parade of assault and humiliation by the Vietnamese people. The spectacle comes to be known as the Hanoi March.

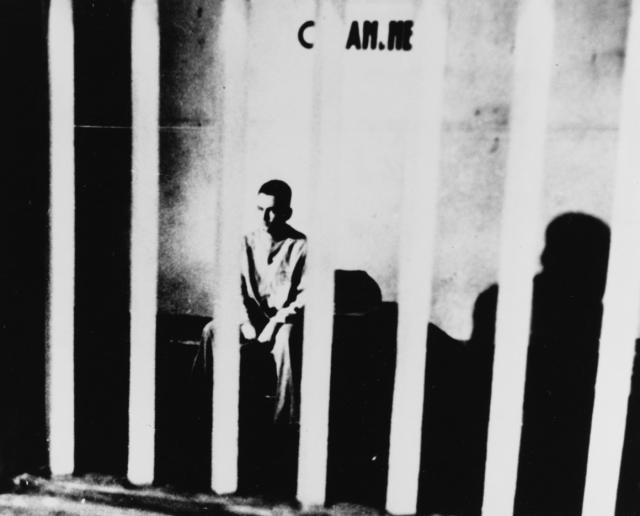

On that sultry evening, the light casts an eerie sheen over the pale and gaunt American POWs. Handcuffed and blindfolded, the men walk like zombies in the twilight. It is 6 July 1966, and they have been told they are going to meet the Vietnamese people. After being piled into trucks, they are herded into a stadium before heading out. In the glare of television cameras, they shuffle solemnly in pairs through the streets of Hanoi.

In numbered prison pajamas and sandals, 52 of them walk a gauntlet of thousands of angry North Vietnamese. The first two Americans greeted by the frenzied mob are Air Force Captain Alan Brudno and Navy Lieutenant Bill Tschudy. The crowd jeers, jabbing with sticks at the Americans clad in prison garb. Some are beaten to the ground. The North Vietnamese crowd begins hurling bottles while the guards stand by, doing nothing to ensure the safety of their prisoners.

The mob presses closer until there is little room for the captives to maneuver. Then the unbridled anger of the crowd reaches a crescendo as they break noses, smash teeth, spit, and punch the Americans. The POWs endure an all-out assault on their bodies and their dignity.

Watching the scene unfold on television from the duplex she calls home on the Yokota Air Base outside Tokyo, Pat Mearns is transfixed and terrified. The grainy black-and-white footage shot by foreign correspondents that night is gruesome. Pat winces as the wrathful horde taunts and heckles the U.S. Navy and Air Force aviators, pelting them with stones, bricks, and trash. Many of the men are bleeding. Others are able to duck the onslaught of projectiles. Pat scours the crowd, searching for the faces of men she knows from her husband’s squadron. Her eyes squint at the TV set until there is a flicker of recognition.

Leaning in to the television, she recognizes Major Neal Jones! Then, Major Larry Guarino, and finally, Captain Quincy Collins, all members of her husband’s 80th Tactical Flight Squadron. One week ago, Jones’s F-105 Thunderchief fighter-bomber reportedly was shot down. Though relieved to see him alive, Pat finds the spectacle shocking. Although Hanoi is more than 2,200 miles from the Yokota Air Base, it makes Pat feel vulnerable. The POWs are fellow Americans and military aviators just like her husband, Major Arthur S. Mearns.

She has never witnessed anything like this, and it fills her with dread. “The men were paraded like targets,” she remembers. “It was unfair and completely against the Geneva Convention.”

But the North Vietnamese are seeking publicity. Calling the aviators “air pirates,” they want to show the world their people are being victimized by the U.S. bombing of North Vietnam. They vow to put the men on trial for war crimes against the people of North Vietnam. War crimes? The word reverberates like a shock wave.

Hanoi does not accept that the men are POWs, as there has been no formal declaration of war between the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and the United States. The previous year, the Viet Cong had executed three American captives, in reprisal for a public execution by the South Vietnamese government of a Communist terrorist. The Geneva Convention of 1949, which governs the treatment of POWs and guarantees their humanitarian treatment, was signed by the DRV. But American diplomats feel it is[TK1] being disregarded.

The Vietnamese people in Hanoi are enraged by the relentless bombing campaign, known as Operation Rolling Thunder, which has been intensifying: 79,000 sorties in 1966, up from 25,000 in 1965. Casualties in North Vietnam are mounting, with estimates of up to 2,000 per month in the spring of 1966. Rage fuels the crowd’s hostility toward the POWs. They want revenge. North Vietnamese leadership is capturing their wrath on film, hoping to engender international empathy and support for North Vietnam and its besieged population.

The plan backfires. Worldwide media coverage of the zombie “parade” and violent attacks on defenseless captives spark outrage. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) reminds Hanoi of their obligation to abide by the Geneva Convention. Prime Ministers Indira Gandhi of India and Harold Wilson of Great Britain appeal to Moscow to restrain North Vietnam. Pope Paul VI, the World Council of Churches, and the United Nations secretary general denounce Hanoi’s plan to hold war crimes trials. Eighteen U.S. senators make a “plea for sanity” to North Vietnam, warning that violence against American POWs “would incite a public demand for retaliation swift and sure.”

Secretary of State Dean Rusk issues a flurry of diplomatic cables to U.S. embassies in Seoul, Tokyo, Taipei, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Vientiane, Colombo, Saigon, Kuala Lumpur, Manila, Rangoon, Singapore, and Bangkok, directing them to warn Hanoi not to follow through on their threats. Although he considered Vietnam “a losing horse” as early as 1961, Rusk has nonetheless supported the commitment of ground troops in South Vietnam, a place he views as inextricably linked to the security of Southeast Asia. In his opinion, “the die for American commitment to Southeast Asia was cast in 1955” when both the United States and South Vietnam signed the SEATO treaty, a pact committing its signatories to defending the region from communism.

Rusk argues in his cable that “substantive violations of the 1949 Geneva Convention by North Vietnam make fair trials impossible. In particular, North Vietnam has failed to comply with the most fundamental procedural safeguards established by the Convention. It has refused to identify the POWs under its control; to allow the ICRC to visit prisoners and to investigate conditions under which they are held; to allow any neutral state to act as protecting power to safeguard prisoners’ interests; and it has ignored the request of the ICRC to assume humanitarian functions normally performed by a protecting power. It has also paraded prisoners through streets filled with excited mobs in violation of Article 13, which states that prisoners ‘must at all times be humanely treated.’”

It is the most pointed diplomatic effort made on behalf of the POWs to date. International condemnation of Hanoi follows. The government of North Vietnam takes note.

Three weeks later, Ho Chi Minh’s public posturing shifts significantly. Notably, he omits the term “war criminals” from his cables to U.S. antiwar activists. On 22 July, a French war correspondent in Hanoi reports that war crimes trials have been postponed. In response to an inquiry from a CBS reporter, Ho Chi Minh states, “No trial [is] in view.” While U.S. officials are relieved, they admit they “are by no means out of the woods.” Hanoi still refuses to accept responsibility for the POWs as required by the Geneva Convention.

The incident demonstrates that the North Vietnamese are sensitive to world opinion. But it takes another three years for the U.S. government to formally change its Keep Quiet policy.

On a Monday morning in May 1969, Sybil Stockdale is getting her kids ready for school when the phone rings. A Pentagon secretary asks her to hold the line. Impatiently, she checks her watch. Dick Capen and Frank Sieverts are on the other end, and they sound elated.

Capen, a former naval officer and publisher for Copley Press in San Diego, is a 35-year-old political appointee recruited by President Richard Nixon’s new Secretary of Defense to work on the POW issue. Sieverts is Capen’s counterpart at the State Department.

“We wanted you to know that here in Washington, in just a few minutes, the Secretary of Defense is going to do the thing you’ve been wanting him to do for so long. He’s going to publicly denounce the North Vietnamese for their treatment of our American prisoners and for their violation of the Geneva Convention. We know you’ve been working long and hard for this day, and we wanted you to be the first to know.”

Three years earlier, Sybil had first raised her voice in protest to the government. It was a lonely task: Government leadership had been almost mute on the topic. Few others had spoken publicly about the issue—much less protested vehemently. Until now, the vexing POW and MIA issue had been the sole purview of the State Department. Back in 1966, President Johnson chose Ambassador Averell Harriman as his point man. Harriman was old school. A seasoned diplomat and politician, he had been tapped repeatedly since World War II to manage thorny foreign policy issues. Surely, he could find a diplomatic solution to the growing number of POWs. Although in his seventies, his energy was legendary, even if he was hard of hearing.

Harriman preferred working behind the scenes, in a “diplomat-to-diplomat” style, using familiar “quiet diplomacy” to negotiate with the North Vietnamese for better treatment and an early release for American captives. Sybil met Harriman in 1966 and 1967, pleading with him to do more, to publicly rebuke the North Vietnamese for mistreatment of the POWs. “When I sharpened the tone of my questions with Ambassador Harriman, he didn’t appear to pay any attention. It was almost as if he were giving a monologue.” Patronizingly, Harriman assures her that the State Department’s efforts on behalf of her husband are extensive, but classified. The women and their families need to trust him and to keep quiet, he said. Harriman’s callous rebuffs leave Sybil feeling helpless and irritable.

But a new administration has brought a new Secretary of Defense: Melvin Laird. He is determined to change the status quo. As a member of Congress, Laird met with several POW and MIA wives. He heard their anguish firsthand. With more than 1,000 men missing or captive in Southeast Asia, Laird had become disillusioned with the State Department’s strategy to solve the vexing POW issue. He was convinced that the Defense Department must take on a stronger advocacy role for the POWs—and a more public one.

He believed the POWs had become the unmentionables. Harriman’s “quiet diplomacy” had been an abject failure. Laird scratched his head at Harriman’s reticence to challenge the enemy’s specious claims of humane prisoner treatment. Harriman’s strategy had not allowed a steady flow of mail, had not enabled neutral inspectors into Hanoi’s prison camps, and had not accounted for the missing. The North Vietnamese were winning the war of propaganda and felt no pressure to abide by the Geneva Convention. The wives in Sybil’s group knew it. Their long-simmering wrath and impatience burst forth at family briefings that Capen and Sieverts held around the country in the spring of 1969.

They protested the government’s inaction—loudly. At a meeting in San Diego, one wife smashed a painting to symbolize what she thought of the Air Force’s commitment to take care of its people. Sybil was dismayed. “Our government still had no reason to believe that keeping quiet was not the best way to proceed and still hoped our men were being treated humanely. I marveled at the detached, casual attitude. . . .”

(Department of Defense)

Why not call out the North Vietnamese on their violations of the Geneva Convention? They could then be held responsible in the court of public opinion. Laird advises the State Department that quiet diplomacy from the Pentagon will be discarded for a new strategy called “Go Public.” And, in shaking up the status quo, he hopes to turn the POW and MIA wives into allies.

Rumors of Laird’s impending policy change fire up Ambassador Harriman. Making a rare trip across the Potomac to the Pentagon, he spends nearly an hour trying to persuade Laird to stay the course and keep quiet. Laird is aware that President Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, also want him to back down. All three are afraid that adding POWs in the mix at the negotiating table will make diplomatic efforts more difficult. Kissinger later says: “I probably thought that to make too big a public issue [of the POWs] weakened us; it didn’t strengthen us.” But Laird is unwavering. The policy must change. Exposing mistreatment and torture will produce a different outcome at the Paris peace negotiations. In the process, it might shame Hanoi into better treatment of the men.

Laird asks Capen to review intelligence about treatment of American prisoners and build his case for a change in policy. Capen consults sources at the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Office of Naval Intelligence, the National Security Agency, and the Central Intelligence Agency.

The findings Capen presents to Laird and the Secretary’s executive team are grim. Evidence of torture, starvation, lack of medical treatment, solitary confinement, and beatings were buried in documents tucked away in file cabinets. Harriman’s diktat to remain quiet and his fear of upsetting the stagnant peace negotiations in Paris prevented the three-letter intelligence agencies from disclosure.

Laird is horrified: “By God, we’re going to go public.”

Scheduling a press conference for 19 May 1969, he and Capen and their staff scramble to develop a comprehensive publicity campaign that will engage the press corps, American Red Cross, United Nations, foreign leaders, the American people, and POW and MIA families. This is a chance to wrest control of an issue that, so far, has been managed by the enemy.

Over the objections of Harriman and Kissinger, and with no endorsement from President Nixon, Laird strides into the Pentagon briefing room. “Good morning, ladies and gentlemen.” Reporters, expecting a low-level official, are surprised. Small chat ceases as all eyes turn to the new Secretary of Defense.

Laird gets right to the point: “The North Vietnamese have claimed that they are treating our men humanely. I am distressed by the fact that there is clear evidence that this is not the case.” The announcement is a departure from the previous five years. This is not the usual bland assurance the media is used to hearing.

Laird states that some American POWs have been held longer in this conflict than any during World War II or the Korean War.

Behind the Secretary of Defense there are posters with statistics about prisoners and missing men. Laird outlines the list of Geneva Convention rules that the North Vietnamese have violated: refusal to deliver mail to prisoners, denial of independent inspections of the prison camps, the use of the prisoners in propaganda films, and failure to provide a comprehensive list of those being held. That must change, he insists. The press corps takes notice.

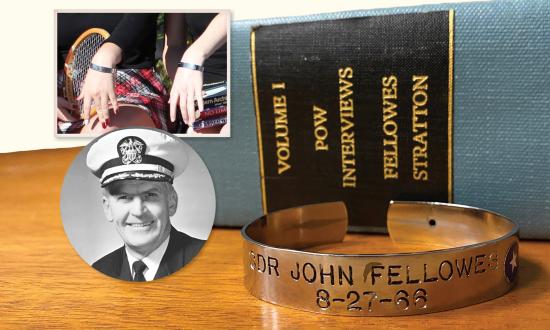

Capen is up next, providing excruciating detail about the torture American POWs have endured. Reporters hang on his every word. Capen passes out dozens of still photos obtained in North Vietnam of haggard, malnourished U.S. prisoners, some with untreated wounds.

Laird’s press conference infuses Sybil with hope. The lobbying of the past few months has paid off. “One military official in the Defense Department told me that they knew they’d better join us, or we were going to mop up the floor with them.”

The event receives only modest media coverage, but the Go Public message is heard in Paris and in Hanoi. North Vietnamese chief negotiator, Xuan Thuy, responds by announcing that his government will never reveal a list of prisoners “as long as the United States does not cease its war of aggression and withdraw its troops from Vietnam.”

Although dug in, Hanoi nonetheless has a new problem. Its aggressive propaganda campaign will now, finally, be matched by the U.S. government.