“Stopped into a church/ I passed along the way/ Well, I got down on my knees/ And I pretend to pray/ You know the preacher likes the cold/ He knows I’m gonna stay.” Popular legend has it those lyrics to the 1965 Mamas and the Papas single “California Dreamin’,” written by “Papa” John Phillips, were inspired by his plebe summer experience at the U.S. Naval Academy during the hot month of August 1954. Holding an appointment to the Class of 1958, Phillips resigned shortly before the academic year began that fall, before assuming a more agreeable beatnik lifestyle playing music in New York’s Greenwich Village. Although unsubstantiated, one myth holds that Phillips’ mandatory attendance at the service in the chapel he “passed along the way” down the Naval Academy’s prominent Stribling Walk each Sunday inspired the storied song’s lyrics about the nature of forced religion.

By 1972, that longstanding Academy requirement of mandatory chapel attendance had been eliminated—bringing to a close the history of the sometimes rocky relationship between midshipmen’s education and the practice of faith.

‘Vital Importance of Good Moral Character’

In a February 1915 circular letter to midshipmen parents, Superintendent William F. Fullam wrote of the singular and constant mission of the chaplain and religious services to “realize the vital importance of good moral character and of upright Christian manhood.” Emphasizing the Academy chapel’s nonsectarian character and the “practically voluntary” nature of the Sunday morning service, the Superintendent wrote that the academy ministry’s “influence and teachings have a direct and practical bearing on the moral and professional conduct and duties of midshipmen both before and after and graduation” and concluded that attendance remained in “the best interest of the midshipmen in every respect.”1

While allowing select midshipmen to attend Annapolis churches by parental request, regulations issued the following year, while not explicitly stating the fact, implicitly ended conscientious excusals from all Sunday morning divine services, by requiring the attendance of all students at either the Academy chapel or a local Annapolis church by parental request.2 The 1928 academy regulations enshrined the mandate in no uncertain terms, stating, “Each and every midshipman is required to attend church on Sundays at the Naval Academy chapel or at one of the regularly established churches in the city of Annapolis.”3

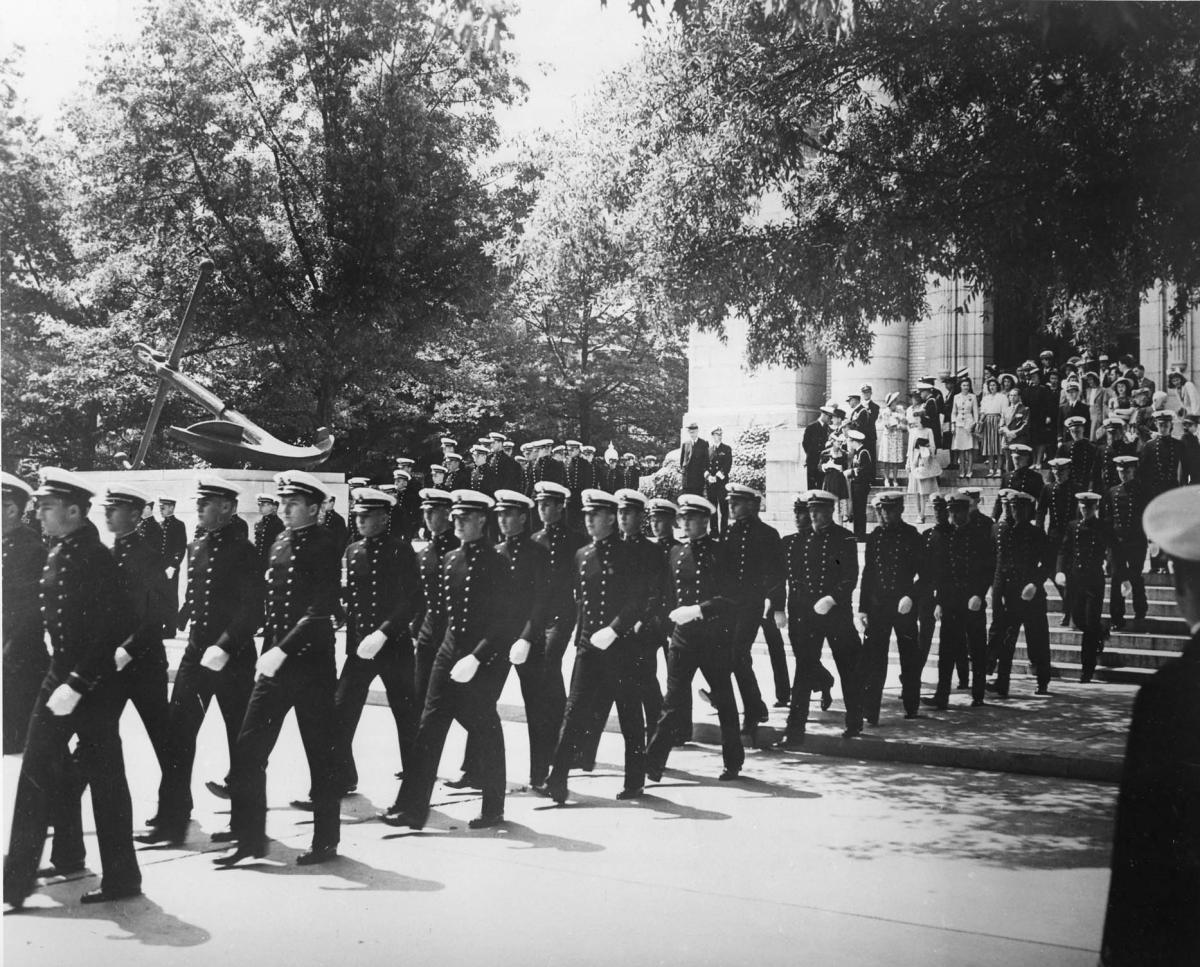

(Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library, USNA)

The new policy met untiring resistance from members of the armed forces, clergy, and the general public. One West Point graduate wrote the President in 1926 to discern “where the U.S. government draws the chestnuts off the fire” in the hope that that the authorities would “see fit to abolish this un-American rule.”4 The Naval Academy’s chaplain, Sydney K. Evans reassured the concerned citizen that mandatory chapel attendance inculcates good character traits, solicits no parental resistance, and elicits thanks from those who underwent it. Many officers and enlisted men later expressed thanks for being “compelled to go to church” at the outset of their military careers. Evans noted that, absent the attendance requirement, “otherwise they would not have gone, and would never have learned to know and follow the standards and ideals of the world’s greatest Leader, as they know and follow him now.” Evans further justified the policy on the grounds of holistic character development and leadership preparation. “It would be presumptuous on [the naval officer’s] part to attempt, as a leader and teacher, to mold the characters of others unless his own character bears very definitely the marks of Honor, Truth, Duty, Discipline, and self-sacrificing Service . . . high qualities brought to his notice with emphasis systematically as he hears in the chapel, not the special teaching of any one religious body, but aspects of the life, teachings, and example of the Pattern Man.”5

‘We Should Hold the Line’

In a July 1943 responsorial letter to the U.S. Military Ordinate bishop’s unfounded concern that the Academy forced Catholic midshipmen officers to attend Protestant services, Superintendent John R. Beardall argued that the purpose of mandatory chapel “is to present to the Regiment of Midshipmen a form of worship in God as an essential factor in the development of a military character” and to ensure that their training “reflects the democratic form of government and life that our country stands for.”6 In 1946, as the Supreme Court argued in Everson v. Board of Education that the First Amendment’s “establishment of religion” clause prohibited the federal government from setting up a church, influencing citizens to profess belief or disbelief, or punishing individuals for attendance or nonattendance, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) first questioned the role of mandatory religious instruction, and violation of the midshipmen’s freedom not to worship at the Naval Academy.7

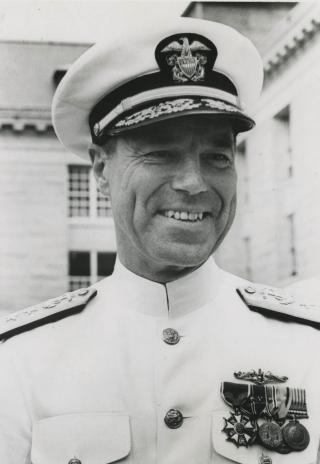

The Commandant of Midshipmen, Stuart Howe Ingersoll, a naval aviator and former light aircraft carrier combat commander during several 1944–45 actions in the Pacific war, provided his input for the Superintendent. “In my own heart I feel that we should hold the line. Attendance at some form of divine worship is indisputably an important factor in training, in molding of character, and in the development of the many attributes which we want our future officers to possess.”8 The Academy’s chaplain, Everett P. Wuebbens, defended mandatory attendance on the basis that the policies “have been tested in the crucible of American naval history” and “produced officers . . . whose courage and integrity of character have provided not only victory in war but also intelligent firmness in protecting the right to worship for dissenting minorities” among the populations of occupied territories placed under naval authority.9

The Superintendent himself, Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, another naval aviator and World War II combat commander, argued that mandatory attendance did not violate the midshipmen’s constitutionally protected religious freedom, stating, “the Navy demands honor, loyalty, integrity, and devotion to duty on the part of its officers. In the molding of the character required of its future leaders, it is considered that attendance at Divine Worship is essential.”10

(Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library, USNA)

Emerging Voices of Dissent

The Supreme Court again elicited citizen dissent against the Academy’s chapel requirement in 1948 when it argued in Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education that faith lessons given by religious leaders in public schools violated the Constitution’s establishment clause.11 “No doubt many of your men have the mental capacity to do a little thinking,” one frustrated Minneapolis denizen wrote the school’s flag secretary in the case’s aftermath, “and to such persons compulsory attendance at cave-man seances must be galling in the extreme.” Chiding the Academy authorities for “mixing with superstitious frauds and ecclesiastical rackets,” the man threatened to sue the school in court, concluding that “you have no right to compel your inmates to attend any church at any time.”12

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1952 decision in Zorach v. Clauson prohibiting the federal government from coercing citizens into church attendance, observing religious holidays or taking religious instruction, a local Annapolis Unitarian minister publicly argued against the compulsion of “inner religious commitment,” stating, “should there not be limits, even to the military, of the rights of authority over the souls of men? And if any part of the person is to be left sacred, should it not be the privacy and freedom of his religious beliefs?”13 The Superintendent, William R. Smedberg III, a World War II destroyer commander, defended mandatory attendance on the basis that religious instruction comprised part of “the whole education of a midshipman as a future naval officer” and that “providing religious services for the men under his command,” often in the absence of a chaplain within small ships or units, “is one of the duties of each commanding officer in the Navy.”14

To this reasoning, the command chaplain, Fred D. Bennett, annexed the objective to “train these young men in leadership, to become well-rounded men of high ethics and integrity,” which necessitated ancillary knowledge of religion.15 In response to one woman’s spirited and politically charged encouragement to ignore the Unitarian minister’s “red” strategy, Smedberg’s successor, World War II and Korean War veteran Charles L. Melson penned, “we shall stand firm in the established religious program that has been proved of worth for the past one hundred years.”16

Rulings by the Chief Justice Earl Warren Supreme Court in the early 1960s further confirmed the judiciary’s support for separation between church and state, particularly in public schools. By the early 1970s, national unrest over the Vietnam War and the end of the draft and transition toward an all-volunteer force complemented the gradual liberalization of the Naval Academy curriculum after the implementation of an academic majors program in 1968.

At the instigation of the Secretary of Defense’s office, in 1964 the service academies uniformly considered the tacit excusal of cadets and midshipmen bearing “strong personal convictions against going to religious services.”17 While evincing pride in the Naval Academy’s mission, the Chief of Naval Personnel further confirmed the school’s gray-zone approach to religious service excusals in 1966, stating, “although not specifically provided for in the section of the regulations” relating to divine services, “a sincere request to be excused by any midshipman who holds convictions which would preclude his attendance . . . would be seriously considered.”18

At their annual conference held in April 1969, the Superintendents of West Point, Annapolis, and the Coast Guard and Air Force academies argued that mandatory attendance instilled a necessary respect for religion and equipped officers to deal with future moral, spiritual, and ethical problems while concluding that “intelligent provisions must be made for bona fide cases where attendance would be in conflict with sincerely held convictions of individual cadets or midshipmen.”19 Later that year, the school’s staff judge advocate stated that, while the Academy authorities permitted conscientious exceptions to mandatory attendance, the excused “will be expected to spend the time in his room reading on the subjects of morals and ethics.”20

Grumblings Among the Brigade

While a Sunday morning morals and ethics class, held in Maury Hall and initiated by History Department instructor, Chosin Reservoir and Vietnam veteran Major Constantine Albans drew a limited number of theologically dissenting midshipmen to secular-oriented discourses on religion and philosophy throughout the 1968–69 academic year, between November and December 1969 a muster-board error implicated nearly two dozen midshipmen of the approximately 4,100-strong brigade in disciplinary actions for not attending religious services.21 Throughout the tense two months, several midshipmen petitioned the academy authorities for excusal from divine services. “I almost totally accept Fredrich Nietzsche’s condemnation of the Christian church,” wrote one midshipman, who added, “in my opinion a man forsakes himself if he acts according to the dictates of a deity that cannot be understood rather than according to the dictates of his own personal system of ethics.”22

Other midshipmen criticized the perceived hollowness of justifying compulsory attendance through invoking the Academy mission’s moral dimension. “I am no longer willing to compromise my personal honor in order to perpetuate the propaganda that implies that all midshipmen are devout or even religious,” wrote another midshipman. “I am unwilling to be associated with such blatant mistruth.”23 Organized religions are “intellectual authoritarianisms which repudiate honesty and discussion in order to suppress critical analysis of their tenets,” another midshipman added, concluding, “I should like to respectfully suggest that one may be honorable, ethical, and moral without being religious.”24

(Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library, USNA)

On 20 January 1970, six midshipmen joined a West Point Cadet, represented by ACLU lawyers, in a suit against Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird to end compulsory chapel attendance at the service academies. In his first statement to the court, Naval Academy Superintendent James Calvert, a submariner and World War II combat veteran, couched the requirement in terms that stressed the secular objective of midshipman moral development: “Because a genuine sense of honor, devotion to duty, and absolute integrity are qualities demanded of an officer, and because these qualities are fostered in religious principles and traditions, the Naval Academy requires midshipmen to attend chapel services.”25 In the Federal District Court in Washington, D.C., the plaintiffs, eventually comprising two West Point cadets and nine midshipmen represented by Catholic priest and Congressman Robert F. Drinan, argued that compulsory attendance violated the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment and constituted a “religious test” in violation of Article VI of the constitution. The plaintiffs desired a declaratory judgment that compulsory chapel attendance violated the constitutional provisions, and a permanent injunction prohibiting the academies from enforcing the regulations and disciplining the cadets and midshipmen involved in the court case.

Reaction to the case at the Academy remained mixed. On 8 February 1970, one day before the District Court Judge opened the trial for the docketed chapel attendance case, renowned evangelist Billy Graham preached a sermon at the Academy chapel’s Protestant service during a previously scheduled visit. Graham spoke of the relevance of the Bible to modern issues, and throughout his sermon exposited the existential problems confronting Americans via the statements and arguments of Friedrich Nietzsche, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Ernest Hemingway, Albert Camus, Eric Hoffer, and even actor Marlon Brando. After the service, Graham held an impromptu presser with local reporters in the Academy chapel’s vestry, wherein he answered questions about mandatory attendance. “I think it is a tremendous thing,” Graham declared. “It is part of the discipline, a part of the training, far beyond its being a religious service. We need it now more than ever before—it imparts a moral and spiritual strength.”26

Appeal to a Higher Court

According to a cease-and-desist letter from the attorneys representing the midshipman plaintiffs, when classes resumed after summer break in October 1970, the Commandant of Midshipmen convened an assembly of all the midshipmen at which he denounced the plaintiffs as being disloyal by summarily stating, “A loyal officer does not sue the Secretary of Defense or the Secretary of the Navy. The plaintiffs in the chapel case have done this, and these five individuals are sitting amongst you right now!”27

The following month, one of the original midshipman plaintiffs requested his name be withdrawn from the case, arguing the adverse publicity and the Academy’s firm legal response evinced a gradual and definite change in the brigade of midshipmen’s attitude toward the suit. “The Brigade now sees the suit as an insult to the Navy in general and to them personally,” the midshipman wrote, adding, “My loyalty to the brigade, the Navy, and my company must take precedence over my personal feelings.”28

In a 31 July 1970 ruling, the presiding judge granted an injunction forbidding the academies from disciplining the cadets involved in the case but found that mandatory chapel attendance violated neither the First Amendment to nor Article VI of the Constitution. The judge stressed the voluntary capacity of the cadets and midshipmen at the institutions, the forthrightness of the regulations and published catalogues respecting mandatory chapel, and the existing policy to excuse conscientiously objecting students. In addition to observing the traditional judicial deference granted the “the requirements of the military and its needs for discipline and training with the constitutionally protected rights and privileges of civilian society,” the judge described the Academy’s tradition of “an unbroken pattern of 150 years of mandatory chapel under the eyes of the President and the Congress, the military authorities, and the public in general.”29

ACLU lawyers filed an appeal in the District of Columbia circuit on 7 August 1970, and on 30 June 1972, the higher court overturned the district’s decision, arguing that worship and attendance at chapel services remained “indistinguishable.” The court further argued that chapel attendance, as a restraint on the free exercise of religion, violated the Free Exercise Clause, principally because the government “made no showing that chapel attendance requirements are the best or the only means to impart to officers some familiarity with religion and its effect on our soldiers.”30

The Department of Defense submitted the case to the Supreme Court on 27 October 1972, stating, “The danger our country faces today is the decline in spirit and morality, observable among young and old alike.”31 On 18 December 1972, the Supreme Court refused to review the case.

‘According to the Dictates of Your Conscience’

Midshipmen, academy authorities, and the public demonstrated differing reactions to the ruling. In a letter to the civilian service secretaries and Academy superintendents, the victorious West Point graduate that spearheaded the suit advertised the new possibility for genuine religious revival at the schools, stating, “Your religion by regulation was a theological albatross and its weight will be around your necks for some time.”32 In an essay in the Academy’s student-published Trident magazine, one midshipman wrote in the ruling’s aftermath, “Every Sunday morning, the brigade was insulted as a unit through forced participation in the ritual of marching off to chapel in a ceremony that often appeared to be nothing more than a spectacle.”33

During the case, one midshipman complained to the Academy Log periodical, “I fail to see how an unwilling, tired, and uninterested midshipman is improving his morals by sitting benumbed in chapel every Sunday. . . . You seem to have equated chapel attendance with morality, which is a rather unsophisticated notion.”34 Another midshipman questioned the moral tenor of the time and the impact of the current culture on future difficulties: “Our generation has long advocated breaking away from the establishment . . . those of us who are so occupied with finding themselves may realize . . . that in their middle and elderly years they will have to accept the responsibility for the society which they have created and all of the problems which it faces.” Reflecting on the tiresome routine of marching to chapel each week and the prospective human problems likely to face them as young officers, the editor concluded, “What we find unenlightening and uncool now may someday prove to be quite valuable.”35

(Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library, USNA)

“I am doubly troubled about the issue after hearing accounts from returning POWs that their faith in God and country was an essential factor in their survival,” wrote one mother to the Naval Academy commandant. “Perhaps many cadets in training today do not see the need for the type of courage, confidence, and faith that goes with religious training, but is it not possible at some future time these men might have need for these?”36

In a literary exchange with the Virginia Military Institute chaplain at the suit’s initial filing in spring 1970, senior Academy chaplain Robert F. McComas, former officiant on board the USS Minneapolis (CA-36) during World War II, wrote of the school clergy’s responsibility to support the Superintendent, stating that “our main business—more important than excellence in academics, top physical fitness, the best military training and discipline—is the spiritual undergirding that alone produces sound character, absolute honesty, unswerving loyalty, and devotion to duty unto death.”37

Superintendent William P. Mack, a surface warfare officer who escaped the 8 December 1941 Japanese bombing of Manila and went on to serve in World War II combat actions in the East Indies and Aleutians, disseminated an official memorandum describing the results of the Supreme Court’s decision to the brigade of midshipmen, just returning from the Christmas break during the first week of January 1973.

“Although attendance at religious services is now optional,” Mack stated, “I urge each of you to worship according to the dictates of your conscience. As officers in the naval service, your personal beliefs will often be tested, and in times of stress your men will look to you for spiritual as well as professional guidance. I believe that you owe it to yourself and to your men to gain an insight into the moral, ethical, and religious dimensions of leadership.”38

1. William F. Fullam, Letter to Parents (or Guardians) of Midshipmen, 1 February 1915, Special Collections & Archives Department [hereafter: SC&A], Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy, Record Group 405 [hereafter: RG 405], vol. 553, entry 57.

2. United States Department of the Navy. Regulations of the U.S. Naval Academy: Parts I and II (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1916), 161.

3. United States Department of the Navy. Regulations of the United States Naval Academy (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1929), 118.

4. A. Major to the service academies, via the President of the U.S., 26 August 1926, folder 12, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

5. Sydney K. Evans to A. Major, 14 September 1926, folder 12, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

6. John R. Beardall to John Francis O’Hara, 8 July 1943, folder 13, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

7. Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S., 15–16; Nannette Dembitz, Staff Counsel, ACLU to VADM Aubrey W. Fitch, 7 November 1946, box 2, folder 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

8. Stuart H. Ingersoll to Aubrey W. Fitch, 17 December 1946, folder 13, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

9. Edward P. Wuebbens to Aubrey W. Fitch, 26 November 1946, folder 13, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

10. Aubrey W. Fitch to Nanette Dembitz, Staff Counsel, ACLU, 23 December 1946, folder 13, box 1, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

11. Illinois ex rel. McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 U.S., 212.

12. Frank C. Hughes to R.G. Leedy, USN Flag Secretary, 31 March 1951, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

13. Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S., 314; Curtis Crawford to Charles L. Melson, 8 September 1958, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

14. William R. Smedberg III to Nancy M. Sherman, 10 April 1956; William R. Smedberg III to Curtis Crawford, 19 September 1957, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

15. Fred D. Bennett to John V. Phelan, 15 September 1958, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

16. Mrs. Alexander F. Jenkins to Charles L. Melson, 1 September 1958, and Charles L. Melson to Mrs. Alexander F. Jenkins, 16 September 1958, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

17. Norman S. Paul, Assistant Secretary of Defense to Secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, 19 March 1964, folder 2: Religious Services, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

18. B. J. Semmes Jr., Chief of Naval Personnel, to Mr. S. Leon Levy, 12 September 1966, folder 2: Religious Services, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

19. James Calvert et al., “Eleventh Annual Congress of Superintendents of U.S. Military Academies,” appendix F: Chapel Attendance, 18 April 1969.

20. C. E. Waite, JAGC, Staff Judge Advocate, Question and Answer Section, Shipmate, December 1969.

21. B. B. Brown, Head Executive Department to Commandant of Midshipmen, Memorandum: Battalion Audits of Chapel/Church Parties, 10 January 1970, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

22. Midshipman Letter to the Commandant, 14 January 1970, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

23. Midshipman Letter to the Superintendent, 1 December 1969, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

24. Midshipman Letter to the Commandant, 26 February 1970, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

25. James Calvert, “Affidavit,” 4 February 1970, 2–3, Anderson v. Laird, 70 Civ. A. No. 169–70, vol. 1.

26. “Billy Graham Preaches at Naval Academy” Annapolis Evening Capitol, 9 February 1970.

27. Warren K. Kaplan to Joseph M. Hannon, U.S. Attorney, 7 October 1970, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

28. Midshipman letter to Lawrence Speiser, 5 November 1970, folder 2, box 10, entry 151b, RG 405.

29. “Howard Corcoran, “Opinion,” 31 July 1970 Anderson v. Laird, 70 Civ. A. No. 169–70, vol. 1.

30. David Bazelon, “Opinion,” Anderson v. Laird, 151 U.S. App. D.C. 112; 466 F.2d 283, 45.

31. John Malley, Amicus Curiae Brief to the SCOTUS, 27 October 1972, folder 5900/1, 1972, in Superintendents Serial Files, 1960–1981.

32. Michael D. Anderson to the Secretaries of Defense, Army, Navy, Air Force, and Superintendents, USMA, USNA, and USAFA, 11 January 1973, folder 1730, Religion, box 38, entry 151a, RG 405.

33. Bruce A. Castleman, Opinion, “There is a Problem Here . . .” Trident, February 1973, SC&A, Nimitz Library.

34. Stephen A. Wohler, letter to the editor, Log of the U.S. Naval Academy 59, no. 9 (10 April 1970): 6.

35. D.A.E., “Editorial,” Log of the U.S. Naval Academy 59, no. 4 (30 January 1970), 1–2.

36. Mrs. Joy Wood to Max K. Morris, 30 April 1970, folder 1730, Religion, box 38, entry 151a, RG 405.

37. Robert F. McComas to Robert K. Wilson, 9 February 1970, Correspondence/Chronological File January–April 1970, box 2, entry 151i, RG 405.

38. William P. Mack, Memorandum for the Brigade of Midshipmen, Faculty and Staff, “Attendance at Sunday Morning Activities,” 5 January 1973, Reference File: Midshipmen – Mandatory Chapel Attendance, RG 405.