First of Two Parts

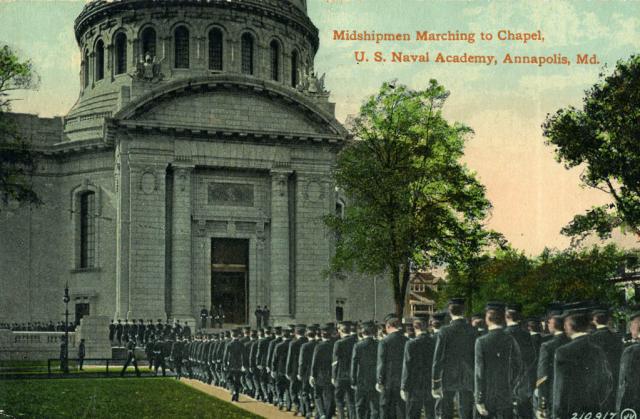

In December 1972, the Supreme Court, by refusing to take up an appeal ended a 127-year U.S. Naval Academy policy of mandatory midshipman attendance at religious services. On 29 December, the Reverend James F. Madison of St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Annapolis wrote a letter of welcome to the brigade of midshipmen just returning from Christmas break. “God rest you merry, Gentlemen, Let nothing you dismay,” Madison musically wrote, “in freedom come to church again, to worship God Sunday, And do it not because you must, But just because you care . . . O Tidings of freedom and joy, Freedom and joy.”

Encouraging midshipmen congregants to bring friends and attend Sunday services voluntarily through self-discipline, Madison wrote, “It has been good to have you who have come to join with us under the order of compulsory chapel . . . it will be better for us all now that you can attend simply because you want to come.” Perusing Madison’s letter on his desk on the Naval Academy grounds a week later, the commandant of midshipmen, Max K. Morris—a 1947 graduate—scribbled in the margin, “you always could—even in my day—invite friends, Attendance dropped from 176 men to 16. Happy New Year!”1

‘Take Care that Divine Service Be Performed’

Naval religious requirements went back to the earliest days of the fleet: On 28 November 1775, when the Continental Congress approved a set of rules for the nascent Continental Navy, Article 2 stated, “The commanders of the ships of the Thirteen United Colonies are to take care that divine service be performed twice a day on board, and a sermon preached on Sundays, unless bad weather or other extraordinary accidents prevent it.” The following article enshrined the inviolability of religious decorum. “If any shall be heard to swear, curse or blaspheme the name of God, the captain is strictly enjoined to punish them for every offense, by causing them to wear a wooden collar or some other shameful badge of distinction, for so long a time as he shall judge proper.”2

After the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, the “Act for the government of the Navy of the United States” of 2 March 1799 stipulated that “Commanders of the ships of the United States, having on board chaplains,” provide divine services twice a day and, weather permitting, a sermon on Sundays.3 The Act for the better government of the Navy passed the following year added the qualifier that commanders of ships with chaplains ensure that divine services were performed “in a solemn, orderly, and reverent manner,” and that “they cause all, or as many of the ship’s company as can be spared from duty, to attend at every performance of the worship of Almighty God.”4

In 1845, near the conclusion of his first year as Superintendent of the new U.S. Naval School, Captain Franklin Buchanan appended the earlier regulations to the first Plan and Regulations of the Naval School at Annapolis, which Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft approved on August 28, 1846.5 In addition to changing the title of the institution to the U.S. Naval Academy, the Board of Officers and Professors that convened in October 1849 to revise the regulations stipulated that divine services performed on Sunday “shall be attended by every person attached to the academy.”

The new regulations mandated the midshipmen’s assemblage in the chapel for prayers 15 minutes before breakfast and warned that any of the students “who shall behave indecently or irreverently while attending divine service, or shall use any profane oath or execration, or profane the Sabbath, shall be dismissed from the service, or otherwise less severely punished.”6 (The 1855 regulations would add the qualifier that “a compliance with the forms and ceremonies of divine service is earnestly recommended for the observance of all persons who attend.”)7

Academy authorities enforced that compliance, even while later regulations permitted conscientious objection. Commenting on the “irregularity and indecorum” occasionally characterizing the midshipmen’s conduct at divine services, the Academy’s second superintendent, Commander George P. Upshur, described violation of “the conventional rules of Christian society by an officer under my command” as “ungenteel, unofficerlike, irreverent, and I presume, though I do not know the fact . . . also unlawful in the state of Maryland.” Singling out acting midshipman Hunter Davidson’s misconduct in chapel, Upshur remarked, “I am very sure that the wanton disturbance of any congregation while engaged in the worship of God, ought to be made an indictable offense by the laws of every Christian land.”8

‘Devils as Far as Religion Is Concerned’

Ten years later, acting midshipman Alfred Thayer Mahan routinely lampooned the Academy’s first Episcopalian chaplain, George Jones, whom the future globally renowned naval strategist and historian christened “Slicky” in letters overflowing with sardonic wit. “We have listened to a delightful sermon from Old Slick on rum drinking,” Mahan wrote to a friend in December 1858. “It is really the most disagreeable thing in the world to sit quietly and listen to the rant and cant of that intolerable old poker.” Detesting the tracts delivered at the mandatory Sunday morning service, and doubting their moral influence at the school, Mahan wrote of his midshipmen colleagues, “as bad as the fellows are usually, they are devils so far as religion is concerned when just out of Old Slicky’s hands.”9

Less than a month later, Mahan received his means to escape George Jones’ temperance lectures. On 17 January 1859, the Navy Department modified Academy regulations to permit officers’ excusal from mandatory Sunday morning chapel attendance if they provided their declaration “in writing that they cannot conscientiously attend.” Parent- or guardian-written declarations similarly exempted midshipmen from mandatory attendance at the school chapel and permitted them to either form church parties to join Annapolis congregations or abstain from all services.

The Department’s modification authorized the Academy superintendent to prescribe regulations “as will insure from those excused a decent observance of the Sabbath, during the performance of divine services.”10 Within four weeks of notifying the midshipmen of the regulation change, at least three parental letters requesting conscientious withdrawal from Academy chapel services arrived.

One fourth-class midshipman’s father requested his son’s permission to attend Presbyterian Church services. Academy Superintendent George S. Blake replied by requesting the father write him a separate Sunday morning exemption request “upon the grounds of conscientious scruples,” and assured him of his son’s continuous permission to attend Presbyterian services on Sunday afternoons and communion mornings. “Though our services at the Academy happen now to be of the Episcopalian form,” Blake wrote the Ohioan father that “they may be Presbyterian very soon, as we have chaplains of different denominations in the Navy, and no particular form of worship is prescribed for any of our Naval or military establishments.”11

A House Divided—and a Divine Oath

Throughout the Civil War, Academy and Navy Department authorities and visiting speakers increasingly utilized religious faith to fortify personal integrity and to remind the midshipmen of the divine foundation of their oath to support the Constitution. During the tense weeks between Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration and the attack on Fort Sumter, the Academy’s religious ministry appealed to the students’ integrity and character development to reject disloyalty. In the school chaplain’s absence in March 1861, Professor Joseph Everett Nourse, professor of ethics and English studies, himself, a Presbyterian minister, came aboard the frigate Constitution, then berthed at the Academy as a barracks and school ship, to officiate services for the fourth-class midshipmen. He focused on Psalm 50:23, “Whoever offers praise glorifies Me; and to whom who orders his conduct aright I will show the salvation of God.”

Reflecting on these services and the tense period a year later, Professor Nourse wrote, “I strove to conduct the service with a distinct bearing on obedience to authority and on personal peace. For while I excused no one for disloyal sympathy, I could not forget that those youths were of but partially formed characters and would be less likely to maintain their integrity if drawn into heated discussions.”12

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles enclosed a special letter in the permits granting prospective midshipman candidates a seat at the spring 1863 entrance examination for the Academy (relocated to Newport, Rhode Island, for the duration of the Civil War). Extolling loyalty to the government and the Constitution, Welles reminded the candidates of their duty to remain true to the flag. Fidelity to their oaths, Welles extolled, is inviolate, for “no human power can absolve them from that obligation. The madness of the hour may cause a misguided man to forget that he has called his God so to deal with him as he shall keep or break his oath, but the time will come, even in this world, when the sin of perjury will lie heavy on his soul.”13

Visiting officiants and speakers further reinforced the divine foundation of the oath. Five months before delivering a herculean two-hour dedication ceremony preceding President Abraham Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg, Edward Everett—a Unitarian minister and former Secretary of State, Massachusetts governor, statesman, and Harvard University president—delivered the commencement speech for the 21 midshipmen of the Class of 1864, assembled in Newport’s Second Baptist Church. The oath—loyalty’s most physical and enduring manifestation—was a “sheetrock of allegiance,” Everett declared, rested on the moral foundation binding “the soul of the creature to the footstool of the Creator.”

While law may fail to deter the ambitious and hot-tempered man, and honor prove meaningless before the mercenary and coward, “the oath of God,” upon the naval officer’s soul, “was clothed with a mysterious power, which awed the faithless into obedience, and nerved the arm of the craven with courage.”14

Although omitted by the school’s two sets of regulations published between 1876 and 1894, the Academy tacitly continued the 1859-mandated policy, replicated in the 1895 regulations, that excused midshipmen from attendance at Sunday morning religious services until 1916.15 Despite excusing conscientious objectors and permitting denominationally dissenting communicants to attend other Christian churches in Annapolis, Academy authorities continued to enforce compliance with the forms and ceremonies of the school’s Sunday morning Episcopal service throughout the period. The spirit of the Academy’s regulations enforcing compliance with outward religious decorum are best summarized by young Lieutenant Commander Stephen B. Luce’s 1863 order for the midshipmen embarked on the school’s annual summer practice cruise. “Those who are so unfortunate as to belong to no church whatever,” Luce ordered, “should remember that it is but the part of a well-bred gentleman to show respect for religion, and when attending service, evince at least an outward regard for the sacred exercise.”16

On other occasions, the school’s authorities enforced decorum with exacting discipline. On 10 January 1870, Academy Superintendent John L. Worden, former commander of the USS Monitor in her March 1862 engagement with the CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads, sentenced a pair of midshipmen to two days’ solitary confinement on bread and water for “persistent and willful disorderly conduct, during services in the Chapel.”17 Four days later, Worden issued a reconstructive-oriented order suspending normal study routine on Sundays to provide the midshipmen “opportunities for religious instruction and meditation” and encouraging attendance at the chapel’s voluntary nightly service at 1930 hours. Worden directed midshipmen not availing their privileges of attending chapel or church in Annapolis on Sunday afternoons and Tuesday evenings to confine themselves to their rooms to ensure “due regard to a proper observance of the Sabbath.”18

In February 1874, Worden restricted four cadet-midshipmen to the academic limits for one month and deprived their recreation for ten days for playing cards and “Desecration of the Sabbath.”19 Other records evidence the chaplain’s influence in correcting moral deficiencies of midshipmen remanded to his care. After the 1874 summer cruise commander notified the superintendent that a second-class midshipman cursed a warrant officer in “language better suited to a denizen of Billingsgate than to a young man claiming to be a gentleman,” Worden recommended his commandment “to the attention of the Chaplain, with the view of his moral reform and to his cultivation of gentlemanly habits.”20

Increasing Denominational Diversity

Even as the authorities enforced religious decorum, the Academy’s religious diversity exponentially increased. In a letter to the Secretary of the Navy submitted to Congress in February 1872, Worden wrote of the conduct of the first two Japanese citizens admitted to the Academy. Although they were adherents of Shintoism, Worden remarked on the Japanese midshipmen’s total compliance with Academy rules and routines, “even to attending morning prayers and divine service on the Sabbath. In the latter regard their seeming interest and respectful deportment is not at all behind that of their nominally Christian fellow-students.”21

Out of the 383 congregants at the first academic year service on 1 October 1882, 49 percent registered as Protestant Episcopal. Close to 10 percent of all registrants identified as Presbyterian. Of the 179 naval cadet congregants, 20 registered as Methodists. Other cadet registrants included 13 Baptists, five Unitarians, three Lutherans, and three Jews. Two cadets registered each as “Free Thinkers” and Reformed. Denominations registered by only one cadet included Congregationalist, Swedish origin, Quaker, Dutch Reformed, “Protestant,” Campbellite, and “Liberal.”22

Reminiscing about his Class of 1902 colleague Horace Scudder Klyce of Arkansas, the Academy Museum’s curator, Rear Admiral Harry Baldridge, recalled the Bear State atheist’s successful attempt to secure conscientious excusal from Sunday morning chapel attendance. “To the best of my recollection,” Baldridge mused, “he did have to do two things on Sunday forenoons, namely, be in full dress at inspection of rooms before formation to march to chapel, and, attend that formation and then to remain in his room until chapel services were over.”23 The 1902 Lucky Bag yearbook esoterically described Klyce as “an ardent supporter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, but frequently absent church formation.”24

During World War I, Academy authorities ended conscientious excusals from all Sunday morning divine services, a policy change effectively prohibiting midshipmen from simply remaining in their dormitories. This elicited a persistent tradition of resistance—ultimately culminating in the end of mandatory chapel attendance more than half a century later.

Continued Next Week

1. James F. Madison to Midshipmen of the Brigade [with notes from commandant, Rear Admiral Max K. Morris] Special Collections & Archives [hereafter SC&A], Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy, 29 December 1972, folder 1730, Religion, box 38, entry 151a, Record Group 405 [hereafter RG 405].

2. Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies of North America (Philadelphia: William and Thomas Bradford, 1775) [printed by the Naval Historical Foundation, 1944].

3. An Act for the Government of the Navy of the United States, March 2, 1799. United States Statutes at Large, vol. 1, ed. Richard Peters (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1845), 709–10.

4. An Act for the Better Government of the Navy of the United States, 23 April 1800, United States Statutes at Large, vol. 2, ed. Richard Peters, (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1845), 45.

5. Plan and Regulations of the Naval School at Annapolis (Washington, DC: C. Alexander, Printer, 1846), Digital Collection, Special Collections and Archives Department, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy.

6. Board to Revise the U.S. Naval School Rules and Regulations, chaired by Commodore Shubrick, Regulations for the U.S. Naval School, October 1849, Article 24.

7. U.S. Department of the Navy, Regulations of the United States Naval Academy, 1855 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1855), ch. 19, p. 42.

8. George P. Upshur to Cornelius McLean, 22 March 1849, vol. 1, Entry 1, RG 405.

9. Alfred T. Mahan to Samuel A. Ashe, 12 December and 29 October 1858, in Letters of Alfred Thayer Mahan to Samuel A’Court Ashe, 1858–1859, ed. Rosa Pendleton (Durham, NC: Duke University Library Bulletin, 1931), 48, 11.

10. Isaac Toucey, Secretary of the Navy, Letter, “to Naval Academy Superintendent George S. Blake pertaining to modification of religious observance regulations,” 17 January 1859, vol. 9, Box 1, Entry 4, RG 405.

11. George S. Blake, Letter, “to A. Hivling of Ohio, pertaining to his son’s attendance at Presbyterian Church services,” dated 26 February 1859, vol. 9, box 1, entry 4, RG 405.

12. “Record of Discourses delivered at the Naval Academy during the incumbency of Chaplain Junkin,” Chaplains’ Register, entry 151i, RG 405; Nourse to John P. Hale, Chairman of the Naval Committee, U.S. Senate, July 8, 1862, folder 8, box 8, entry 25, RG 405.

13. Gideon Welles, Letter, “to Naval Academy Candidates with Permit, Outlining Admittance Qualifications,” 31 January 1863, in Annual Register of the United States Naval Academy (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1866) 32–34.

14. Edward Everett, “An Address Delivered at the Annual Examination of the United States Naval Academy May 28, 1863” (Riverside, Cambridge: H. O. Houghton, 1863), 10–11, 15.

15. United States Department of the Navy, Regulations of the United States Naval Academy, 1876 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1876), 40–41; U.S. Department of the Navy, Regulations of the United States Naval Academy, 1887 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1887), 70; U.S. Department of the Navy, Regulations for the Interior Discipline and Government of the U.S. Naval Academy (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), 35.

16. Luce, “order at sea,” 14 August 1863, in Albert Gleaves, ed., Life and Letters of Rear Admiral Stephen B. Luce (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons), 85, 89.

17. John L. Worden, Order, “No. 7, punishing Midshipmen Fowler and Culp,” 10 January 1870, vol. 311, box 1, entry 48, RG 405.

18. John L. Worden, Order, “No. 8, proscribing a new Sunday afternoon routine,” 14 January 1870, vol. 311, box 1, entry 48, RG 405.

19. John L. Worden, Order, “No. 37, punishing Cadet Midshipmen Gleaves, Harkness, Orchard and Machida,” 17 February 1874, vol. 312, box 2, entry 48, RG 405.

20. John L. Worden, Order, “No. 119, punishing Cadet Midshipmen Castle, Sheeks, and Hannum,” 31 July 1874,” vol. 312, box 2, entry 48, RG 405.

21. John L. Worden to George M. Robeson, 19 January 1872; U.S. Senate, Letter from the Superintendent of the Naval Academy in Relation to the Japanese admitted into that Institution as Cadet Midshipmen, 42nd Congress, 2nd Session, 19 February 1872, Miscellaneous Document no. 77, serial vol. 1482.

22. Chaplain, U.S. Naval Academy, “Congregation,” vols. 2–3, series 1, entry 151i, RG 405.

23. Harry Baldridge, “Memorandum for Commander Burke,” 2 December 1946, folder 2, box 2, subseries 4a, entry 39b, RG 405.

24. U.S. Naval Academy, Lucky Bag, 1902, RG 405.