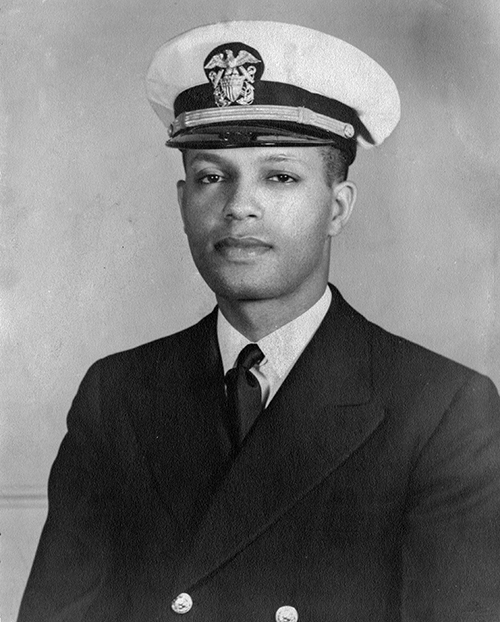

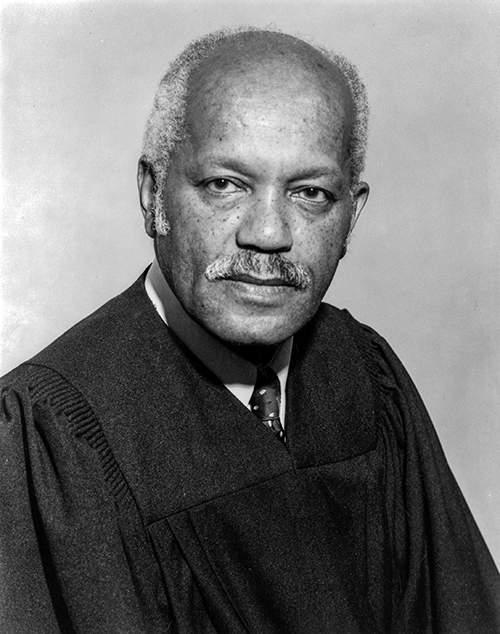

White, William Sylvester, The Hon. — Member of the Golden Thirteen

(1914–2004)

After growing up in Chicago, White got his education in the city, including a law degree from the University of Chicago. Following private practice, he became an assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois in 1939 and remained in that capacity until he enlisted in the Navy in 1943.

After recruit training at Great Lakes, he was part of a group of 16 men who underwent training as officers. In March 1944 White was one of a group of 13 men who became the first black U.S. naval officers on active duty. He served for the remainder of the war in Navy public information, first at Great Lakes, later in Washington. After the war he resumed his legal career in the U.S. Attorney's Office. He joined the cabinet of Illinois Governor Otto Kerner in 1961. In 1964 he became a judge, and from 1980 until his retirement in 1991 he was a justice of the Illinois Appellate Court.

The principal focus of the oral history is Justice White's recollection of his naval service, including an analytical view of the service of blacks in the Navy and their acceptance into U.S. society as a whole.

Interview

Justice White: Nobody's ever asked me about the evaluation of the Navy's implementation of Forrestal's policy of nondiscrimination, of affording greater opportunity for blacks and getting Lester Granger to go make that trip. Has anybody ever written anything about that?

Paul Stillwell: I'm not aware of it. It could have been.

Justice White: Let me just give you a thumbnail, and that's how I caught up with these guys. I stayed at Great Lakes most all my tour there. If I had known everything was so history-making, I would have stolen and kept copies of the news releases. But we sent out more news releases relating to Great Lakes and the U.S. naval hospital, almost rivaling the lines of type got by the Army. We had to cater to home town stuff. We did that even before home town news came out, and took advantage of returning Navy people at the hospital and whatnot. We had an excellent photographer and a couple of good writers, and we had a CBS radio broadcast that came on on Sunday night.

I forgot where I was going.

Paul Stillwell: You were talking about Lester Granger.

Justice White: Well, a couple of things happened. There was Port Chicago, and the Navy decided, "Never again will we have a shore installation that's 100% black. We're going to scatter these guys throughout the service, because this just looks bad." And it did look bad, and it was bad. So they got no more than such and such a percent of any shore installation that would be black. But you had blacks all over the globe.

So Forrestal said to Lester Granger, who was the head of the National Urban League, "I want you to go find out how Navy policy is being implemented at these far places." By that time I was in Washington, and they sent me along as a public information officer, to accompany Lester Granger on this tour. Now, of course, I had been in Washington, sleeping well and eating well. [Laughter] And we went in a fine plane that was ordinarily used by the Secretary of the Navy, and I visited these places. I met Dille in Hawaii.

Anyhow, I remember I picked up Arbor in Guam, Nelson in Eniwetok. We went all the way out to New Guinea. I don't think anybody got that far, at least not while I was there. Sublett, I think, was on Eniwetok.

Paul Stillwell: Yes, he was. Martin was also.

Justice White: I guess I should have felt a little bit of shame, you know, I was living so good when those poor devils weren't, but I didn't feel ashamed at all. In fact, it kind of tickled me a little bit.

Paul Stillwell: What was the substance of the trip? What were you doing?

Justice White: Well, the substance, I can sum it up. The purpose of the trip was to see whether the Navy, in its remote places, was taking advantage of the opportunity to utilize fully Negro personnel, or were they restricting them, or restricting their use of them, to the more traditional roles. Lester Granger's findings, as I remember, were the farther you get from Washington, the less impact the words of the Secretary of the Navy had. Once again, you see how public relations and personnel kind of get mixed up. That's a trip that Goodwin, with his personnel expertise, could well have taken, but they did it the other way around.

About this Volume

Based on two interviews conducted by Paul Stillwell in October 1986 and July 1988, the volume contains 130 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1990 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use.