Young men entering the Navy are introduced to their new world by way of The Bluejacket’s Manual. It is unlikely that its first author, Lieutenant Ridley McLean, had any inkling his book would become an American institution, but this practical guide has been in print for more than a century, serving U.S. sailors as both an introduction to the Navy and a handy reference guide in their continuing service.

In the first edition, McLean articulated these purposes in succinct terms, writing that “this manual is designed to be of value to men just entering the service . . . and for this reason an attempt has been made to give, in condensed form, . . . information with which every person in the naval service should be familiar.” He added, “petty officers will find this book valuable for reference.” One of his goals (as he articulated in a 1906 issue of the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings) was to provide information that would counter the negative effects on morale caused by “kickers,” a contemporary slang term applied to frequent complainers.

The first edition, printed in 1902, measured four by five-and-a-half inches and slightly more than three-quarters of an inch thick, with seven chapters covering seamanship, ordnance and gunnery, signals, boats, “Duties in Connection with Life on board Ship,” “Petty Officers and their Duties,” and “Miscellaneous Extracts from Navy Regulations.” The manual also included two special pockets built into the binding that sailors could use to stash additional notes or other items.

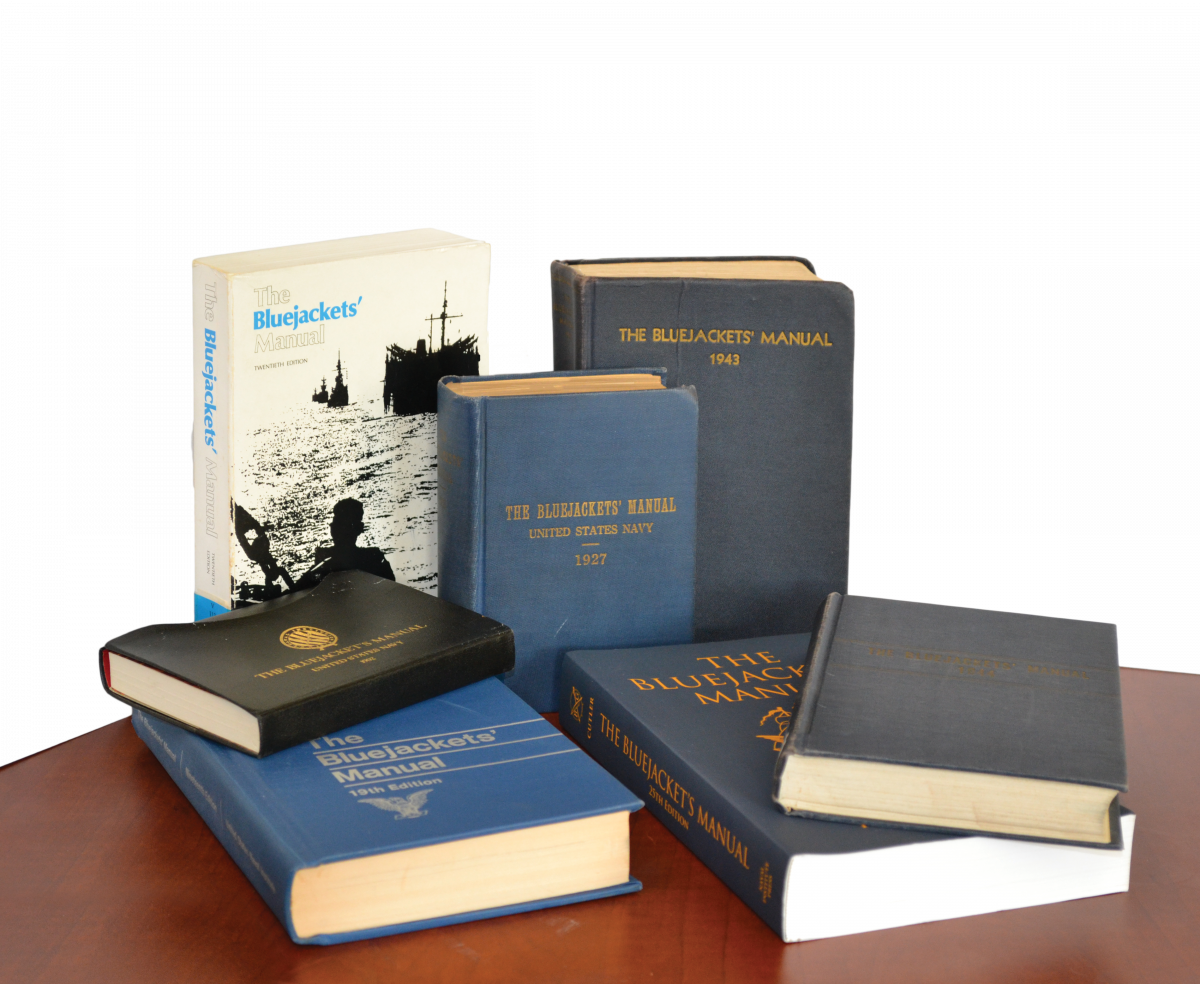

Since its first printing, The Bluejacket’s Manual has undergone various changes in shape and size as well as content. As both technology and American culture changed, new terms were added to that strange lexicon of the sea, and as more topics were added and the manual grew in size, it lost the pockets.

By the end of World War I, the sixth edition had grown to more than an inch-and-half thick and included sections for chief petty officers and specific information for various ratings such as blacksmiths, carpenter’s mates, watertenders (i.e., stokers or firemen), machinist’s mates, shipwrights, and pharmacist’s mates. Shortly thereafter, the book lost its index—an unfortunate choice that reduced its utility. Curiously, the book’s title also was changed—with the possessive apostrophe moved to follow the “s” (as in Bluejackets’).

In 1943, the 11th edition of The Bluejackets’ Manual ballooned to 1,150 pages—nearly two inches thick and weighing just under two pounds. This edition also reintroduced the index, which has remained in all subsequent editions. Coupled with the training provided at the Navy’s “boot camps,” the manual’s wartime mission was to help turn an ordinary civilian into “an able seaman and a thorough man-of-war’s man,” as Admiral William D. Leahy noted in the preface to the edition. This was no small task considering the nation was in the midst of a global war and ordinary citizens were being transformed into sailors by the hundreds of thousands.

It was packed with page after page of topics that included seamanship, gunnery, communications, navigation, landing force procedures, hydraulics, electricity, ship characteristics, first aid, personal hygiene, naval customs, and painting. Enlisted men were advised that “each man must know all there is to know about his own battle station as well as adjacent stations so that in the event of material casualty no time will be lost in dealing with the damage” and “in firing at living targets except at very short ranges, aim should be taken at the bottom of the target.” A section on “War Emergencies and Small Boat Navigation” explained that “naval personnel may find themselves in a boat on the high seas and facing the problem of reaching the nearest land,” and offered guidance for survival. The 11th edition also included a section on asbestos suits, explaining that “while asbestos will not burn, it will conduct heat” and advised how best utilize them in firefighting.

Among this harrowing guidance were more mundane topics such as the proper wearing of the uniform, how to salute, and how much pay to expect. One can only begin to imagine the reactions of young men fresh from the cornfields of Kansas or a corner drugstore in Omaha when they first read the manual during their basic training. Yet it is even harder to imagine making this transition without such a book.

The 12th edition was pared down to 600 pages in 1944, a change largely brought about by the evolving nature of the war. By that time, the Navy had become much more organized and efficient, and this is reflected in both the structure and content of the 1944 manual. Close coordination with a much larger Marine Corps led to the demise of sections dealing with combined landing parties consisting of both sailors and Marines—a large part of previous editions. The earlier editions also included discussions about learning to swim, but the new streamlined edition assumed sailors could swim and focused on water survival techniques. It also included a tabbed section on communications and signals for easy reference. While this edition retained instructions on rowing, it no longer included a 40-page chapter on sailing.

With the 22nd edition in 1998, the name of the book was returned to Bluejacket’s, and that remains the standard today. The 25th and most recent edition has undergone a complete reorganization that includes chapters for introductory material and includes tabs of easily accessible reference information on major topics.

Today there is a collector’s market for The Bluejacket’s Manual, and the earliest editions are rare and costly. Seventeen authors of the manual have been specifically identified over the decades; on some editions no authors are listed at all, and on other editions the author is listed simply as “Navy Department” or “Bureau of Navigation.” Collectors often are frustrated by anomalies in edition numbering. Several different revised and enlarged versions of the first edition were printed after 1902, and during World War I, publishers other than the U.S. Naval Institute were licensed to print the book—and they did not necessarily adhere to the sequence of edition numbering implemented by the Naval Institute starting in 1915 with the third edition. Consequently, there are different versions all claiming the same edition number, and many have no edition number at all. The Naval Institute has been the sole publisher from the eighth edition of 1938 onward, and those edition numbers have remained consistent.

Although the term “bluejacket” is used less often today than “sailor,” the original name has been retained out of respect for tradition—something the Navy has always valued highly. American bluejackets themselves have evolved, and differences in the “tone” of the 1902 edition and the current one are apparent. Today’s volunteers are more informed and often more educated than sailors of yesteryear, and the content of the current manual reflects these differences.

While The Bluejacket’s Manual has evolved through its 25 revisions (and counting), its original purpose has remained steadfastly on course. Like its predecessors, the latest edition makes no attempt to be a comprehensive textbook on all things naval—to do so today would require a multivolume set that would defy practicality—but it continues to serve modern sailors much as the original did, converting civilians to sailors and providing a handy reference as they continue their service, whether for one “hitch” or for an entire career.