Barnaby, Ralph S., Capt., USN (Ret.)

(1893–1986)

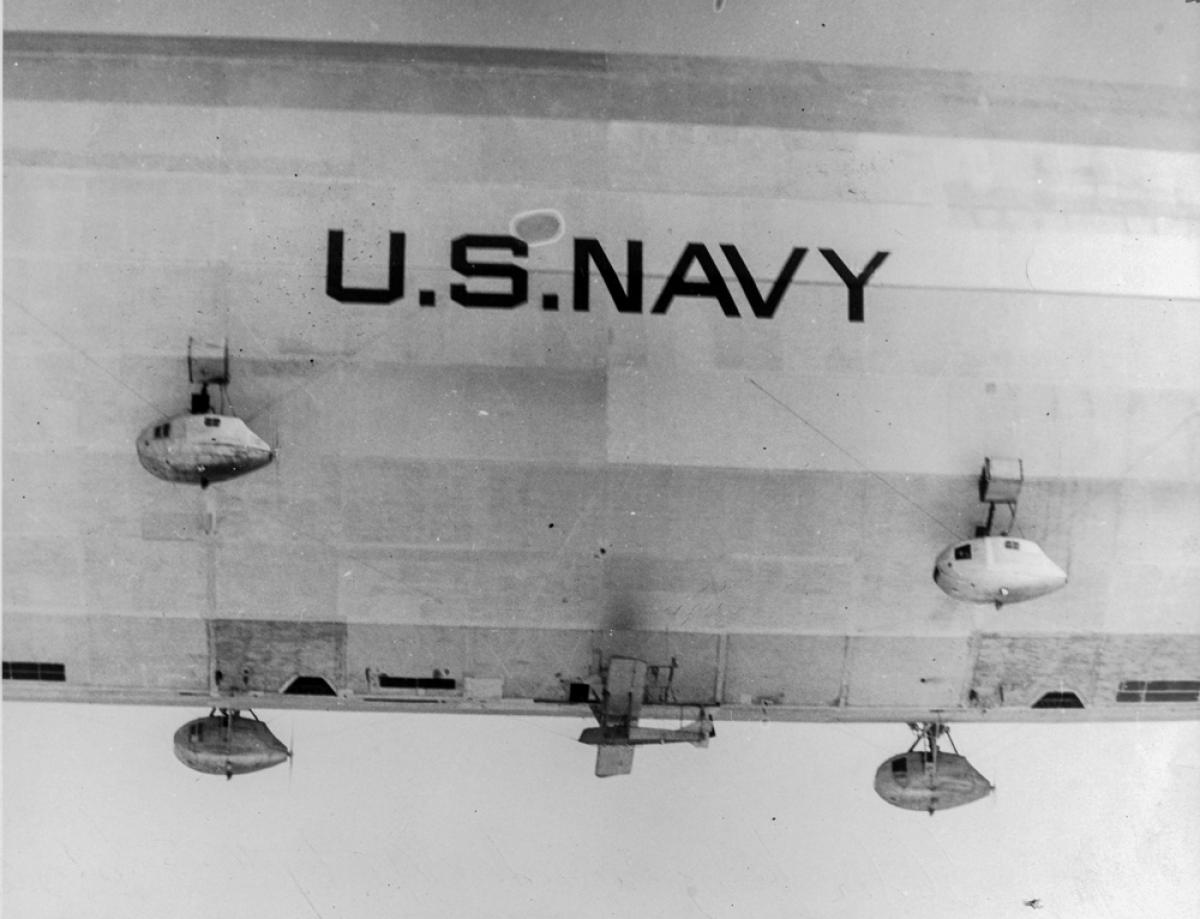

Barnaby was the first person in the United States to earn a soaring license. He began developing gliders not long after the pioneering work of Orville and Wilbur Wright. The memoir of his naval service focuses primarily on his glider experiences, including his achievement as the first person to descend by glider from an airship, the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3), in 1930 He later used gliders in naval aviation training at Pensacola, Florida. During World War II he was an engineer at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia and commanding officer of the Naval Air Modification Unit at Johnsville, Pennsylvania.

Excerpt

In this audio clip from his oral history, Captain Barnaby describes his celebrated, headline-making glider flight from the USS Los Angeles (ZR-3) on 31 January 1930 — and the effect of the icy conditions on the undertaking.

Captain Barnaby: I'll never forget that morning. I was up at 5:00 o'clock, because at 6:00 o'clock they were going to walk the airship out of the hangar. It was 16 above zero at that time. Clear, crisp, beautiful day, but cold — bitter cold. The first hitch was they couldn't get the hangar doors open. The ice had frozen in around them, so actually it was considerably later — a couple of hours later — before they brought the airship out.

Doctor Mason: Were there newspapermen about?

Captain Barnaby: Oh, yes, a lot of them. As a matter of fact, they had three blimps that accompanied us and flew along with us with newspaper reporters and movie cameras.

Doctor Mason: Were they Goodyear blimps?

Captain Barnaby: Two of them were blimps that Goodyear had built for the Navy. The third one was the old ZMC-2, designed by Ralph Upson of the Detroit Aircraft Corporation. It was a non-rigid but had a thin aluminum skin instead of the usual fabric skin. That ship was quite a historic experiment.

Doctor Mason: Was Admiral Moffett also present?

Captain Barnaby: No. Admiral Moffett at that time was attending the famous disarmament conference in London.[1] He was away, and Towers was assistant chief at the time and acting in his absence. After they'd finally walked the airship out and had it balanced and everything, then we attached the glider. For the takeoff, I didn't ride in the glider; I rode in the control car of the Los Angeles. We cruised around, went down over Atlantic City, climbing gradually until we got up to 3,000 feet. Then, as the dirigible headed back towards the air station, I went back amidships, and there was a ladder which I climbed down to get into the cockpit.

Doctor Mason: You must have had to wear heavy clothing.

Captain Barnaby: Yes. I couldn't wear too much clothing, because there wasn't room enough in the cockpit for too much. I had on a summer flight suit and a leather jacket over that. Probably had a sweater on under the flying suit too.

When I was down in the cockpit, I could talk to Bolster, who was just up in the hatch above me. After I was all set, I asked him to tell the crew to go ahead with the ship. See, they'd stopped the engines while I was climbing down to make it a little easier for me. I wanted them to speed up the engines, and I would let him know when I was reading 40 miles an hour on my airspeed indicator. So it proceeded that way, and when I got my airspeed up to 40 knots, I told Cal to tell them to hold that speed till we got to where they wanted to launch me. Then, when they got over the station, they gave Cal the signal and he started a countdown and pulled the lanyard.

Doctor Mason: What direction were the winds on that occasion?

Captain Barnaby: The wind was out of the west, and it was a light wind. I don't think there was more than, oh, 10 or 12 knots.

Doctor Mason: That would have blown you towards the ocean, wouldn't it?

Captain Barnaby: Yes, but we were headed towards the station, headed into the wind, and I told Cal when to release me. I told him, "Okay, go ahead." He gave me a ten count and pulled the lanyard. You remember the first test flights of these supersonic X-15 planes that they experimented with out at Edwards Air Force Base. They were flown first as gliders without their engines.[2] They were released at 45,000 feet from under a B-52. Someone said, "You mean to say that they released this man in a plane that had never been flown before, with no power?"

I said, "Yes."

"It seems terrible. How do you think he'd feel?"

I said, "I think I know how he'd feel, because some 30 years ago I went through the same experience sitting in a glider with no power under the Los Angeles."

He said, "Well, what did you think about?"

I said, "I sat there thinking, 'How the hell did I ever let myself get maneuvered into this situation?'"

Actually, the instant I was released, I felt perfectly happy. The only thing was that I stuck the nose down and got away from under the ship, because there were two big 18-foot propellers out in front of me and two behind me that seemed kind of close. Actually, I had no worry because she dropped away fast. I leveled off possibly 100 feet below the ship, and then it was just a nice ride down, but awfully cold. It was about 13 minutes coming down, which added over 50% to my total flying time.

Doctor Mason: Yes, I can see. You had 20 minutes total before this. What about the speed of the descent?

Captain Barnaby: Well, 13 minutes for 3,000 feet.

Doctor Mason: That figures into how much miles per hour?

Captain Barnaby: I don't know, that's too much arithmetic for me to figure in my head. I could have stayed up longer if I hadn't been so cold. I just flew at a comfortable gliding speed. I made no attempt to hunt out up-currents and try to soar.

Doctor Mason: Why was it conducted in the middle of the winter? Why not wait for a nice balmy summer day?

Captain Barnaby: That's what the people said down at Kitty Hawk in 1963, on the 60th anniversary. It was about 20 above zero that day with a 20-knot wind blowing off the sea. "Why couldn't the Wrights have made their first flight in the summertime?" Things always seem to work out that way. Admiral Moffett had the idea in December and said, "Let's get to it and do it." That was the only reason.

Doctor Mason: Was the Navy elated at the success of this flight?

Captain Barnaby: I think so. I think they were very pleased at the publicity they got from it. I had the whole cover sheet of the rotogravure section of The New York Times, than which there was none richer in those days.[3]

Doctor Mason: That's right. Was it an experiment that was repeated?

Captain Barnaby: Yes. Only once. Again on the 4th of July down over Anacostia in Washington.

Doctor Mason: Again with the Los Angeles?

Captain Barnaby: With the Los Angeles. Lieutenant Tex Settle, who was later Vice Admiral Settle and is now Vice Admiral Settle (Retired), was the pilot in that launching.[4]

Doctor Mason: Captain, getting back to my question which caused laughter on your part: why was the Navy interested in gliders in the first place? Was it only because of the publicity or what?

Captain Barnaby: Well, there was an idea—also Admiral Moffett's—that it could be put to a practical use. They carried on these large rigid airships a landing officer in case a landing was to be made at a place other than a Navy lighter-than-air base. I think that was true of all the rigid airships; even the German rigid airships carried a landing officer. It was customary for any airship that was going to land at a certain field away from a regular airship base. They'd fly over the field, and this officer would parachute down. It was his job to organize and direct a landing crew. By pre-arrangement, I guess they would get the fire department, the police department, the Boy Scouts, the Rotary Club, and whatnot. They would gather people, and it was his job to explain what the functions were, because handling one of these big rigid airships was a tremendous job, particularly if there was any wind running. Wind altered the time.

Doctor Mason: I can appreciate that. I know what it was handling the Goodyear, a small one.

Captain Barnaby: Well, you can imagine one of these huge rigid ones. And it was the thought that possibly they could release the glider for this purpose. Say they'd be cruising along at 6,000 or 8,000 feet. This glider would have a flat glide angle and would be able to make good—even with some maneuvering—ten to one, anyway. So from 6,000 feet, you'd have ten miles to go. He could release and proceed on and land at the field in his glider without the airship having to make a pass over the field first. The airship could lay off until he would go down and land where he wanted, which wasn't always true with the parachutes in those days. Now they have the steerable parachutes that you can land pretty well where you want. He could go down, using the glider, and organize the landing crew, and that was the purpose.

[1] The conference led to the London Naval Treaty, signed in April 1930. It extended the terms of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty for another five years and also established cruiser tonnage ratios for the United States, Great Britain, and Japan.

[2] The rocket-powered X-15, built by North American Aviation, was the fastest manned aircraft ever flown. It was first airborne in March 1959 but not released from the mother plane. The first independent flight, in June 1959, was made with the engines shut off. The first powered flight was on 17 September 1959. The X-15's highest speed was 4,534 miles per hour in October 1967; the highest altitude was 354,200 feet in August 1963.

[3] Barnaby's flight was reported in a front-page story in The New York Times, 1 February 1930.

[4] Lieutenant Thomas G. W., USN.

About this Volume

Based on an interview conducted by John T. Mason Jr. in August 1969, the volume contains 49 pages of interview transcript plus an index. The transcript is copyright 1995 by the U.S. Naval Institute; the interviewee placed no restrictions on its use.