A recent Proceedings article identified four “schools” of classic American foreign policy— Hamiltonian, Wilsonian, Jeffersonian, and Jacksonian—and how naval forces would align with each. A fifth possible addition would be a Corbettian school: focused on allies and partnerships, sea power, and the common benefits of having secure global commons. The current U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) and National Defense Strategy (NDS) have set priorities to structure national efforts. At their core is a logic familiar to great maritime powers stretching back to the Athenian age: the assurance of political, economic, legal, and military security, and the continued prosperity of citizens at home and allies abroad. The current administration seeks to confront the complexities of these challenges through focused efforts of integrated deterrence and using the strengths of the U.S.-led liberal international system to maintain freedom of the global commons, including free seas. This is a fundamentally Corbettian strategy.

Progressive Strategies

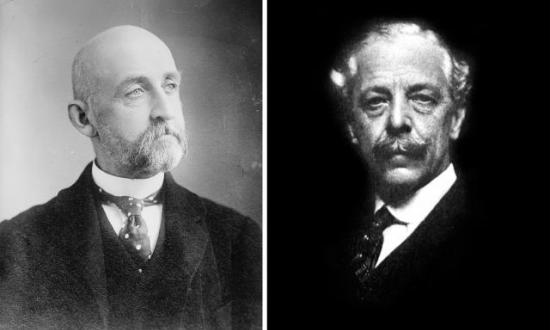

Sir Julian Corbett understood that the grand strategies of progressive hegemonic states must go beyond conservative military approaches that concentrate their efforts on purely military engagements and absolute control of the commons. Rather, he “stressed deterrence above war” and that the priority of great maritime nations must be to push back “against the offshore interests of” revisionist “continental powers.”1 It is a strategy formulated for ensuring, deepening, and broadening a liberal status quo in which allies and partners disperse their energies to deny revisionists. Corbett’s maritime grand strategy is thus a logical progenitor of the current administration’s approach to deterrence and international order. Its focus on progressive liberalism at home and abroad, the importance of international law and economic interdependence, and the subservience of military to national strategy make Corbett the maritime theorist most applicable to the purposes set forth in the 2022 National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategies.

Corbett developed his theories in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for a nation in discord. More so than the uniformed thinkers of the era, he “applied precision and logic to contemporary arguments . . . that addressed the security needs of a global maritime empire in an age of uncertainty.”2 He rejected conservative dogma that defined strategy as a nihilistic clash of military interest. Instead, he identified the uniquely progressive features that had allowed his country to prosper for so long. “Standing outside service tribalism . . .he adapted distinctive strategic traditions to service the agendas of . . . Liberal” policy makers.3 Just as successful maritime strategy must influence the lives of subjects on the land, Corbett identified that a liberal democracy’s ultimate foreign policy aim is to protect and increase the freedoms that its citizens enjoy at home. The current administration’s strategies echo this fundamental principle. The 2022 U.S. National Security Strategy states that, “The quality of our democracy at home affects the strength and credibility of our leadership abroad—just as the character of the world we inhabit affects our ability to enjoy security, prosperity, and freedom at home.” Political scientist G. John Ikenberry succinctly explains that “Biden’s domestic renewal program serves his international [ends]” and “aims to reverse a rising, global illiberal . . . tide by deepening and modernizing liberal democracy.” Once again, the logic can be traced back to Corbettian strategic thought. Autocratic governments that seek antiquated, reactionary solutions to the complex challenges and advances of a new century steer the world to danger. Thus, 20th century Europe sailed to conflict.

Modern Conflict, Modern Thought

Corbett identified the need to modernize the British imperial empire just as a militaristic, continental-minded Germany sought to reshape Europe to its benefit. America today confronts a similar adversary. While the world order evolved from Corbett’s great maritime commonwealth led by the United Kingdom to the rules-based, liberal international order spearheaded and managed by the United States, revisionist continentalists have threatened progressive domestic politics and international free trade. The 2020s have further aggravated the tectonic plates of this order. During his campaign for presidency, President Biden identified the threats posed by China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, and prescribed a joint approach. “The most effective way to meet [these challenges] is to build a united front of U.S. allies and partners to confront” competitors. “On its own,” the NSS continues, “the United States represents about a quarter of global GDP. When we join together with fellow democracies, our strength more than doubles . . . That gives us substantial leverage to shape the rules of the road . . . so they continue to reflect democratic interests and values.”

Corbett would approve. Understanding that “sea power, diplomacy, and money” were the sharpest tools of maritime strategy, he stressed the need for like-minded states to share the responsibility of maintaining the status quo.4 To remain dominant, the United States’ “alliances and partnerships” must remain the “center of gravity” of an open, liberal order. The current administration has focused on strengthening and deepening the United States’ alliance network, specifically in response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

Corbett’s approach stresses the controlling elements of like-minded nations in partnership to establish sufficient sea presence. Today, this approach would allow the United States to maintain efforts in Europe while simultaneously working with Indo-Pacific partners to ensure China and the People’s Liberation Army Navy do not have free reign in the South China Sea. According to Elbridge Colby’s “strategy of denial,” the United States must shift its efforts and resources to focus solely on China. While a convincing argument, it falls short when applying Corbettian logic, and does not allow for the United States to maintain its place in the international system. If conflict is in fact a duel between two forces grappling for the advantage, it follows that each would seek to exploit its opponent’s vulnerabilities to seize initiative and control. A key vulnerability for China and Russia is their lack of military and political allies. A partnership approach in confronting these adversaries, therefore, is logically sound. Dispersed units integrated and networked with partners in the Indo-Pacific and the Mediterranean, Baltic, and Black Seas can manage the threats from each region simultaneously. A Corbettian approach resembles interconnected networks of alliances, with the United States as the central hub, very similar to how the United Kingdom positioned itself in the 18th and 19th centuries.

These networked partnerships are vital to the West’s success. While many argue that the current administration has failed to properly deter Russia or confront China, they do so with a premise of continentalism. Deterrence through partnership has proven effective against an aggressive Russia. The current administration prefaced its posture by clearly stating that Russia would suffer the economic and political consequences wrought by a coalition of partners representing more than half the global economy if it proceeded with an invasion of Ukraine. It accepted that Russia could continue its aggression. In turn, the United States has effectively led, strengthened, and expanded the coalition and followed through on its economic punishments. The direct military option of U.S. forces engaging the Russian military in Ukraine was always off the table, but military force was promised if Russian aggression carried over to neighboring NATO countries. For all the posturing, Vladimir Putin has not seriously attempted to confront Russia’s other democratic leaning neighbors.

Corbett identified that progressive hegemons retain and deepen their relative power not “only [through] brute strength but also [through] ideas, institutions, and values that are complexly woven into the fabric of modernity.” More than militarization and wanton expansion, the British Empire was, and the U.S.-led order is, a broad, “multifaceted political formation” that has allowed a great majority of the world to prosper within an international ecosystem protected by an alliance of a liberal security apparatus. The stability of the global order demands a strong, capable navy integrated and networked with like-minded maritime partners. It is an order that appeals to and benefits nations “shaped by progressive liberal values.”5

However, while the current U.S. National Security Strategy talks extensively about the domains of cyber and space, the word “Navy” appears only once in the document. The National Defense Strategy does not include the words “navy” or “naval” at all. A true Corbettian approach would be more explicitly supportive of the Sea Services and naval policy and encourage a larger naval force. While moving in the right direction, the current administration should remember Corbett’s lessons when approaching national security and international relations. There is more to be done, and the Sea Services must be at the center of U.S. national security strategy.

1. Andrew Lambert, The British Way of War: Julian Corbett and the Battle for a National Strategy (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021), 275.

2. Lambert, The British Way of War, 159.

3. Lambert, 159.

4. Lambert, 128.

5. Lambert, 128.