In late 1942, famed artist Anton Otto Fischer began serving in the U.S. Coast Guard Reserves with the rank of lieutenant commander. In early 1943, he was activated and received temporary orders to a 327-foot Coast Guard cutter moored in Boston. The Coast Guard assigned him to produce illustrations of convoy and combat duty. Fischer agreed to serve as special artist to Life Magazine during this assignment and boarded the battle-tested cutter USCGC Campbell (WPG-32).

(Public Domain)

Serving on board a ship facing the gales of the North Atlantic was no novelty for Fischer. Born near Munich in 1882, he was orphaned as a small boy and ran away to sea when he was 16. For more than five years, he sailed before the mast, working on ships coasting through the Black Sea and Mediterranean, and sailing the high seas through the Atlantic around Cape Horn and up the Pacific Coast.

By 1904, Fischer had decided to leave behind life at sea and become an artist. In 1905, he worked in New York for renowned painter and magazine illustrator A. B. Frost. In 1906, Fischer traveled to Paris with savings of $600 and studied art and painting for two years. He returned to the United States and became a student of famed artist and illustrator Howard Pyle before establishing his own reputation as a book and magazine illustrator. For many years, Fischer’s artwork graced the pages of Harper’s Weekly and The Saturday Evening Post. He became known as a specialist in maritime scenes through his illustrations for numerous books, including Moby Dick, Treasure Island and 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, as well as several books by famed author Jack London.

During World War II, the U.S. military was concerned about the accuracy of imagery used for propaganda and recruiting. Fischer’s love of maritime subjects and his photorealistic painting style got the attention of the wartime Coast Guard Commandant, Vice Admiral Russell Waesche. Fischer spoke English with a thick German accent, and the Coast Guard Intelligence Office had misgivings about him posing a wartime intelligence risk. However, the same day he met Waesche, Fischer was commissioned into the Coast Guard Reserves as the Coast Guard’s official recorder of the war at sea.

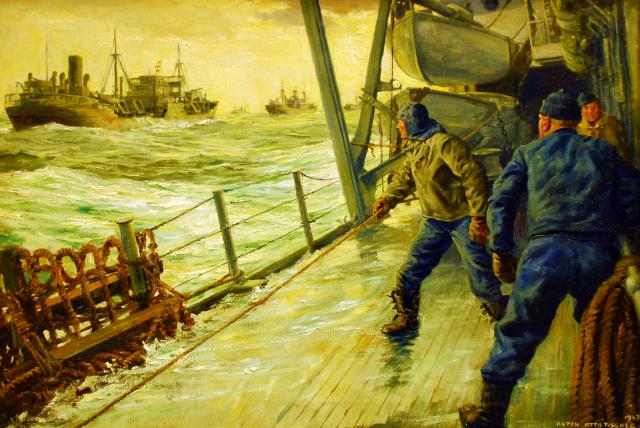

Steaming under Coast Guard Commander James Hirshfield (later Assistant Commandant), the Campbell departed Boston to escort a convoy from the East Coast to the United Kingdom. On board the cutter, Lieutenant Commander Fischer soon became one of the crew. His skill as a poker player and love of cigars and the New York Yankees brought him as much attention as his artwork. During this time, he began sketching scenes of convoy life on the cutter and rediscovered his sea legs in weather that kept many of his Coastie shipmates belowdecks.

During his temporary assignment to the Campbell, Fischer witnessed one of the most dramatic battles between a Coast Guard cutter and a U-boat wolf pack. In mid-February 1943, the Campbell, her sister cutter Spencer (WPG-36), and other warships were assigned as escorts to Convoy ON-166, returning from the United Kingdom to the United States. Within days, as it steamed through the North Atlantic, a German wolf pack of more than a dozen U-boats pounced on the convoy.

Late on Sunday, 21 February, the convoy’s command dispatched the Campbell to assist a torpedoed tanker left behind by the fast-moving convoy. When the cutter arrived, the Campbell found the ship still afloat, with its 50 crew members in lifeboats. Suddenly, the lurking U-boat U-753 loosed a torpedo at the cutter. The Campbell dodged the torpedo, chased down the U-boat, and damaged it so badly it had to withdraw from the battle. The cutter returned to the tanker, picked up her crew, and shelled the vessel’s bridge to ensure destruction of classified documents left behind during the rush to abandon ship.

As the evening darkness set in, the Campbell began to close the 40 miles separating her from the convoy heading east. En route to the convoy, the Campbellencountered more German subs. By midnight, the cutter had singlehandedly damaged or driven off a half-dozen U-boats.

When she rejoined the convoy, the Campbell engaged yet another U-boat, later identified as U-606. By the time Campbell had encountered U-606, the sub already had sunk two ON-166 merchant vessels and damaged a third. In the process, the U-boat had sustained damage from depth charging, so U-606’s captain surfaced hoping to inflict more losses with a daring surface attack within the convoy.

The Campbell steamed directly at U-606 to ram it. The cutter struck a glancing blow to the sub and dropped two depth charges beside her. The explosions lifted the U-boat out of the water; however, the glancing blow also had gashed the cutter’s hull below the waterline near the engine room. The Campbell fought on as her engine room began flooding. The cutter’s crew brought searchlights and heavy weapons to bear on U-606 and dueled with the Nazi predator on the surface.

While the Campbell’s gun crews battled U-606, the rest of the crew raced against time to staunch the flooding in the engine room. The cold salt water finally reached Campbell’s electrical system, shorting the ship’s circuits and dowsing the searchlights. Luckily, by the time the cutter lost power, the U-boat’s crew had been decimated and the submarine rendered defenseless. The German commander ordered U-606 abandoned, and the Campbell’s guns ceased fire. The disabled cutter lowered her boats and found only five surviving submariners.

After the battle, the Campbell’s crew continued the struggle, only this time it was for the very survival of their cutter. Commander Hirshfield believed he might lose his ship, so he transferred the German prisoners, the 50 tanker crew members, and all non-essential cuttermen to other vessels. The cutter sat powerless in the open ocean while the convoy pressed on to the United States. After wallowing in the North Atlantic for four days, the Campbell received a tow to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and returned to duty after repairs.

In March 1943, less than three months after his activation and deployment, Fischer returned to reserve status. While serving on board the Campbell, Fischer had sketched many scenes he later reproduced on canvas. He returned to the studio at his home in Woodstock, New York, where he painted the sketches for the Coast Guard. Many of these World War II works are held in the Coast Guard’s Heritage Art Collection, and a sampling of them are featured with this article.

In 1945, Fischer returned to civilian life. After a prolific career as a painter and illustrator, Anton Otto Fischer passed away in 1962 at his home in Woodstock. He was laid to rest nearby in Kingston, New York, alongside his wife and fellow artist, Mary Ellen Sigsbee Fischer, who had passed away two years earlier. Lieutenant Commander Fischer was the only professional artist to witness firsthand the violence of a wolf pack attack in the Battle of the Atlantic—and to reproduce these dramatic images in color on canvas.