The Navy’s role in the Civil War is underappreciated by both historians and the public. While a few names from that conflict are fondly remembered, John Rodgers lies in obscurity. This discredits Rodgers’ essential service. No other officer had as much to do with the widespread adoption and employment of ironclad vessels. He was directly involved in the design of two ship classes, captained a poorly designed prototype through a hellish combat debut, led a monitor to victory in a decisive ship-on-ship engagement, and shepherded the lead ship of an ocean-going class of monitor into service. He emerged as one of the most seasoned and forward-thinking officers in the Navy, and the one who did the most to successfully midwife the idea of ironclad warships to win a war.

An Unorthodox Officer

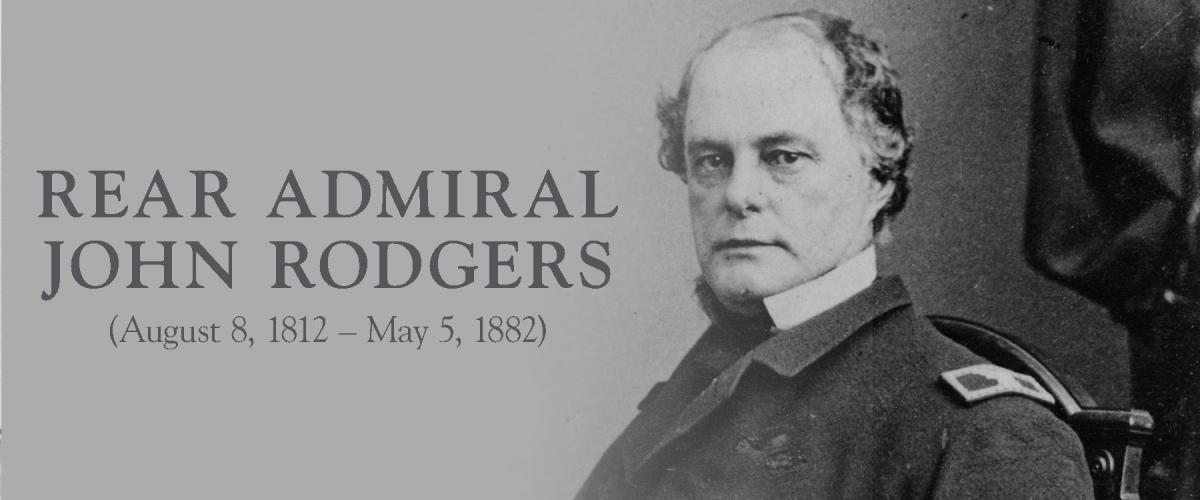

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

John Rodgers was born in 1812 in Havre de Grace, Maryland, to Commodore John Rodgers and his wife, Sarah C. Perry Rodgers. The elder Rodgers was a hero of the early Navy, led a squadron during the War of 1812, was President of the Board of Navy Commissioners from 1815–24 and 1827–37, and was senior officer of the Navy from 1821 until his death in 1838.1 Raised in Washington, the younger Rodgers entered the Navy as a midshipman at the age of sixteen. Following service in the Mediterranean, he passed for lieutenant in 1834 and attended the University of Virginia from 1834–5. His studies included mathematics and natural philosophy (engineering).2 In the era before the establishment of the Naval Academy, this made Rodgers one of the few college-educated officers in the Navy. He returned to active duty and served during the Seminole War as a boat commander in the “mosquito fleet” that operated in the littorals and swamps of south Florida.

Rodgers was a proponent of steam engines and did protype work on several ships as the Navy began to incorporate their use into the fleet. Eventually, he was assigned to the U.S. Coast Survey and later commanded the North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition. This service gave Rodgers an intimate knowledge of coastal and riverine service, as well as some of the most extensive experience with steam plants of any line officer in the Navy going into the war.

The War on the River

Serving in Washington at the beginning of the Civil War, Commander Rodgers was part of the hastily assembled team sent to affect the evacuation of Gosport Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth, Virginia. He attempted to destroy the drydock there, but ultimately could not complete the mission. Rodgers was captured, but as Virginia had not yet joined the Confederacy, he was sent through the lines. Ironically, the failure to destroy the drydock meant that Rodgers would also contribute directly to the creation of the Virginia, as she was converted from the wreck of the Merrimack there.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

On 16 May, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles directed Rodgers to Cincinnati to report to Major General George B. McClellan, then commander of the Department of the Ohio, to assist him in creating a force for service on the western rivers.3 This would eventually become the Mississippi River Squadron, which was led to acclaim by Andrew Foote and David Porter in 1862–64. In his directions, Welles indicated that the Army was responsible for operations on the western rivers, a decision that would leave Rodgers caught serving two masters and eventually leave him in an untenable position. However, McClellan did not want Rodgers simply for his advice, but rather thrusted the whole issue of riverine warfare into his lap.4 This relationship, as a service commander under a combined combatant commander, was unusual and well ahead of its time when the War and Navy Departments were separate.

Welles intended for Rodgers to go to Cairo, Illinois, to oversee construction of gunboats, but Rodgers instead went to Cincinnati to begin coordinating with McClellan. There, working with Naval Constructor Samuel Pook, he acquired and began the conversion of three riverboats into gunboats as a stopgap measure to fill the immediate need. His industry would not only cause the beginnings of friction with him and the Navy Department but also would produce the “timberclads.” These gunboats would prove successful beyond all expectations and serve throughout the war, with none lost to enemy action, despite many engagements. Rodgers and Pook lowered the boilers, rerouted the steam lines, and provided timber armor to harden the Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga. On learning of it, Welles reprimanded Rodgers for spending money without authorization, as the Army was responsible.5 However, McClellan quickly assumed responsibility for the contracts. This put the matter to rest for the moment, but despite McClellan’s satisfaction with Rodgers’ work, the seed was already planted in Welles’ mind that Rodgers may not be the man for the job.6

Rodgers was quickly on the move to find and survey armaments for these gunboats and the new class that he was to oversee. Finally arriving in Cairo, he met with Pook, who had arrived at a preliminary design of ironclad gunboat after discussions with James Eads, a famed riverine expert and naval architect. This was the origin of what was to become the City-class gunboats, the first ironclad ships to see action during the war. Rodgers selected the type of iron used in the armor, altered the design of the wheel house, set the armament, improved the design of the armor joints, and increased the wooden armor backing in the forward part of the ships.7 The finished product was an important evolutionary step in the development of ironclads, combining very shallow draft, paddle wheel propulsion, medium armor forward, and heavy armament of five rifled 42 pounders and ten 9-inch Dahlgrens. However, the ships were thinly armored aft, which left the boilers exposed on their quarter and stern. In addition, they were underpowered, making them slow sailors. Despite their flaws, the seven gunboats of the City class would be the backbone of the Mississippi River Squadron, winning distinction for their toughness and versatility.

While he was finalizing the design of the ironclads, Rodgers was also dealing with getting the timberclads down the Ohio and into service, recruiting rivermen for service in the squadron, and a change of command. McClellan was promoted and left for Washington in late July, leaving Major General John Fremont in his place. Fremont, the famous western explorer and failed Republican presidential candidate, did not like Rodgers. Partly, this stemmed from Fremont’s feud with Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, Rodgers’ brother-in-law, over Fremont’s refusal to follow Quartermaster Department purchasing procedures. Fremont and Rodgers also disagreed on a proposal by Eads to convert his Submarine No. 7 into a gunboat. Rodgers did not approve of the plan, but Fremont overrode him, and the boat eventually entered service as the Benton, a larger version of the City class.8

Within two weeks of assuming command, Fremont had written to a member of the Cabinet to have Rodgers removed. In late August, Welles assigned Captain Andrew Foote to proceed from New York to St. Louis to assume command.9 Rodgers could not remain even as Foote’s second in command, as two more senior commanders soon joined the squadron, so Rodgers returned to Washington in October for further duty after only four months in command. In that time, Rodgers had been the driving force to bring the ten gunboats into service that would form the backbone of the Mississippi Squadron. His partnership with Samuel Pook was short-lived but highly productive. Despite a sterling combat record ahead of him, he had already done the most to bring about victory in the war that he would.

“… she is not Shotproof.”

Rodgers immediately got himself back onto active service. He was given command of the Flag, a merchantman converted to a gunboat. He transited to this command as a temporary member of Samuel Du Pont’s staff, playing a crucial role in creating the attack plan for the assault of Port Royal Sound, South Carolina. He then joined his ship off Savannah, Georgia, for blockade duty. Falling back on his pre-war experience with the Coastal Survey in the area, Rodgers conducted numerous reconnaissance missions and played a major role in seizing Tybee Island. He commanded his first squadron here, trying to interdict traffic between Savannah and Fort Pulaski. In early 1862, he took the Flag to Washington for badly needed repairs. After his stellar service in the past few months and his experience on with the ironclads in the west, Rodgers was slated to command the Galena, one of the three prototype ironclads accepted by the Ironclad Board in 1861.

The Galena was truly an “ironclad” with a layer of three-and-one-eight-inch iron plating over her wooden hull. The Galena was intended to be lighter, faster, and more maneuverable than either the Monitor or the New Ironsides, the two other selections of the board. Originally rigged as a foretopsail schooner, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough ordered her masts removed for service on the James River.10 Rodgers was disappointed in his new ship, commenting, “I do not think she fully comes up to the idea of an iron-plated craft.”11

On 8 May, Rodgers—in command of a squadron consisting of the Galena and the wooden gunboats Aroostook and Port Royal—attempted to force a passage on the James River, clearing out much of the lower river. However, the defenses grew stronger closer to Richmond, and Rodgers requested reinforcements. With the destruction of the Virginia on 11 May, the Monitor and the USRC Naugatuck (an experimental submerging ironclad the Navy had refused but the Revenue Service had accepted) joined Rodgers’ squadron. The only remaining fortification between them and Richmond was also the most formidable—Fort Darling on Drewry’s Bluff.

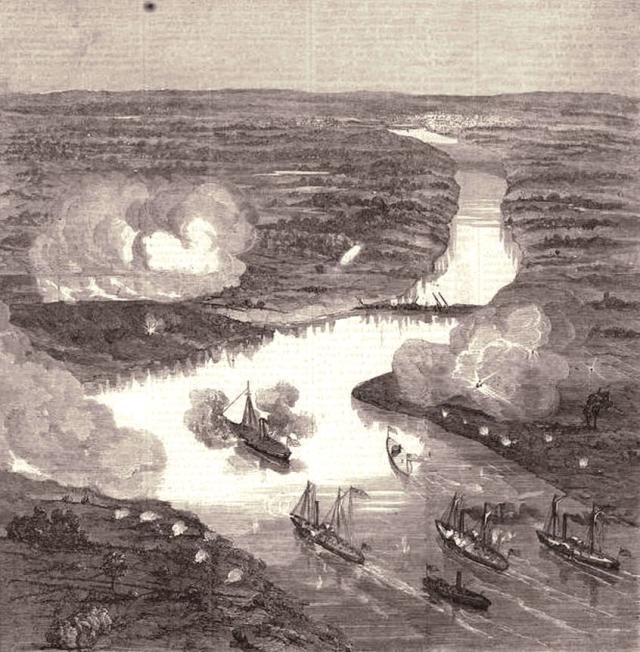

(Harper's Weekly)

The fort was situated on top of the 100-foot bluff, commanding the channel, which was obstructed. Rifle pits lined the river, preventing parties from removing the obstructions. The Confederate James River Squadron was drawn up behind the obstructions as a further defense. At 0745, Rodgers anchored the Galena and opened fire.

The Monitor could not raise her guns enough to hit the bluff and was ordered out of range while the Galena and the Naugatuck continued to fire at the fort. The Naugatuck’s gun exploded, leaving the Galena alone. For over four hours, Rodgers kept her engaged, expending all but a few rounds of ammunition. Heavy shot and shell ripped into the ship time and again, punching through the armor, knocking planks and structural supports out of place. At 1105, after the Galena had been struck more than 40 times, the squadron withdrew in the face of the superior fire. Thirteen men were killed on the Galena, with another eleven wounded. Rodgers’ report detailed the damage:

The result of our experiment with the “Galena” I enclose. We demonstrated that she is not Shotproof. Balls came through and many men were killed with fragments of her own iron. One fairly penetrated just above the waterline and exploded in the steerage. The greater part of the balls however at the waterline after breaking the iron stuck in the wood.12

Despite the heavy damage, the Galena remained on station throughout the summer, supporting the Peninsula Campaign. Rodgers was promoted to captain in July, and in November, Secretary Welles acceded to Rodgers’ request to be given one of the first production class of monitors.

Showdown in Wassaw Sound

Rodgers took command of the Weehawken before her commissioning. The new Passaic class was an improved version of the original Monitor—slightly larger, more heavily armed, and with improved machinery. Rodgers took advantage of the time to observe the sea trails of the Passaic and get a good understanding of how his new ship would handle. When the Weekhawken’s engineer proved incompetent, he brought aboard James Young, his engineer from the Galena. Leaving New York, Rodgers brought his ship safely into Chesapeake Bay through a gale with over 30-foot seas. Rodgers received acclaim from Welles on down for his seamanship and fortitude for this, as the Navy’s leaders assumed the ship had floundered.13

In April 1863, Welles directed Admiral Du Pont to launch a naval attack on Charleston, despite Du Pont advocating a joint operation.14Weehawken, pushing an experimental minesweeping apparatus against the numerous mines the Confederates had sown, was the lead ship in Du Pont’s attack. The squadron was entirely made of ironclads—seven Passaics, the experimental Keokuk, and the large New Ironsides—attacking in a single column. Rodgers had submitted his own attack plan based on his Drewry’s Bluff experience in which the ships would stay at 1,250 yards, where their small size and armor would keep them safe, but their heavier guns would still be effective. However, Du Pont opted for a close attack at 600–800 yards to save wear on the untested 15-inch Dahlgrens of the Passaics.15

The attack itself turned into a fiasco. Rodgers chose to deviate from the attack plan when he encountered a thick line of floating casks, which he took to be mines. Already worried about fouling the propeller if he pushed through them, a mine exploded close aboard. All the Union ships had trouble with the strong current and the New Ironsides lost steerage. Numerous batteries opened fire on the squadron, smothering the ships in shot and shell. The Weehawken was struck at least 53 times during the furious two-hour assault. Iron armor came loose, the turret stopped working, and there was a hull breach. The volume of fire was too much for the Union ships, who only fired 151 shots to the 2,209 fired by the rebels. More than 500 of those were hits, validating the plan Rodgers had forwarded.16

In early June, Rodgers took the Weehawken and the monitor Nahant to Wassaw Sound near Savannah in response to intelligence that the Atlanta, the most powerful ironclad the Confederacy produced, was going to breakout to open water. Built from the iron-hulled blockade runner Fingal, the Atlanta was fast, and powerfully armed with Brooke Rifles. Rodgers chose the confined, shallow waters of the sound as his battlefield to keep the deep-draft Atlanta confined and unable to use her superior speed. He established a picket boat on the channel from Savannah and waited.17

On 17 June, Commander William Webb brought the Atlanta into the sound. The picket sounded the alarm and the Federals beat to quarters. The Weehawken got underway ahead of the Nahant, who would not play a part in the battle. The Atlanta ran aground, and Webb desperately tried to get the ship afloat, and was successful only to have it immediately ground again. Both sides opened fire, and only exchanged twelve rounds. All seven shots from the Atlanta missed, but three of Rodgers’ five shots found their mark. He pushed the Weehawken within 300 yards and circled the immobilized enemy. The 15-inch Dahlgrens cracked the thick iron and wood armor, wounding half of the Atlanta’s gun crews as well as her pilots. Aground, unable to return fire, and full of wounded and stunned men, Webb struck his colors after fifteen minutes of combat.18 Following the action, Rodgers forbade his men to cheer as Webb came aboard to surrender his sword, calling out, “Poor devils, they feel badly enough without our cheering.”19

The news of this decisive victory brought Rodgers instant fame. Congress voted him its thanks and he was promoted to commodore. He commanded the lead ship of the new Canonicus-class before sickness made him relinquish command. He then was assigned the lead ship of a class of ocean-going monitors, the Dictator. She was far larger, deeper draft, and heavier than other monitors, and designed for speed. Rodgers spent the rest of the war dealing with technical difficulties with the ship’s drivetrain, trying to get her to sea. He frequently consulted with the Navy Department on ironclads and was considered for a flag command at the end of the war. However, Wassaw Sound was his last active role.20

He had proven himself a popular commander, who was loved by his men, but Rodgers remained humble. Writing to his wife, he expressed his views on his leadership, “I love to give credit where credit is due . . . I do not care for popularity—and I make no effort to attain it . . . as I am amiable, fair, and I hope efficient enough to command respect, popularity has come I think as a matter of course.”21

Following the war, he commanded the Boston shipyard prior to his promotion to rear admiral and command of the Asiatic Fleet. He led the Korean Expedition in 1871 in an effort to end Korean isolation and open U.S. trade there. He later commanded the Mare Island Shipyard before becoming superintendent of the Naval Observatory in 1877. In 1879, he was elected third president of the U.S. Naval Institute. He died in 1882 while still on active duty at the age of 69.

The Ironclad Expert

Rodgers’ war service put him in some of the more important naval battles of the war, and he gained a reputation for being a fearless and hard-driving commander. It also gave him the opportunity to influence the design and use of the cutting-edge technology of steam-driven ironclads more than any other officer below Secretary Welles. Despite his difficulty with Welles in the initial chaos of the war, Rodgers clearly gained Welles’ trust. The timberclads and City class dominated the western rivers and led to victory after victory, proving that Rodgers had made the right choices in his stormy tenure as commander of the Western Flotilla. His bravery and doggedness in taking the Galena into the fire of Fort Darling and battling away despite terrible damage and heavy losses proved his combat leadership and gave credence to his criticisms of that protype. Rodgers was a keen supporter of monitors, but he was not above reporting faults with the various ships of that type he commanded. He also helped develop the tactics for these ships, pushing for longer engagement ranges to maximize the advantages of the ironclads, stating “ironclad vessels are to fight wooden vessels and forts, at distances which leave the ironclads impenetrable to the artillery opposed to them.”22 His professional education, years of prewar steam experience, technical proficiency, and combat acumen gave him a unique and respected view. Those critiques helped improve the Passaic, Canonicus, and Dictator classes into more efficient and capable platforms. Ultimately, no other officer did as much for the Navy to push it into this new and untired technology and to make it the success that led to victory at sea in the Civil War.

1. Robert Erwin Johnson, Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 1812–1882 (Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1967), 7.

2. Johnson, Rear Admiral John Rodgers, 35.

3. Gideon Welles to John Rodgers, 16 May 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, series I, volume 22 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1927), 280.

4. Johnson, 157.

5. Gideon Welles to John Rodgers, 12 June 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion I:22, 284–5.

6. Gary D. Joiner, Mr. Lincoln’s Brown Water Navy: The Mississippi Squadron (Plymouth, UK: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007), 19–20.

7. Johnson, 162.

8. Joiner, Mr. Lincoln’s Brown Water Navy.

9. Fremont to Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, 9 August 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion I:22, 297; and Welles to Foote, 30 August 1861, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion I:22, 307.

10. Johnson, 171–188, 194–5.

11. Johnson, 171–188, 194–5.

12. Report of John Rodgers, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion I:7, 357.

13. Johnson, 223–232.

14. James M. McPherson, War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 140–1.

15. Johnson, 240–1.

16. Report of John Rodgers, 8 April 1863, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion 14, 11–13; and McPherson, War on the Waters, 146–7.

17. Andrew Roscoe, “The Battle of Wassaw Sound: Forgotten Clash of the Ironclads,” Civil War Navy–The Magazine 6, vol. 4 (April 2019), 31–2, 37.

18. Roscoe, “The Battle of Wassaw Sound,” 37–9.

19. Johnson, 256.

20. Johnson, 261–7.

21. Johnson, 221.

22. Johnson, 168.