This fall marks the 30th anniversary of the Naval Institute Press’s first novel, The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy. It put the Press on the map, led to a successful movie, and was the making of a superstar career for Clancy, who died last year at age 66.

Before he was famous, Clancy ran an insurance agency in southern Maryland, not far from the Calvert Cliffs nuclear power plant. Nearsightedness was a problem for years, the reason for thick eyeglasses and the condition that prevented him from serving in the military. What he did possess was a sponge-like mind for details of military hardware. Many of his insurance clients were former nuclear submariners—officer and enlisted—and he picked their brains.

Clancy, who had a degree in English literature from Loyola College in Baltimore, did some writing on the side, including a start on the manuscript of the book that later made him known worldwide. He wrote a letter to the editor and a “Professional Note” for Proceedings, through which he came in contact with Marty Callaghan, an associate editor with the magazine. He told Callaghan about his work in progress: the story of an unhappy Soviet submarine skipper who defected with his ship, was pursued by a vengeful Soviet armada, and finally turned his submarine over to Americans. Callaghan and Proceedings deputy editor Fred Rainbow encouraged him to submit it to the Naval Institute Press.

The next step involved acquisitions editor Debbie Guberti (now Grosvenor), who needed some persuasion to read the story. When she took it along as summertime beach reading, she saw promise. She also observed that it would take a fair amount of work to bring to fruition, because the plot was sometimes confusing. Guberti, intrigued by Clancy’s dialogue and storytelling ability, passed the work along to Press director Thomas Epley, who needed considerable convincing.

The Press had never before published a novel, and the author of this one was an unknown whose prose needed polishing. Epley eventually agreed, and it turned out the timing was fortuitous. Commander R. T. E. “Bud” Bowler, who was nearing retirement as head of the Naval Institute, was a preserver of traditions. There had been a policy of no fiction in the organization’s repertoire, but its Editorial Board had recently approved a change in policy after Proceedings reviewed Jim Webb’s Vietnam novel Fields of Fire. The Institute bought Clancy’s story. The job of turning the manuscript into a publishable volume fell to Connie Buchanan, a superb copy editor. In addition to sharpening the focus of the plot, she trimmed out sections of material that might prove hard going for some readers.

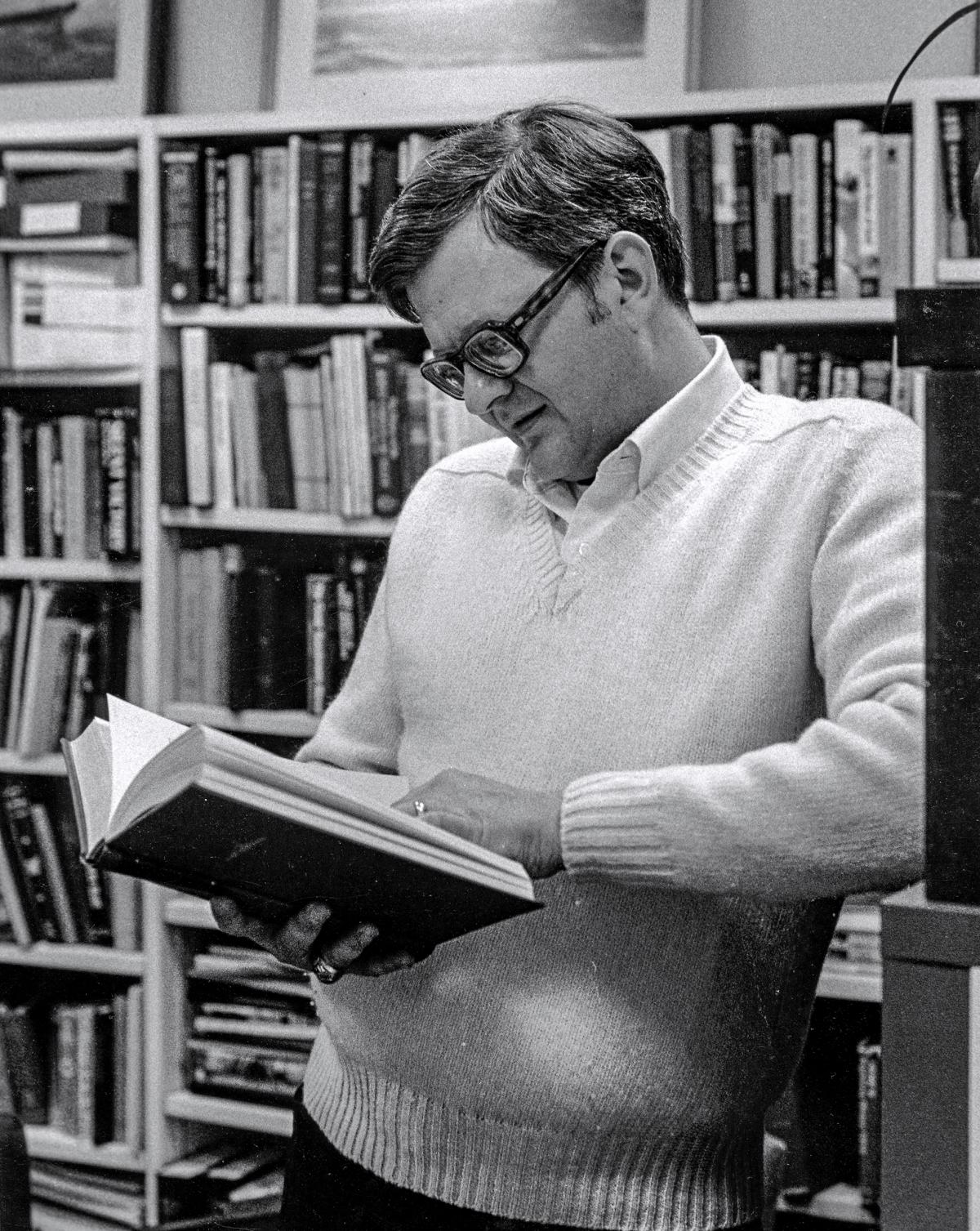

On the front of the dust jacket would be the black silhouette of a submarine with the red hammer-and-sickle insignia of the Soviet Union superimposed. Part of the plan for the jacket called for Clancy to travel to the submarine base in New London, Connecticut, and pose in front of a U.S. submarine. But he and Press marketing director Jim Sutton were turned away at the base—something about security precautions. That led to my own unconscious and minuscule “contribution” to the project. While I was away from the office one day, Sutton and Clancy came to the Naval Institute’s headquarters, at the U.S. Naval Academy’s Preble Hall, and found a backdrop for his photo: the bookshelves in my empty office.

The initial plan was a press run of 5,000 copies. The next task for the Press—in those days long before the Internet and Amazon.com—was to get the novel into bookstores. Chief publicist Susan Artigiani made that happen, generating enough buzz to bump the first run to 15,000. She recruited retired naval officers Admiral Stansfield Turner and Captain Ned Beach to write endorsements.

During her years on the staff, Artigiani had cultivated a network of book reviewers. Favorable comments in Publishers Weekly got booksellers’ attention. She also reached out to Reid Beddow, an assistant editor of the book section for The Washington Post. His praiseworthy review gave the novel a further push. And the scuttlebutt in the corridors of the Institute was that Artigiani charmed a Time magazine writer into doing a full page on Red October. By then the biggest plaudit had already come from President Ronald Reagan, who proclaimed Clancy’s work “the perfect yarn.” That raised the buzz to a roar. More and more printings followed. The book eventually sold more than 300,000 copies in hardcover and more than two million in paperback. Guberti added considerably to the income flow with her sale of foreign and subsidiary rights.

When the book appeared, Captain Jim Barber had taken over as the Naval Institute’s chief officer and publisher. Commander Bowler had left him a great windfall, both in terms of financial returns and in setting a successful precedent for publication of fiction. In September 1986 the press published Stephen Coonts’s novel Flight of the Intruder, an account of the operations of an A-6 attack plane in Vietnam.

The dollars kept pouring in, and Barber decided to use some of the revenue to enhance member benefits, including special issues of Proceedings and, in 1987, a trial issue of Naval History. Enough readers signed up that it went into quarterly publication in 1988 and became a bimonthly in 1993. Tom Clancy’s homework and imagination fueled the creation of the magazine you are now reading.