Marines, ‘Scarface’ Vietnam Veterans Honor a Lost ‘Legend’ Colonel Harry E. Sexton, USMC, 1932–2023

With three former lieutenants providing escort on his final sortie, U.S. Marine Corps Colonel Harry E. Sexton was laid to rest on 10 March in Lake Elsinore, California. It was the final mission of Sexton’s 26-year military career that took him on 400 combat missions in the cockpits of fighter jets and helicopter gunships during the Vietnam War.

Sexton, 90, died 15 February in Laguna Beach, California, where the retired naval aviator raised his children, worked in his family business, and kept a daredevil streak into his 80s, riding his Harley-Davidson with biker friends. Over his 26-year military career, Sexton crossed the skies in fighter jets and helicopter gunships and laid covering fire for U.S. troops in the combat zones of Vietnam.

Few knew he had been awarded the Navy Cross, the nation’s second-highest medal for combat valor, for actions during a secretive 1970 mission, Operation Tailwind, supporting U.S. Army Special Operations Forces tied to then-classified CIA activities in neighboring Laos.

Sexton commanded Marine Light Helicopter Squadron (HSL) 367, which flew AH-1G Cobra helicopters from Marble Mountain Air Facility, the Marines’ air base near Da Nang and the support base for U.S. Army 5th Special Forces Group. Their Tailwind tasking: Lead the mission with a division of “Scarface” Cobras to provide escort and covering fire for Marine Corps CH-53D transport helicopters hauling 16 Green Berets and 120 Montagnards 70 miles deep into enemy-held territory. The company-sized “hatchet force” launched 11 September 1970 to distract from a larger CIA operation to thwart North Vietnamese Army operations and supply lines.

By 13 September, the hatchet force’s casualties were mounting, and calls came for an emergency extraction. “If we didn’t get them out that day, they wouldn’t survive. They had been in combat the whole time,” said Patrick Owen, former copilot of Sexton’s and treasurer of the Distinguished Flying Cross Society.

Sexton led the flights to evacuate the wounded as aircraft took heavy fire. The following day, as enemy troops closed in on the remaining force, the Cobras returned to the scene. Sexton and Owen used smokescreens and rocket and gun fire to provide cover for the five CH-53Ds. Their Cobra took several hits under intense fire but returned to base.

Sexton’s Navy Cross was one of several combat medals awarded to aircrews in the secretive mission. “We didn’t talk about it for 30 years,” Owen said. “He never talked about Vietnam,” said Marine Corps Captain Ian Voss, “but he told great stories about the Marine Corps.”

Sexton often biked 50 miles between his and his daughter’s home and, until a few years ago, awoke at 0400 daily for gym workouts, Voss said. His motorcycling days included road trips to Sturgis, North Dakota, and Laughlin, Nevada, where he found himself in a casino amid a gunfight between the Mongols and the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gangs. “Harry was the real deal—he was the King of Cool,” Voss said.

Voss joined four of Sexton’s wartime lieutenants who gathered by the flag-draped wooden coffin, Marine Corps emblems tacked at each corner. Honor Guard Marines from Marine Corps Air Station Miramar in San Diego honored Sexton with a gun salute before “Taps” sounded.

“I became a Marine because of Harry,” said Voss. In 2007, when he was headed to Iraq on his second combat deployment, Sexton “was keeping me calm,” he said, as he was nervous about heightened threats from roadside bombs. “He told me I would be all right. Just trust my leaders and my training. He then walked around and shook every Marine’s hands, and he said, ‘You’ll be alright. Don’t worry about it.’ Never once did he tell them he was a retired colonel and a Navy Cross recipient. When you become a Marine, you tend to emulate those leaders who are exemplary. Harry was always a leader I wanted to be.”

—Gidget Fuentes

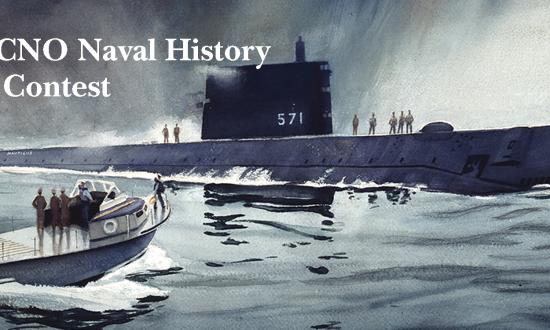

Wreck of World War II Sub Identified as Albacore

The wreck of a World War II–era submarine, discovered by a Japanese research team in May 2022, has been confirmed by the Underwater Archaeology Branch of the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) to be that of the USS Albacore (SS-218), which was lost at sea in 1944.

Commissioned on 1 June 1942, the Albacore conducted 11 war patrols and is credited with ten confirmed enemy vessel sinkings (with possibly another three not yet confirmed). She earned nine battle stars and four Presidential Unit Citations during her career. Six of the Albacore’s ten sinkings were enemy combatant ships, ranking her as one of the most successful submarines against enemy combatants during World War II.

The submarine was last seen when topping her fuel tanks at Midway Island on 28 October 1944. After that, she vanished and, by late December, was presumed lost with all hands.

Japanese records that came to light after the war included the report from a patrol boat of an unidentified submarine striking a mine off Hokkaido on 7 November 1944. Working from that clue, a University of Tokyo research team led by Dr. Tamaki Ura launched a search for the wreckage in May 2022.

The team’s sonar detected a likely wreck site at a depth of 820 feet. A remotely operated underwater vehicle subsequently photographed the wreck, and it conformed to the description of the Gato-class Albacore. Now, the identification has been confirmed by the U.S. Navy.

As a sunken U.S. military craft, the wreck of the Albacore is protected by law and is under the jurisdiction of NHHC. Any activities relating to it need to be coordinated with and authorized by NHHC.

Most important, the wreck represents the final resting place of the sailors who gave their lives in her and thus should be respected as a war grave.