The call came to our headquarters at the Naval Academy’s Preble Hall in mid-1995. It was retired Navy Captain Bill Horn, asking whether I’d be interested in an interview with a Japanese kamikaze from World War II. Without logically pondering the idea, I blurted out “Of course!”

Then it slowly began to sink in. Bill Horn is an intelligent and knowledgeable guy, but I wondered whether somehow he simply had been tricked by a crank caller. If this person were indeed a kamikaze, I wondered, how could he be alive to tell the tale? Captain Horn had the answer.

At the time, Kaoru Hasegawa was president of the Rengo Company, Ltd., an international corrugated packaging producer based in Osaka. On 25 May 1945, he was an officer in the Japanese Special Naval Attack Corps, bearing down for a kamikaze strike against U.S. warships east of Okinawa.

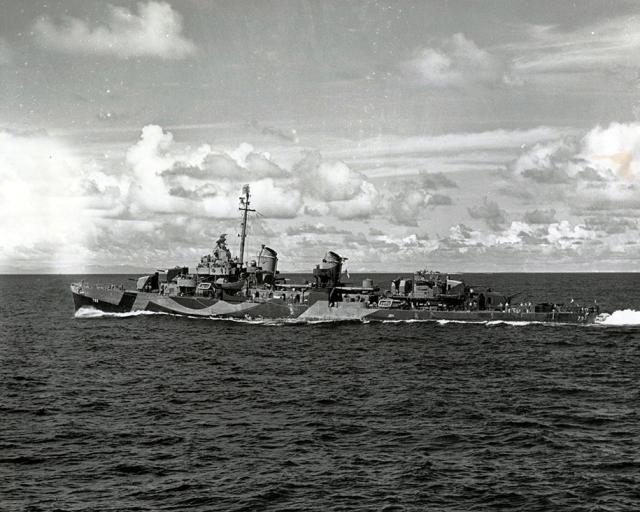

According to research the wealthy box-maker, Horn, and others had done prior to and during Hasegawa’s visit to the United States, at about 1015 that morning Hasegawa’s P1Y “Francis” bomber took a hit from the USS Callaghan (DD-792) and crashed into the sea. The destroyer crew rescued the severely injured navigator (the aircraft’s other two crew members did not survive) and tossed him aside on the deck while they continued the fight. After the combat subsided, the destroyermen transferred Hasegawa to the USS New Mexico (BB-40), where he failed at a suicide attempt (he recalled thinking that he had nothing to live for) before being transferred to Guam. Ironically, a kamikaze attack sank the Callaghan just more than two months later.

In July 1995, the 50th anniversary of the destroyer’s sinking, a wreath-laying ceremony and reception was held at the U.S. Navy Memorial in Washington. There, Hasegawa honored the ship’s dead and her survivors and subsequently was invited to the survivors’ reunion that year in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, where he was welcomed as a Callaghan survivor himself.

From that point forward, Hasegawa flew from Japan to Callaghan reunions until his death in 2004. Perhaps the most memorable story to emerge from those annual gatherings was the time a Callaghan survivor presented Hasegawa with the wristwatch he had been wearing when he was shot down. Moved by the gift, Hasegawa presented the former sailor a new Rolex watch at the next reunion.

As I was conducting our interview for Naval History, a member of Hasegawa’s staff placed a self-winding compact 35-mm camera (high tech for the time) on my office chair as a gift. It would not be the only such gesture the distinguished Japanese businessman would make to my wife, myself, and many others over the years.

Each time Hasegawa visited Washington, he hosted a sumptuous dinner, usually with the same guests, including Callaghan survivors such as Captain Jake Heimark, former executive officer on the ship, and former crewman Leo Jarboe, who lived in the environs of the city. It became a “mini-reunion” of sorts, even for spouses.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

A Hasegawa dinner (he was a connoisseur of French cuisine and fine wine) was always an impressive affair. Guests at various times included former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral William Crowe, former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, former Smithsonian Air & Space Museum Director Vice Admiral Donald Engen, and Mari Christine, introduced to the group as “Japan’s answer to Katie Couric” (referring to the cohost of NBC’s “Today” show at the time).

Kaoru Hasegawa was a generous goodwill ambassador who when he saw me would say “Schultz san!” even from across the room, no matter who was shaking his hand. With fond memories and gratitude for his friendship, following are a few excerpts from our interview.

Naval History: What motivated your visit to the United States and to the U.S. Naval Institute?

Hasegawa: I had asked my friend, Captain William Horn, U.S. Navy (Retired), to confirm the records about my encounter with the U.S. destroyer Callaghan. I have therefore come here to reconfirm my recollection of the past. I am here also for the 50th anniversary of the date—25 May 1945—when I was shot down by the Callaghan.

Naval History: How did you happen to volunteer for the Special Attack Corps?

Hasegawa: The approach to form the Special Naval Attack might have been different between the Army and Navy at that time. I was assigned to the 405 “Ginga” (Galaxy) Corps. It was a natural or normal procedure that, as a lieutenant in the Navy, I would be selected to command the 10th Ginga subunit, which was assigned to the Special Attack on 25 May.

Naval History: Was this simply your duty as a naval officer?

Hasegawa: Normally, there were about 20 officers in a flying unit. Somebody had to be named to command an attack mission. If I had died as a result of a kamikaze attack, somebody else would have assumed command of the next aircraft. So in that sense, it was a normal duty as a naval officer.

We had only 30 airplanes, when we should have had 48 bomber aircraft in our corps. It was a losing war. We were conducting many ordinary attacks. In an ordinary attack, you came back after you completed your mission. In a Special Attack, if you were successful, you did not come back. There was no special sensational feeling that came with our service in the Special Naval Attack Corps, because we had both types of missions. Every day and night we were attacking, and many people were dying. A few days before 25 May, it was decided that the forthcoming mission would follow the Special Attack method.

The 405 Corps had been assigned to carry out many ordinary attacks against Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and the American naval fleet. Some died during the missions. That method or mission procedure was the same as that used by the United States or other countries. Some days before the 25th, we were informed that the day’s attack would be a Special Attack mission. It was not a decision made after special deliberation. One day we would employ the ordinary attack method; the next day we would be alerted for a Special Attack mission. I must emphasize here that the Special Attack mission was not something we regarded as extraordinary. Of course, they were extraordinary tactics. Military men, however, had to follow whatever orders given to them and believed that they should do their best to complete assignments.

Naval History: Did you receive any special training for such missions?

Hasegawa: There was no special training for Special Attack operations. It was not necessary. Any pilot with high skills could perform the mission.

Naval History: Why were kamikaze tactics not used earlier in the war, if they were considered to be so effective?

Hasegawa: One can rationalize many ways to fight a war. The specific tactics that are used vary, and any one tactic might be effective on a certain occasion. But from a broad point of view, I cannot say that an attack succeeded just because it was a kamikaze attack. An ordinary attack could be just as effective. I do not think that kamikaze tactics were so effective, considering the ultimate sacrifice of a human being and an airplane for each “successful” mission.

Naval History: How are World War II kamikaze survivors treated or regarded today?

Hasegawa: There are technically no kamikaze survivors. If you were deployed as a kamikaze and you succeeded, you died. Some survivors who participated in the Special Attack Corps missions are the ones who had turned back while on the way to the original mission because of bad weather, engine failures, or other reasons, or those who had made a forced landing before reaching a destination. My case, in which I was shot down over an enemy ship and returned, is very rare. . . .

War is part of the history of human interaction. The reason for my being here is to fill the void in my own memory, not to condemn or judge the past at a national level. I do think we should make every effort to judge the war in a fair manner. I would like to preserve the historical record related to the war in memory of those who died. I am planning to visit the families of the dead and explain the condition to them. As a result of our plane’s having been shot down, both of the other men in my crew that day are dead. Warrant Officer Yoshida’s older brother is living in Kyushu, as is the family of Mr. Koyama, the pilot of the airplane. I plan to visit them to explain what happened, based upon the confirmation of the past using your official historical records.