The Washington Naval Accords of 1922, an interlinked series of eight treaties, addressed the drivers of geopolitical competition in East Asia by constraining the militaries of the major powers, rupturing the Anglo-Japanese alliance, opening China to trade, and ending Japanese control of Shandong, China. The administration of President Warren G. Harding believed the Washington Treaties would prevent war, reduce the cost of the Navy, and have more public appeal than continued naval building programs. France’s government summarized the treaties’ purpose: “The pretended disarmament of the accords of Washington is not a disarmament of peace, but a disarmament of war.” The powers negotiated, France believed, “with the idea of being able, if the occasion arises, to make war in the best conditions and cheaper.”1

The treaties limited warship types, tonnage, and armaments as well as expansion of shore facilities. In particular, the numbers of battleships, cruisers, and aircraft carriers for each country were subject to numerical limits; submarines and destroyers were instead limited by magnitude to 10,000-ton displacements. But the restrictions came alongside treaties that gave each major power something: Britain, the largest fleet affordably; the United States, an end to the Anglo-Japanese defense agreement and naval parity with Britain; and Japan, international stature and prevention of new defenses on U.S. and British holdings in Asia.

By setting fixed ratios for the size and numbers of capital ships, the Washington Naval Accords advantaged innovation in new forms of maritime power. The navies of the United States and Japan accelerated in creative ways; Britain’s Royal Navy did not. The respective successes and failures provide insight into why and how militaries innovate—and how to think about the challenges of innovation in the present.

Britain. To the extent the accords were deleterious to Britain, it is mostly because the Royal Navy innovated less urgently and interestingly than the United States or Japan.

After World War I, the United Kingdom still had the world’s paramount naval force, but the United States and Japan were rising fast; postwar Britain was unable to match their naval spending and conscious of its evaporating hegemony. Allied with Japan since 1902, the British were more concerned with U.S. ambitions. Britain’s military in 1921 confronted “prolonged political hostility” domestically because of World War I casualties, humiliating failures at Gallipoli and Jutland, and popular disarmament campaigns.2

The restraints in the Washington Naval Treaties had a disproportionate effect on the Royal Navy. Fleet reductions in the treaties were greatest for Britain, which had to scrap 20 extant capital ships. Hulls already laid for Nelson-class ships had to be redesigned for smaller displacements to remain within Britain’s apportionment. (These would come to be referred to as “cherry tree classes” because they were “chopped down” by Washington). In constraining dreadnought battleships, the Washington Naval Treaties checked Britain’s strongest suit.

The British government accepted the 1:1 ratio of maritime power with the United States and conceded its alliance with Japan because it saw no way to fund the alternative. U.S. naval planners thought the Washington Naval Accords left the Royal Navy superior in fighting strength, but London disagreed. Even decades later, an eminent British historian described the treaties as “one of the major catastrophes of English history.”3

Britain expended most of its operational and doctrinal effort repairing failures of fleet operations at Jutland, increasing independent maneuvering and prioritizing contact with the enemy. Historian David MacGregor concludes: “Surface combat was the Navy’s own idea of its reason for existence, and consequently received the highest priority throughout the interwar period.”4

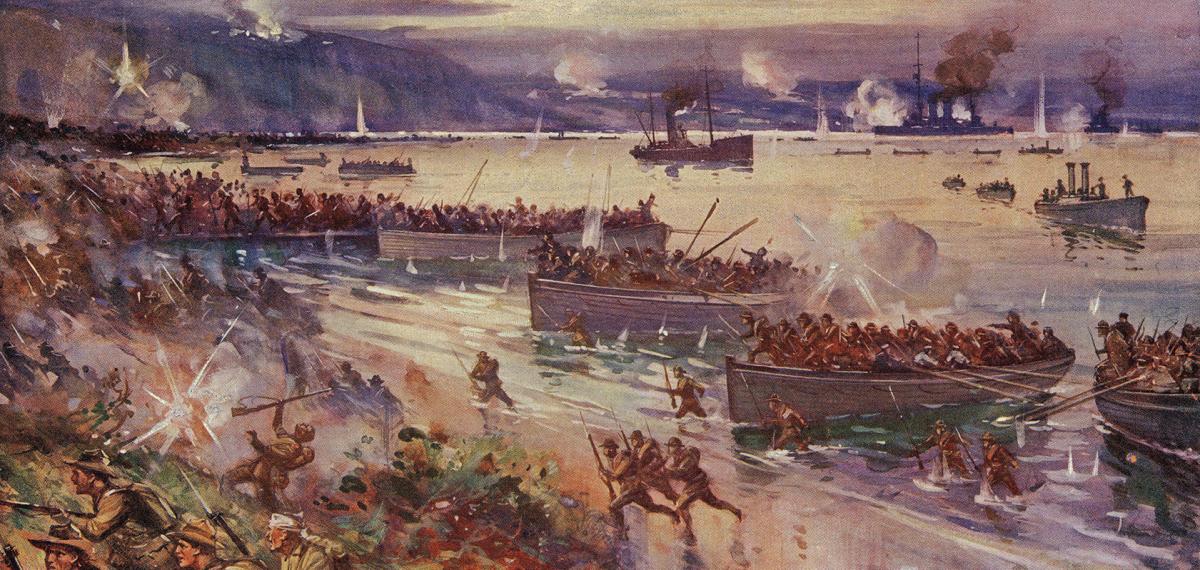

The failure at Gallipoli, too, was studied obsessively by the British military establishment. But perhaps because of its humiliation, its studies uniformly concluded that the invention of the machine gun, modern artillery, and aircraft made amphibious assaults impossible. As a result, the army and navy developed neither landing craft nor procedures for naval gunfire or air support

of a landing force.5

Britain’s services remained intensely parochial, suffering from a “debilitating complacency” about amphibious (and antisubmarine) warfare.6 As late as 1938, the Royal Navy insisted, “The Admiralty cannot visualize any particular combined operation taking place and are not therefore prepared to devote any considerable sum of money” to studying it.7 Christopher Bell captures the culture exactly: “Naval decision-makers never wavered in their conviction that sea power had always been, and should ever remain, the preeminent weapon in Britain’s arsenal, and they instinctively accepted the idea of a ‘British way’ in warfare.”8 Nor did the British establishment appreciate the “anti-intellectual aspects of such a cohesive culture.”9 As a result, when faced with the most demanding reconsideration of the three naval powers, Britain innovated the least.

In his relentless history of the corrosion of British naval power from the Napoleonic Wars to World War I, The Rules of the Game, Andrew Gordon concludes that agile adapters win wars, writing: “If doctrine is not explicitly taught, vested interests will probably ensure that wrong doctrine is ambiently learnt.”10 Britain’s record of tepid innovation in the 1921–35 treaty period of naval armament constraints suggests Gordon’s criticism remained trenchant long after his period of study.

The United States. The least economically constrained treaty party in the 1920s was the United States, its manufacturing output larger than that of the United Kingdom, Germany, France, the Soviet Union, Italy, and Japan combined.11 Despite how events are commonly presented today, U.S. funding for defense was not wholly deficient in the interwar period—not by comparison with Britain and Japan at the time, nor by the historical U.S. standard. As John Braeman argues, “Perhaps at no time in its history—before or since—has the United States been more secure.”12 But even before the Great Depression, commitment had waned to seeing through the naval expansion begun in 1916.13

And threats were mounting, with Japan openly acknowledged as the pacing threat. Over U.S. objections, the World War I settlement gave to Japan Germany’s colonial possessions in the Pacific and established the prohibition against fortifications. Given Pacific distances, this was a strong advantage for Japan over Britain and the United States.14 U.S. war plans of the interwar years never solved the problem that Philippine harbors were both indispensable to wartime operations against Japan and indefensible.15 But as Williamson Murray concludes, the eventual U.S. success “rested on serious intellectual effort that came to grips with intractable problems.”16

Many changes in military capabilities that would become revolutionary were pioneered in World War I—combined-arms tactics, submarine warfare, strategic bombing, carrier warfare—but interwar experimentation drove operational concepts that were essential to their effective use.17 In some cases, exercises even drove the technology, as with a 1921 S-boat experiment that revealed incapacities that were not remediable until 1939. The period of the Washington Naval Accords saw ships transition from coal to oil to increase speed and range; introduction of electrical power systems, radio, radar, and radio-controlled torpedoes; and improved elevation of turreted guns increasing firepower. Tonnage limits also spurred submarine designs to maximize cruising distance and torpedo power and encouraged improvements in ship design by requiring substitution of plastic and aluminum for heavier metals.18

The Washington Naval Accords required efficiency of the U.S. Navy. The 394 destroyers built at the end of World War I precluded construction of more for 12 years, so the Navy channeled modernization efforts into light cruisers.19 The treaty restrictions, coupled with the demands of security in East Asia, created a general atmosphere of innovation in the service.20 Even so, military historians—and the military leaders of the time—derided the unwillingness of the Presidents and Congress to fund the military more fulsomely, especially before the Depression.

When the Naval Accords went into effect, the Navy was still in thrall to Mahan’s grand fleet actions; that changed dramatically across the accords’ duration.21 War plans evolved through the 1920s and 1930s from incompatible Army and Navy propositions to encompass combined-arms operations, Marine Corps doctrinal development of amphibious operations, island-hopping (since bases could not be reliably held), and acknowledgment of the need for unrestricted submarine warfare at least in “strategical areas.”22

Professional development and wargaming explored naval aviation as an independent strike force, and the operational navy experimented with implementing aircraft carrier concepts that increased the pace of aircraft operations, use of arresting cables, development of crash barriers, and optimization of flight deck operations.23 The experimentation was so effective that, in 1934, Rear Admiral Ernest King, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, claimed that U.S. naval aviation had “reached a degree of efficiency not equaled by any other power.”24

Admiral King proved incorrect in that assessment. The Imperial Japanese Navy innovated even more spectacularly in many ways.

Japan. The Washington Accords affected Japan’s threat perceptions, national strategy, technology, military buildup, and operational concepts tested by exercises—as well as drove radicalization of the officer corps, which saw purges of accommodationist officers and even assassinations. For no other country were the effects as significant.

Japan became a great power via “catch-up” industrialization through technology-transfer agreements made with Western firms and imitation of foreign products; half of those foreign firms were American.25 Britain and France supplied Japan with technology, advisors, and ships and celebrated their effectiveness during the Sino-Japanese War.26

Imperial Japanese Navy leaders were dedicated Mahanians; their 1918 Imperial National Defense Policy planned to take the Philippines in the initial phase of any war, then engage the United States in a decisive battle in the western Pacific.27 But they had assessed that a 70 percent ratio “assured Japan ‘a strength insufficient to attack and adequate for defense,’ and imperative as a deterrent to the United States.”28

From its inception, attitudes about the Washington Accords were deeply divided in Japan. Japan’s objective in the negotiations was to minimize differences with Britain and especially the United States.29 Whereas Navy Minister (and active-duty Admiral) Kato Tomosaburo supported arms limits because of U.S. economic superiority, Vice Admiral Kato Kanji argued that superiority required Japan’s peacetime force to deter or conclude the war before U.S. advantages could be brought to bear. The “battle of the two Katos” resulted in acceptance of the Washington Naval Accords at the cost of military embitterment. On the day Japan accepted the treaty, Vice Admiral Kanji “was seen shouting, with tears in his eyes, ‘As far as I am concerned, war with America starts now.’”30

While restraints on a militarized Japan may well have been what Ernest Andrade Jr. called “a diplomatic achievement of major importance,” they were also the catalyst to an amazing series of innovations unhindered by restraints that might have remained in place without the Washington Accords.31

By 1923, because of the treaties, the Japanese government revised its national defense policy to accept that war with the United States was inevitable, and plans extended the radius of action to include offensive mid-Pacific intercept operations. During its time as a party to the Washington Naval Accords, Japan developed large high-speed submarines to implement the strategy and mastered night attacks by surface vessels; matured joint doctrine for amphibious operations and pioneered the first amphibious assault ships; and designed and built Nakajima Type 97 attack bombers, Aichi Type 99 dive bombers, the Zero fighter plane, rockets, dive-bombs, and advanced aerial torpedoes.32 New tactics such as the employment of the carrier task force in a box formation also allowed the massing of naval aviation for greater operational effects.33

Japan respected the Washington system until 1931 and formally withdrew in 1935, setting off “the race to Pearl Harbor.”34 Williamson Murray writes, “The record of the U.S. military is far and away the most impressive of any nation in the 1920s and 1930s.”35 This undervalues the remarkable innovations Japan achieved with even more tightly constrained budgets.

A Victory of Imagination

Successful innovation requires a demanding and specific problem; organizational openness to new thinking; an ability to test and compare alternative solutions; money to develop new technology and build equipment; and leaders dedicated to forcing advantageous change into routine practice.

Such reengineering does not mean solutions will necessarily be optimal—or even correct—but without them, innovation is stifled.36 And innovation is not always the solution; as businessman Bill Turpin cautions, sometimes there will not be a silver bullet, and a whole lot of lead bullet will have to suffice.37 But faced with common constraints and a common inability to spend their way out of their problems, the militaries of the United Kingdom, the United States, and Japan spent 13 years grappling with how to innovate their way to success in a war over East Asia.

Charles O’Reilly argues that successful organizations struggle to innovate because innovation requires challenging the culture that made for success. Successful organizations, he says, “actively try to preserve their core competencies.”38 All three great power navies were successful organizations in 1921, but the Washington Naval Accords disrupted the core competencies of all three navies. Each understood its enemies were innovating whether or not it was.

Two of the three navies found paths to success, and then those two navies fought each other. At the end of the war, both of the two Katos from Japan’s delegation to the Washington Naval Accords were proved right: U.S. economic superiority meant Japan gained advantage by accepting arms control limits on its forces, and U.S. economic superiority became decisive because the war was not quickly won by Japan.

Britain’s failure was, ultimately, one of imagination; it could not imagine itself as other than what it had always been, even as Washington and especially Tokyo imagined new ways to fight. The U.S. military innovated before the war just enough to hold its own until those economic advantages could be brought to bear. Today, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps should ask themselves whether the current force more closely approximates the one that burst into being during the Washington Naval Accords years—or the Royal Navy that remained so beholden to its past successes and ashamed of its failures that it stifled the creativity and experimentation needed to face the looming challenges. It may be propitious that (as Andrew Gordon notes) then–Vice Admiral John Richardson encouraged the Naval Institute Press to publish the 2013 edition of The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command.

1. Alexandre Bracke, quoted in Joel Blatt, “The Parity That Meant Superiority: French Naval Policy towards Italy at the Washington Conference, 1921–22, and Interwar French Foreign Policy,” French Historical Studies 12, no. 2 (Autumn 1981): 244.

2. Brian Bond, British Military Policy Between the Two World Wars (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1980), 35.

3. Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Faber and Faber, 2011), 272; John Braeman, “Power and Diplomacy: The 1920s Reappraised,” The Review of Politics 44, no. 3 (July 1982): 355.

4. David MacGregor, “The Use, Misuse, and Non-Use of History: The Royal Navy and the Operational Lessons of the First World War,” The Journal of Military History 56, no. 4 (October 1992): 613.

5. MacGregor, “Use, Misuse, and Non-Use of History,” 607; Williamson Murray, Transformation and Innovation: The Lessons of the 1920s and 1930s (Institute for Defense Analysis, December 2002), 4, 10 (footnote 24)—though Murray is not entirely fair to the British.

6. The excellent term is David MacGregor’s.

7. MacGregor, “Use, Misuse, and Non-Use of History,” 614.

8. Christopher M. Bell, “Neither Corbett nor Mahan: British Naval Strategy and War Planning,” The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy Between the Wars, Christopher M. Bell, ed. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), 127.

9. Brett Steele, Military Reengineering between the World Wars (The RAND Corporation, 2005), 12

10. Andrew Gordon, The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2013), 580.

11. Braeman, “Power and Diplomacy,” 345.

12. Braeman, 369.

13. Louis Morton, “Interservice Co-operation and Political-Military Collaboration,” Total War and Cold War: Problems in Civilian Control of the Military, Harry L. Coles, ed. (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1962), 142.

14. Dudley W. Knox, The Eclipse of American Sea Power (New York: American Army & Navy Journal Inc., 1922), 135–36.

15. Louis Morton, “War Plan Orange: Evolution of a Strategy,” World Politics 11, no. 2 (January 1959): 228, 237, 244.

16. Murray, Transformation and Innovation, 21.

17. Murray, 4.

18. Ernest Andrade Jr., “Submarine Policy in the United States Navy, 1914–1941,” Military Affairs 35 (April 1971): 50–56.

19. William R. Braisted, The United States Navy in the Pacific, 1909–1922 (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1971), 687–88.

20. Thomas C. Hone, “The Effectiveness of the ‘Washington Treaty’ Navy,” Naval War College Review 32, no. 6 (November–December 1979): 58.

21. J. E. Talbott, “Weapons Development, War Planning and Policy: The US Navy and the Submarine, 1917–1941,” Naval War College Review 37, no. 3 (May–June 1984): 60; Stephen Peter Rosen, Winning the Next War: Innovation and the Modern Military (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991), 142.

22. Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War: A History of United States Military Strategy and Policy (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 249–53; Lester H. Brune, The Origins of American National Security Policy: Sea Power, Air Power and Foreign Policy 1900–1941 (Manhattan, KS, 1981), 45–55, 68–76; Louis Morton, “War Plan Orange,” 227, 237, 249.

23. Rosen, Winning the Next War, 40–43.

24. Quoted in Thaddeus Tuleja, Statesmen and Admirals, 106–7.

25. Kozo Yamamura, “Japan’s Deus Ex Machina: Western Technology in the 1920s,” The Journal of Japanese Studies 12, no. 1 (Winter 1986): 71.

26. Cathryn Morette, “Technological Diffusion in Early-Meiji Naval Development, 1880–1895,” Emory Endeavors 2013, 205.

27. Sadao Asada, “The Revolt against the Washington Treaty: The Imperial Japanese Navy and Naval Limitation, 1921–1927,” Naval War College Review 46, no. 3 (Summer 1993): 83.

27. Asada, “Revolt against the Washington Treaty,” 84.

29. Tadashi Kuramatsu, “Britain, Japan and Inter-War Naval Limitation, 1921–1936, From Allies to Antagonists,” in The Military Dimension, vol. 3, Ian Gow and Yoichi Hirama, eds., 128.

30. Asada, “Revolt against the Washington Treaty,” 86–88.

31. Ernest Andrade Jr., “The United States Navy and the Washington Conference,” Historian 31 (May 1969): 361–62.

32. Allan R. Millet, “Assault from the Sea: The Development of Amphibious Warfare Between the Wars,” in Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millet eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 81.

33. Lisle A. Rose, Power at Sea, vol. 1 (Columbia. MO: University of Missouri Press, 2007), 141–42.

34. Stephen E. Pelz, Race to Pearl Harbor: The Failure of the Second London Conference and the Onset of World War II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1974).

35. Murray, Transformation and Innovation, 1.

36. Steele, Military Reengineering.

37. Ben Horowitz, The Hard Thing About Hard Things (New York: Harper Business, 2014), 88.

38. Charles O’Reilly, Winning Through Innovation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 3–13.