The U.S. Naval Institute published its very first book in 1899—Log of the U.S. Gunboat Gloucester. In the typical style of the day, the title page includes the words “Commanded by Lt.-Commander Richard Wainwright and The Official Reports of the Principal Events of Her Cruise During the Late War with Spain.” That cruise included participating in the U.S. blockade of the Spanish fleet, which had sought refuge in the Cuban port of Santiago, and then engaging elements of the enemy fleet, when its commander, Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, attempted the breakout that led to the overwhelming victory of the Americans over the Spanish in what has become known as the Battle of Santiago.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

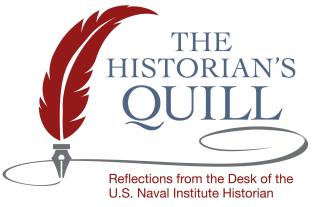

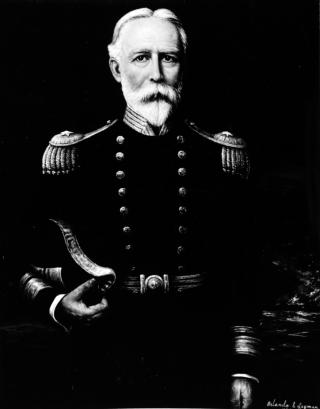

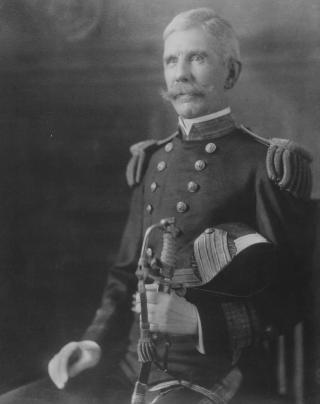

Included in the front matter of the book is a photograph of Wainwright, a handsome man dressed in the high-collar (“choker”) blue uniform jacket of the day and sporting a rather abundant mustache that would not pass muster today.

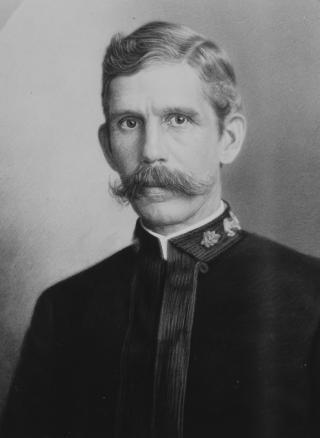

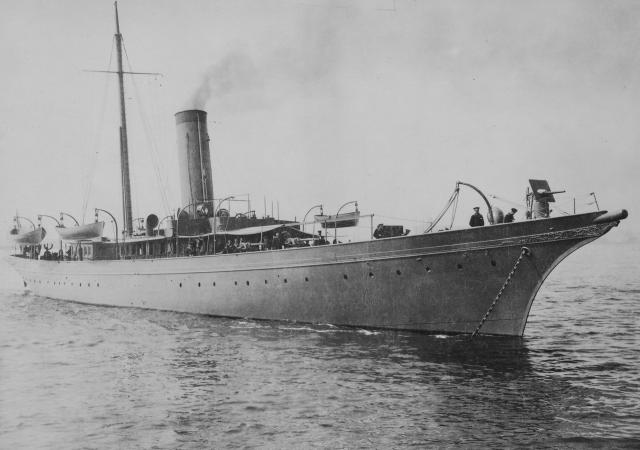

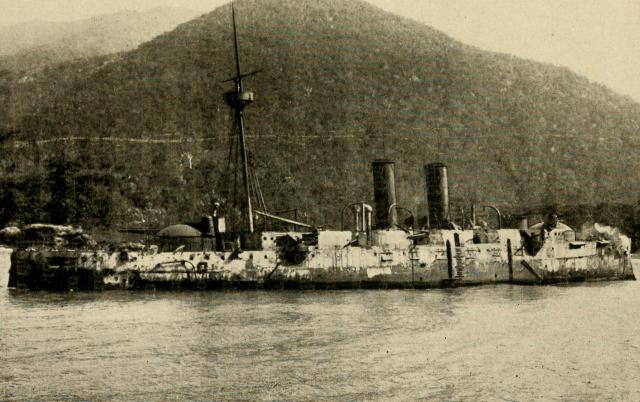

Also included is a New York Yacht Club photograph of the Corsair, a yacht owned by J. P. Morgan that was converted to the U.S. gunboat Gloucester and brought into service when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898.

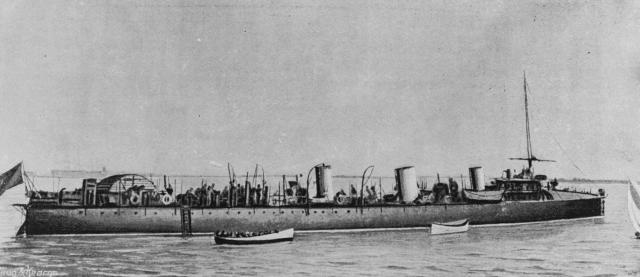

Beneath the photo are some basic statistics, such as her displacement at 786 tons, length overall 241 feet, draft of 15 feet, and coal capacity of 93 tons. A second photo shows the converted vessel and lists her armament as:

·Four 6-pounder Hotchkiss R.F.G. [rapid fire guns] two on each bow.

·Four 3-pounder Hotchkiss R.F.G. one on topgallant forecastle, one on starboard quarter, one on port quarter, and one over stern.

·Two 6-millimeter automatic rifles on movable mounts.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

The next page includes an “Extract from the Report of Rear-Admiral Sampson, Commander in Chief, on the Battle of July 3, 1898,” and the next 126 pages reproduce the official log, watch by watch, day by day, from 16 May to 4 September 1898. The very first entry is:

Quintard Iron Works, New York, Monday, May 16, 1898. 11 A.M. to midnight:

At 11:00 o'clock anti Meridian the ship was formally put in Commission. Officers present: Lieutenant-Commander Richard Wainwright, Captain; Lieutenant Harry P. Huse, Executive; Ensign John T Edson; Assistant Surgeon J. F. Bransford; Assistant Paymaster Alexander Brown; Passed Assistant Engineer George W. McElroy. Assistant Engineer Andre M. Proctor reported on board for duty. Workmen from Quintard Iron Works on board engaged in installing gun-mounts, caulking, painting, fitting battle screens for deck-houses, and generally overhauling interior of ship.

HARRY P. HUSE, Lieutenant, U.S.N., Executive and Navigator.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

The log entries are succinct and colorless as one might expect, with many notes on the current weather, course and speed changes, navigational points, tides and currents, lookout sightings, periodic coal replenishments, and various administrative matters, such as personnel transfers, judicial punishments, and crew injuries. Despite their brevity and paucity of adjectives, the entries nonetheless present a “you are there” experience that is both edifying and entertaining.

Wednesday, 8 June 1898 is the first entry showing the ship on blockade duty off Santiago, Cuba, having reported the Gloucester’s arrival during the forenoon watch to Rear Admiral William T. Sampson, commander of the North Atlantic Squadron. After suffering the somewhat mundane duty of delivering mail to the various ships on blockade duty, the gunboat received orders from the flagship that same afternoon to “keep close by for orders.” The 8 P.M. to midnight entry reads, “Cloudy first part, clearing after ten, with bright moonlight. Prepared to land a Cuban general, with staff of six officers, at Acerradero.” The next entry (Midnight to 4 A. M.) reports clear weather, then:

At 12.10 sent away armed boat’s crew to land Cuban party at Acerradero three miles distant bearing north. Then ran off shore and at two o'clock ran in and picked up boat which had carried out her mission. Steamed east to our position in the blockade passing through outer line unchallenged.

GEORGE H. NORMAN, JR.

From there, the entries become rather repetitive, reflecting the tediousness of blockade duty, with the phrase “lying off Morro Castle” appearing frequently, with little else other than the weather recorded.

In an August 1928 Proceedings article marking the 30th anniversary of the battle, Commander L.J. Gulliver recorded:

Although the blockade of the Spanish ships in Santiago harbor by Admiral Sampson’s fleet had been in effect only a little more than a month, the officers and crews of our ships had begun to tire of the inaction. There had been plenty of excitement when the bottling-up process started near the end of May, and there were at first numerous volunteer lookouts aloft day and night. Expectancy was high that the Spanish fleet would come out and fight. No one wanted to risk being below and asleep when the Spaniards made the dash. But as the days wore on and Santiago harbor continued as quiet as the grave, the blockade became dull work. Lookouts had to be jacked up. The Navy’s itch for a fight seemed less likely each day ever to be satisfied.

At last, on Sunday, 3 July, the tedium yielded. In his memoir My Fifty Years in the Navy, republished in 1984 as one of the Naval Institute Press’ Classics of Naval Literature, Admiral Sampson recalled:

It was Sunday morning, and a beautiful, clear day. I was in my cabin and had just buckled on my sword and taken up my cap to go on deck, for the first call for inspection had sounded, when suddenly the brassy clang of the alarm gongs echoed through the ship, and the orderly burst through the cabin door, exclaiming, “The Spanish fleet Sir! It's coming out!”. . . . I hurried on deck, thinking it must be a false alarm. . . . Just then I saw clearly enough the military top, and then the bow and smokestack of a man-of-war sliding rapidly past the second point in the harbor, and as she disappeared behind the Morro [Castle], the leading ship rushed out from the entrance with a speed that seemed inspired by the assurance of victory, firing her guns as she came.

(Courtesy of the Author)

On the Gloucester, the log recorded:

Clear and warm; at 9.30 went to quarters for inspection. Captain began inspection of ship and crew. At 9.43, Mr. Proctor having the deck, Spanish fleet came out of the harbor, Gloucester being then about 3000 yards southeast of Morro. Went to general quarters and Executive took the deck. Opened fire at 3500 yards range from after guns and forward starboard guns as they were brought to bear. Started fire room blowers and turned to starboard, decreasing range to 3000 yards. Four Spanish cruisers came out in column and stood to westward. Slowed down to wait for torpedo-boat destroyers, at the same time keeping up fire on cruisers from port battery. Iowa, Indiana, Oregon, Texas, and Brooklyn engaged Cristobol Colon, Oquendo, Maria Teresa, and Viscaya, all standing to westward. Forts on shore kept up slow fire during action. When larger vessels were well clear and the rear one about 1500 yards to westward of Morro, destroyers Pluton and Furor came out and followed in their wake. Opened rapid-fire on them from starboard battery at 2500 yards range and ran engines at full speed, heading course about W N W. Indiana signaled “gunboats will advance.”

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

Although there were two gunboats participating in the blockade, the Ericsson had left her position that morning to accompany the armored cruiser New York for a meeting at Siboney, east of Santiago, with Army Major General William Shafter. That left only the Gloucester to respond to the order to advance.

In his formal report written three days later and reprinted in the book after the log, the Gloucester’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Wainwright, reported:

It was the plain duty of the Gloucester to look after the destroyers, and she was held back, gaining steam, until they appeared at the entrance. The Indiana poured in a hot fire from all her secondary battery upon the destroyers, but captain Taylor's signal, “Gunboats close in,” gave security that we would not be fired on by our own ships. Until the leading destroyer was injured, our course was converging necessarily; but as soon as she slackened her speed, we headed directly for both vessels, firing both port and starboard batteries as the occasion offered.

Commander Gulliver elaborated:

Before the Spanish destroyers appeared in sight, the Gloucester opened fire with her 3-pounders and 6-pounders on the Spanish flagship and headed in towards the enemy column, but very soon Captain Wainwright decided that his particular business that day was the Spanish destroyers, and slowing his engines, he directed that a full head of steam be “bottled up” preparatory for the running dash that he meant to make at them, following the good old Navy primitive tactics, “Let’s get at them quick.” Immediately [when] the Pluton and Furor showed themselves at the harbor mouth, Captain Wainwright rang full speed ahead, and porting his helm, he drove down upon them, his forward guns concentrating on the leading Pluton and the after 3-pounders on the Furor. The Gloucester was “traveling”— a good seventeen knots—a lot of speed in ’98. She was making a brave sight, too, with a bone in her teeth, and a constant sheet of flame, white-red in the Cuban sun, bursting from her spar deck guns.

Five of the ship’s officers—Lieutenants Harry Huse, Thomas Wood, and George Norman, Ensign John T. Edson, and Chief Engineer George W. McElroy—also submitted after-action reports, all of which are included in full in the book after Captain Wainwright’s. Huse, who was the officer of the deck throughout the engagement, wrote that “The fire from both sides was vigorous, but while many [enemy] shots struck the water close alongside or went whistling over our heads, we were not hit once during the whole engagement.”

In his after-action report, Lieutenant Wood, who was in charge of the after division, confirmed the poor marksmanship of the Spanish gunners: “The destroyers speeding westward replied to our fire, but with deliberation and great inaccuracy.” However, he subsequently noted that “the machine gun fire of the Furor was trained on us, and I noted the shots striking the water and gradually reaching towards us as the range decreased. The fire suddenly stopped before the bullets actually found us, owing probably to the disconcerting effect of our fire upon that vessel.”

Huse confirmed this by reporting that “the monotonous reports of an automatic gun could be heard after the 2500-yard range was passed and the zone of fire could be distinctly traced by a line of splashes describing accurately the length of the ship and gradually approaching it. But at a distance variously estimated from ten to fifty yards, the automatic fire ceased. [The Spanish gun] was afterwards found to be a 1-pounder Maxim, and the execution aboard [our ship] would have been terrible during the few minutes that must have elapsed before the ship was sunk had the fire reached us.”

According to Ensign Edson’s report, the gunfire from the men in his division “was as good as that shown at target practice.” The log for the time before the battle confirms successful gunnery practice, although not a great deal of it. Edson continued, “it was during this fire that the boilers of the Pluton were pierced.”

Huse concurred with Edson’s gunnery assessment, recalling that “the service of our guns was excellent, and at a range of twelve hundred yards, the two 6-millimetre automatic Colt rifles opened up on the enemy.” Wood reported, “At 600 yards I observed the leading destroyer (Pluton) was heading towards and close to shore about two miles to the westward of Morro. Smoke and steam were rising from her, her fire was almost stopped, and she was quite a distance in.” Huse observed, “The Pluton had now (about 10.15) slackened her speed, showing evident signs of distress, and our fire was concentrated on the Furor.”

Both Spanish ships had taken a beating. The Pluton continued to close the beach, and upon grounding on the rocks four miles west of Morro, exploded. Seeing that the Furor “was pointing off shore and in our direction,” Lieutenant Wood thought “she was about to close with us. She continued to turn, however, completing her circle to port at decreasing speed.” Soon the Spaniards waved a white rag in surrender, and the Gloucester ceased firing.

As recorded in the book, Captain Wainwright sent boarding parties to Furor to see if her fires could be extinguished and the vessel preserved for capture. Lieutenant Wood and five other men arrived to find the destroyer in bad shape:

On reaching the Furor a scene of horror and wreck confronted us; the ship was riddled by three- and six-pound shells, although I observed no damage by large projectiles; she was on fire below from stem to stern, and on her spar deck were the dead and horribly mangled bodies of some twenty of her crew and officers. One of her boats was at the davits, smashed to atoms; another I afterwards found a short distance away, stove but sustaining 2 survivors, whom I rescued. In the meantime, another of the Gloucester’s boats arrived and boarded the wreck in charge of Lieutenant Norman, and between us we rescued some 10 or 12 of the crew which remained on board. Finding it impossible to save the ship and fearing damage to our own men from explosions, I directed our two crews with the surviving members of the Furor’s crew, to instantly abandon the ship and return to the Gloucester…An explosion occurred almost immediately after we abandoned the vessel, and her stern commenced slowly to settle for 10 minutes when her bow began to rise. When the ship was nearly up and down she sank about 200 yards from shore.

After departing the Furor, Lieutenant Norman took his party of eight in the gig to rescue the surviving crew of the flagship Infanta Maria Teresa, “who could be seen crowded upon the bows of their ship, the after part and waist being afire and burning fiercely.” Norman and the others managed to rescue 480 of the crew, ferrying them ashore while small explosions were “constantly occurring on and between her decks,” and the Spanish crewmembers warning that they feared the fires might reach the forward magazine.

Once all had been removed from the burning Spanish ship, Norman “backed my boat in on the lifeline as near to the surf as possible and sent a man ashore with orders for the Admiral [Cervera], the Fleet Captain, and the five other officers next in rank [including the admiral’s son, Lieutenant Angel Cervera], to come out to my boat, which they promptly obeyed, two of our own men dragging them one at a time along the life line through the surf to our boat’s side.”

Norman then took the Spanish officers to the Gloucester. All were soaking wet, and Admiral Cervera was clad only in an undershirt and trousers, but “throughout the long pull out,” Norman reported, “Admiral Cervera and his officers expressed much gratitude for our rescue of them and their crew.” Once on board the Gloucester, Captain Wainwright reported that “the Admiral, his officers, and men, were treated with all consideration and care possible. They were fed and clothed as far as our limited means would permit.”

(Public Domain)

For the Gloucester, the battle was over. The achievements of this diminutive but pugnacious gunboat were unquestionably significant. In this age when battleships and cruisers were the uncontested capital ships that dominated the battle fleet, there was the nagging concern that these leviathans were vulnerable to torpedoes. The Gloucester’s successful attack on the Spanish destroyers eliminated that concern and allowed the “heavies” to concentrate on their Spanish equivalents and score one of the most successful triumphs in American naval history.

In his 1928 Proceedings article, Commander Gulliver made an interesting observation regarding Captain Wainwright’s preparations for the battle:

Among the plans for converting the Gloucester to a regular gunboat was placing a fairly heavy layer of armor on her sides—good protection, no doubt, that would probably have rated her third class instead of fourth; but this project, so strongly urged, was successfully resisted by Captain Wainwright, and on his decision really rested the Gloucester’s fame in the fight that was to come. He chose to take her as she was— unprotected—but with her speed undiminished by the weight of the proposed armor. Had Captain Wainwright acted differently, the Gloucester would never have had the speed to overhaul the fleeing Spaniards. She would have been protected, but the mantle of glory would never have touched her. As it turned out she needed no protection, but she assuredly did need her speed and she had it in full measure.

When the smoke of battle had cleared, the tally was amazing. The Spanish destroyers had lost two-thirds of their crews killed in action or drowned. The Gloucester had lost not a single member of her crew. The only man wounded was Ensign Edson, who had suffered two broken ribs when he got too close to his gun during recoil. It was an amazing victory for a converted pleasure craft and the crew—mostly volunteers—who manned her.

Rear Admiral Sampson summed it well when he wrote, “the skillful handling and gallant fighting of the Gloucester excited the admiration of every one who witnessed it, and merits the commendation of the Navy Department.” And Theodore Roosevelt, when later referring to the Battle of Santiago, observed, “the most striking act was that of the Gloucester, a converted yacht, which her commander, Wainwright, pushed into the fight through a hail of projectiles, any one of which would have sunk her, in order that he might do his part in destroying the two torpedo boats, each possessing more than his own offensive power.”

The Gloucester’s impressive young captain, Lieutenant Commander Richard Wainwright, went on to a successful Navy career, retiring as a rear admiral. His father was a lieutenant colonel of Marines and grandfather had been Farragut’s flag captain in the Hartford at New Orleans and Vicksburg. Wainwright himself had been executive officer of the USS Maine when she exploded and sank in Havana Harbor, touching off the Spanish-American War.

In addition to a successful career, Wainwright served as president of the Naval Institute and was a frequent contributor to Proceedings, beginning in 1882 and concluding just before his death in 1926—including a prize essay, “Tactical Problems in Naval Warfare,” in 1895 and an Honorable Mention for “Our Naval Power” in 1898.

Upon his death, Proceedings published “In Memoriam: Richard Wainwright, 1849–1926,” which proclaimed, “Again does the Naval Institute honor itself in rendering tribute to the memory of one who was both a former president and prize essayist, and known the world over for his distinguished professional attainments and fighting qualities.”

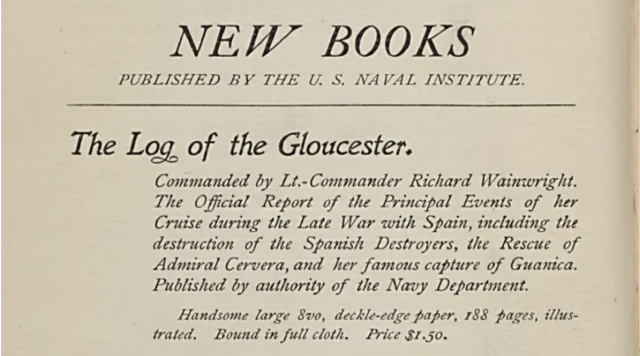

The book Log of the U.S. Gunboat Gloucester was advertised in the April 1899 issue of Proceedings as “Handsome large 8vo, deckle-edge paper, 188 pages, illustrated. Bound in full cloth. Price $1.50.” The book is no longer in print, although facsimile printings can be obtained from overseas printers, such as those found in Great Britain and in India. For some time, the Naval Institute’s only surviving copy was in tatters until Harry Harris, one of our esteemed board members, donated his copy that is in fine shape and currently displayed in the Institute’s John J. Schiff Boardroom.

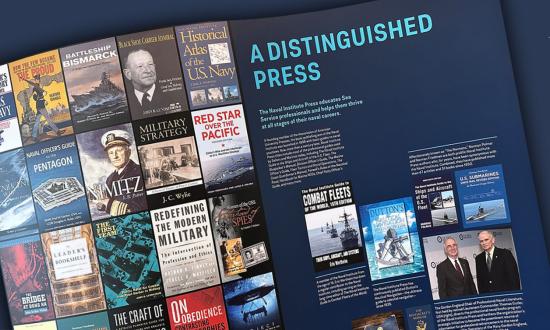

As we embrace our sesquicentennial celebration this year, we can take considerable pride in the enduring and growing legacy represented by the hundreds of titles and many thousands of books that our Naval Institute Press has published since those closing years of the century before last, including the very first: Log of the U.S. Gunboat Gloucester.