Nearly 150 years ago, 15 iconoclasts gathered in a lecture hall at the U.S. Naval Academy to commiserate over the demoralizing state of the Navy in the post–Civil War era. They ultimately wound up founding the U.S. Naval Institute, an organization that would prove to be unique, enduring, and extremely important to the naval services and the nation.

Among the many ramifications of that momentous meeting was the eventual creation of the Naval Institute Press (NIP), a relatively small-scale book publisher that has had a gratifyingly disproportionate impact, publishing countless quality tomes in many genres that edify, entertain, and, most significantly, contribute to the open forum that is at the very core of the Institute’s existence.

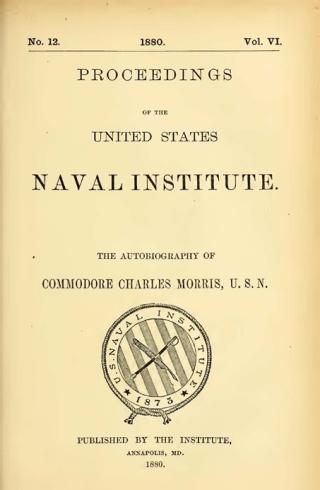

In 1898, the Naval Institute’s Board of Control made the decision that is today celebrated as the official beginning of the Naval Institute Press, but its beginnings can be traced to an earlier date. In 1880, one entire issue of Proceedings featured a lengthy piece entitled “The Autobiography of Commodore Charles Morris, USN.” While this was not a book in the traditional sense, it might as well have been. Weighing in at 108 pages, it forfeited the claims normally associated with a magazine article.

The post–Civil War Navy Department had been forced to operate on a very lean budget, so lean that it could not afford to publish the books it needed. By using the pages of Proceedings in this unorthodox manner, the Naval Institute was able to fulfill a part of its implied charter of helping the Navy accomplish its missions by providing sorely needed “books.” More followed, and it became apparent that there was a real need for a book-publishing arm of the Naval Institute.

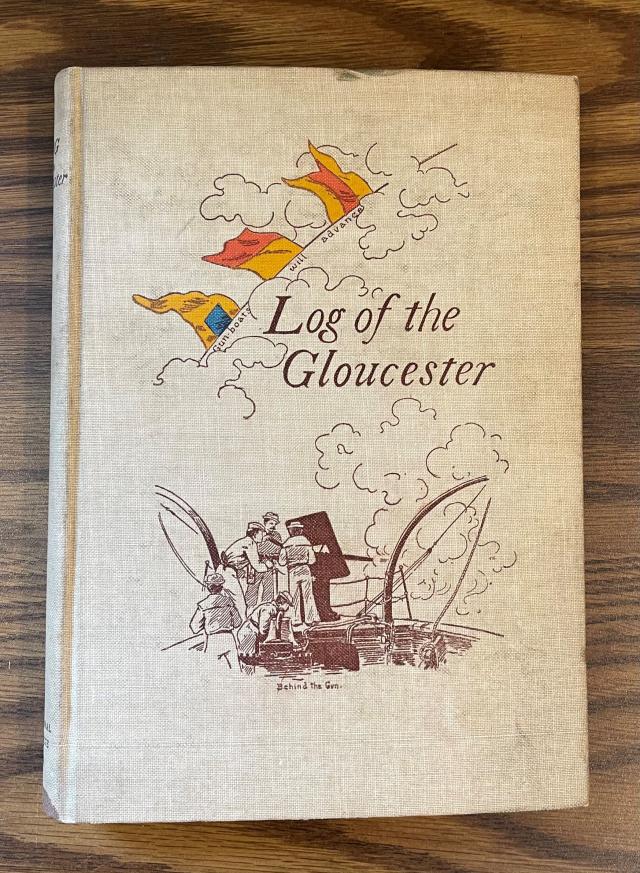

The first book not produced as a hermaphrodite version of Proceedings appeared in 1899 as Log of the U.S. Gunboat Gloucester and was advertised as “the Official Report of the Principal Events of her Cruise during the Late War with Spain, including the destruction of the Spanish Destroyers, the Rescue of Admiral Cervera, and her famous capture of Guanica.” The price for this inaugural hardcover book was $1.50.

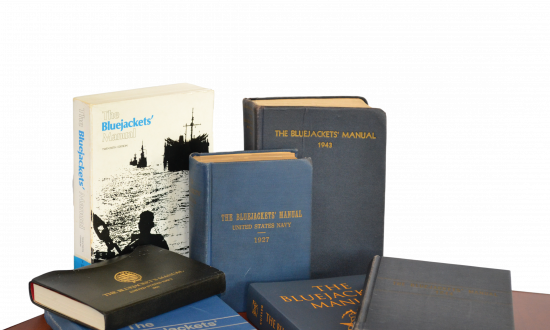

In 1902, what was to become the Naval Institute’s all-time best-seller debuted. Virtually every Sailor who has gone to sea for the last one hundred and twenty years has done so with a copy of The Bluejacket’s Manual—now in its 26th edition—in his or her seabag. Other similar books followed, such as The Petty Officer’s Drill Book, The Landing Force and Small-Arm Instructions, and Notes on Steam Engineering.

For many years, the books published by the Naval Institute Press were designed specifically as texts for use by Naval Academy midshipmen, earning the Naval Institute the unofficial but largely recognized title of “University Press of the U.S. Naval Academy.” Typical textbooks and manuals included The Oscillations of Ships, A Text-Book of Ordnance and Gunnery, and Hydromechanics.

Many of these early professional books succumbed to the vicissitudes of time and technological development, while others adapted and endured. An interesting case in point is The Manual of Wireless Telegraphy that first appeared in 1906, when the Navy was one of the early developers of electricity and electronics; it survived for decades while evolving through eight editions into Robison’s Manual of Radio Telegraphy and Telephony. Another early (1899) book, An Aid for Executive and Division Officers, which included “Watch, Quarter, and Station Bill forms on paper especially tough to withstand erasures,” eventually became The Division Officer’s Guide and is still updated and published to this day (currently in its 16th edition). These professional books were joined by many others over the years, and one would be hard-pressed to find a ship in the Navy that did not owe some of its displacement to the presence of Naval Institute Press books.

The Press also has served as a vehicle for members of the profession to formulate, debate, and implement policy. Because of the time involved in their production, books are less conducive to a dialogue than are magazines and seminars. But what they lack in timeliness, they more than recoup in depth. Often, they provide the background or the basis for a debate and therefore serve as an important component of the open forum. How Navies Fight: The U.S. Navy and Its Allies, by Frank Uhlig Jr., presented a comprehensive mosaic that put naval forces in their proper perspective by relying—as Alfred Thayer Mahan once did—on historical precedent and example.

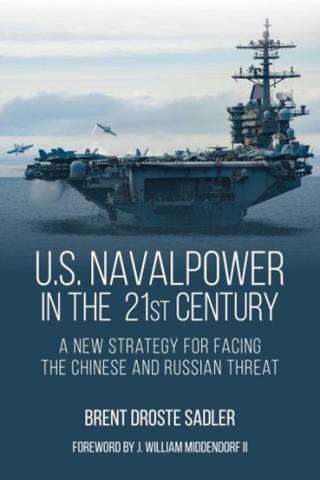

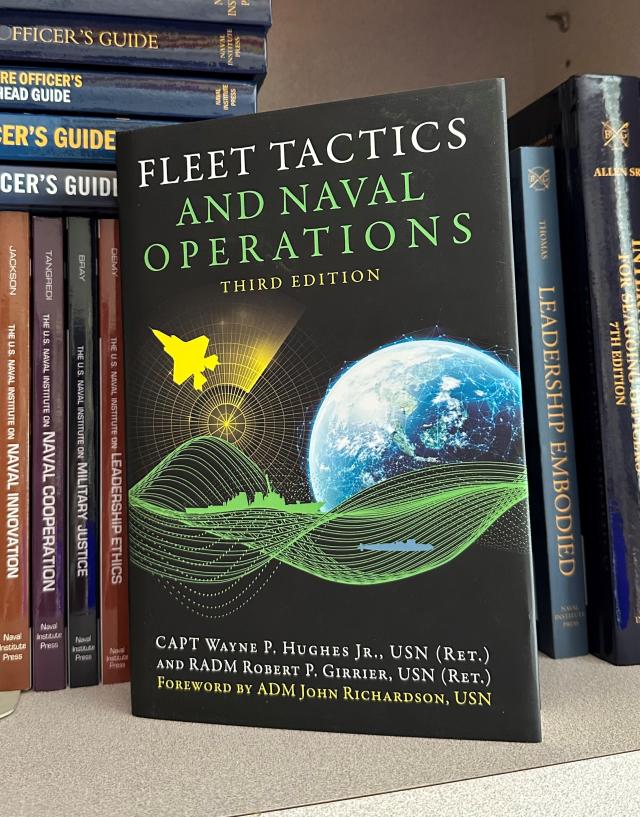

Naval strategic planning and implementation in the Cold War years was the subject of several books that appeared during that 40-plus-year “conflict.” The U.S. Navy was a key component of that ideological clash and, by describing how that service adapted to a changing strategic situation in an era characterized by revolutionary technological development and a changing national security establishment, Michael Palmer’s Origins of the Maritime Strategy: The Development of American Naval Strategy 1945–1955 provided the necessary background for further strategic development. More recently, Peter Haynes’ Toward a New Maritime Strategy: American Naval Thinking in the Post–Cold War Era and Brent Droste Sadler’s U.S. Naval Power in the 21st Century: A New Strategy for Facing the Chinese and Russian Threat have entered the forum. Captain Wayne P. Hughes Jr. served the great debate on a different level by producing his stimulating treatise Fleet Tactics: Theory and Practice in 1986, followed by two more editions.

In 1988, NIP introduced the Classics of Sea Power series, which resurrected such seminal discussions of strategic thought as Sir Julian Corbett’s Some Principles of Maritime Strategy and J. C. Wylie’s Military Strategy: A General Theory of Control. These revived works are essential reading for those who would understand the origins and development of maritime strategy and the policies that support it.

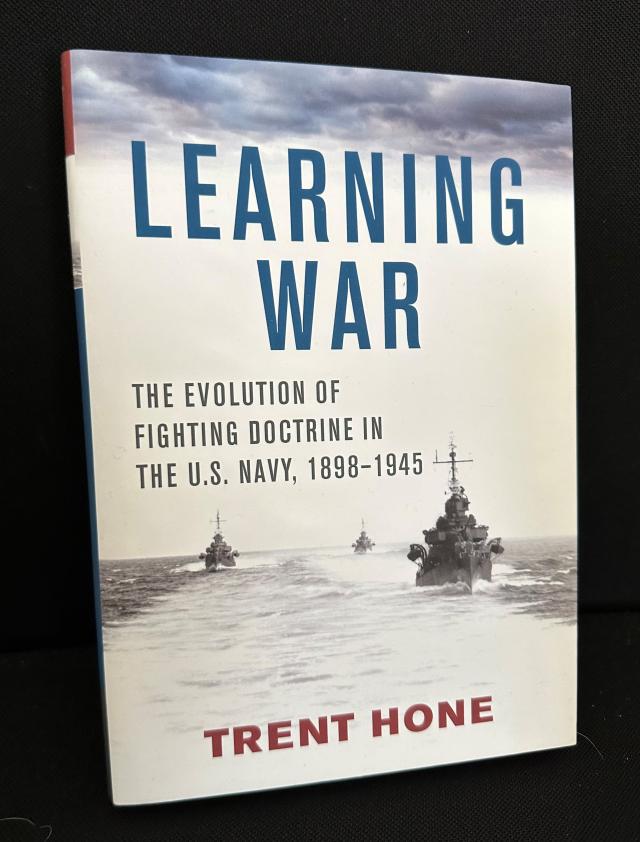

A more detailed look at a specific aspect of U.S. naval strategy can be found in Edward S. Miller’s classic War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945. Praised by former Secretary of the Navy John Lehman as “the most important book on military strategy published in years,” and described by former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral William J. Crowe Jr. as “a must read for historians, strategists, military planners, and students,” this seminal work is an illuminating blueprint of U.S. strategic planning for the Pacific campaign in World War II. More recent titles that have significantly relied on history as the blueprint for operational and strategic thinking include Red Star Rising, by Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, and Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945, by Trent Hone.

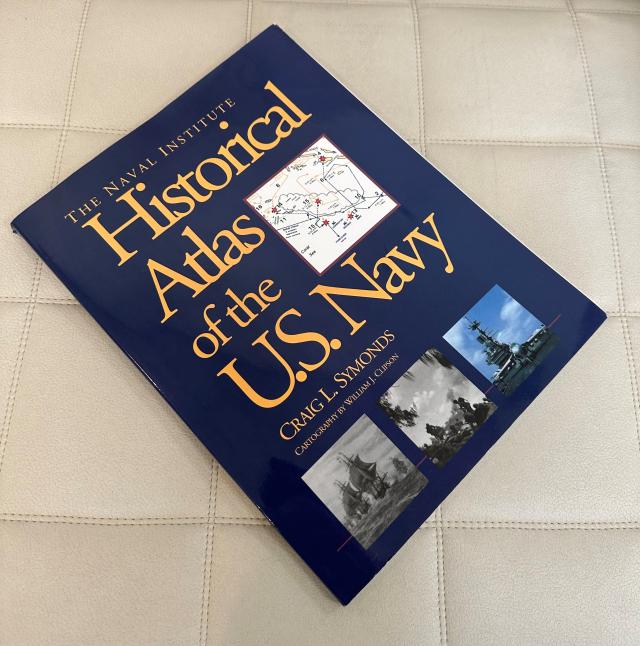

In a conversation with renowned naval historian Craig Symonds, he said that whenever he needed to refer to a book on some aspect of naval history, he found that they were almost invariably produced by the Naval Institute. One of the earliest historical works published by the Press appeared in 1920: The Yankee Mining Squadron, or Laying the North Sea Mine Barrage—a memoir written by Captain Reginald Belknap, who had supervised the operation in the last year of World War I. We Build a Navy: A History of the Origins of the U.S. Navy, from Revolutionary War Days through the War of 1812 appeared in 1929 and was the first in a series of books by Holloway H. Frost, including a seminal work on the Battle of Jutland. In 1937, Admiral William L. Rodgers’ classic Greek and Roman Naval Warfare appeared, and was followed three years later by Naval Warfare Under Oars. Symonds’ The U.S. Naval Institute Historical Atlas of the U.S. Navy is one of the best short histories of the Navy, enhanced by the excellent original cartography of William J. Clipson.

Over the ensuing decades, hundreds of significant works have been added to the pantheon of historical works published by the Naval Institute Press. Paul Stillwell’s The Golden Thirteen is a testament to the pioneering courage of a handful of African-Americans who paved the way for a better Navy and a better nation by bridging the racial divide in the officer corps. Some of the earliest biographies were written by Naval Academy Professor Charles Lee Lewis, whose two-volume biography of David Glasgow Farragut remained in print for many years as the definitive work on that subject. His final work—Admiral de Grasse and American Independence—appeared in 1945, at a time when the career of another soon-to-be biographer was just beginning. E. B. Potter’s biographies of Admirals Chester Nimitz and William Halsey were published in 1976 and 1985 respectively, and both remain in print today.

For those figures whose contributions may not lend themselves to full-length books, a number of useful “mini-biographies,” written by appropriate authorities, have appeared in essay collections edited by prominent historians. Robert W. Love Jr.’s The Chiefs of Naval Operations and Paolo Colleta’s American Secretaries of the Navy are excellent examples.

For most of its 125 years of book publishing, the Naval Institute considered fiction to be uncharted waters, but beginning in 1984, Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October, followed by Stephen Coonts’ Flight of the Intruder in 1986, enjoyed much popular attention, including feature-length films. A less celebrated but important contribution emerged in the form of a new translation of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, a fiction classic that was first published the year the Naval Institute was founded. The NIP version corrected hundreds of errors that had long been included in the standard English version and restored a lost 23 percent of the novel.

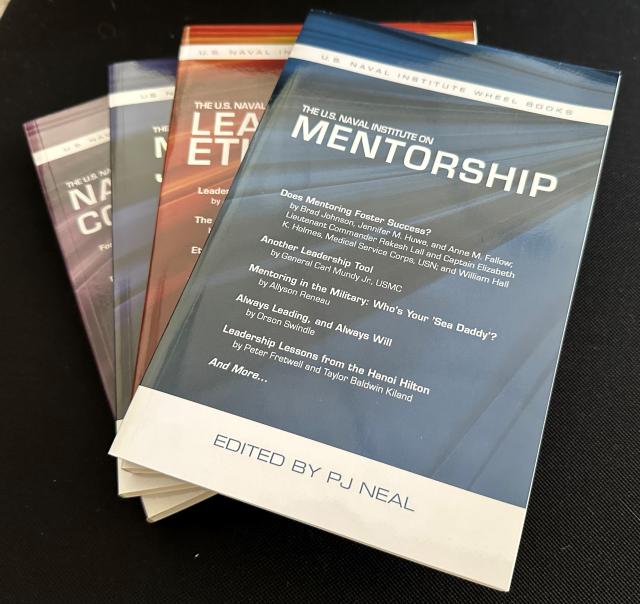

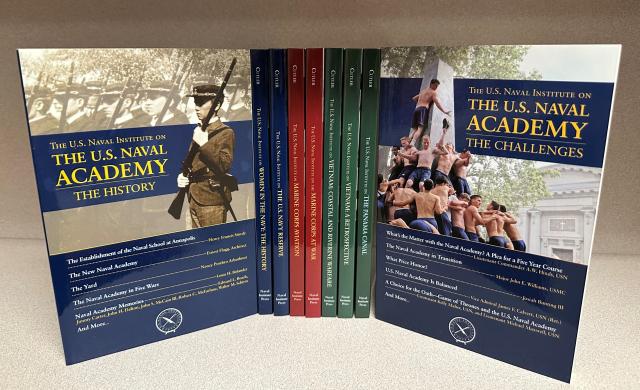

One of the many successful endeavors of the Naval Institute Press has been its use of specialized series. Today’s Navy and Marine Corps professionals rely on the Blue and Gold and Scarlet and Gold series to better carry out their duties while defending the nation. The Bluejacket Books series provides inexpensive paperback versions of many important books. The Wheel Books and Chronicles series thematically collected and annotated Proceedings and Naval History magazine articles along with excerpts from NIP books. Classics of Naval Literature resurrected many important histories, revealing memoirs, and great fiction that would have been lost to all but the most ardent library and used-bookstore miners. Bringing these titles back into print in quality bindings designed to last and enhancing them with commentaries by relevant experts, they breathed new life into such classics as Herman Wouk’s The Caine Mutiny, Thomas Buell’s biography of Raymond Spruance, The Quiet Warrior, and Edward L. Beach’s Run Silent, Run Deep.

As we embrace our sesquicentennial celebration this year, we can take considerable pride in the enduring and growing legacy represented by the hundreds of titles and many thousands of books that our Naval Institute Press has published since those closing years of the century before last. On remembering those 15 original iconoclasts who gathered in Annapolis in October 1873 to found this enduring institution, one is tempted to wonder what they might think were they able to view today this vast library among the many things they instigated. I suspect they would be enormously proud.