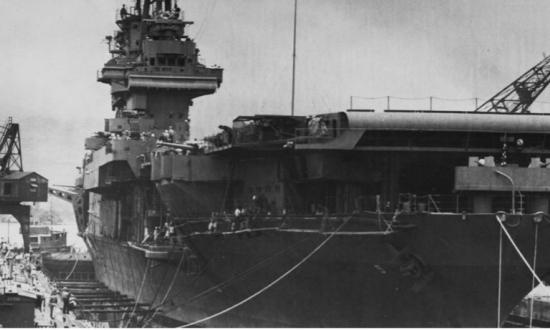

The U.S. Navy lost a flat deck. The devastating fire on board the USS Bonhomme Richard (LHD-6) in July 2020 laid bare the risk the U.S. fleet faces because of an aging and strained shipbuilding industry.

Shipbuilders currently are tasked with growing the battle fleet, decreasing the maintenance backlog, and executing a significant modernization program under the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program (SIOP). There was no excess industrial capacity that could have repaired the Bonhomme Richard in a timely manner without affecting additional shipbuilding, maintenance, and modernization efforts.1 More money would not have made a difference, as the additional dry dock and necessary skilled labor force to conduct the repairs did not exist domestically. When there is no supply, there is no price that can be paid to fill the demand.

The Navy’s inability to repair its capital ships and return them to the fleet is a clear danger to the nation’s tenuous grasp on naval superiority. Neglect of the U.S. shipbuilding industry has caused more damage to the fleet than the Soviet Union, North Korea, Iran, nonstate actors, and even the People’s Liberation Army Navy. The Navy must do better and quickly, using even nontraditional methods to increase shipbuilding capability.

Shipyard Modernization vs. Fleet Maintenance

Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael M. Gilday’s emphasis on “prioritizing investments in our critical readiness infrastructure” in his 2021 Navigation Plan, as well as the Shipyard Act, indicate the United States is turning a corner on improving its shipbuilding infrastructure.2 The Shipyard Act kick-started a $21-billion, 20-year SIOP to address the aging infrastructure of the Navy’s public shipyards. This investment aims to reduce maintenance delays caused by dated U.S. shipbuilding infrastructure. For example, from 2014 to 2019, the Navy accumulated more than 38,600 ship-days of maintenance delays—equivalent to reducing the fleet by 21 ships.3 These delays stress operational ships, leading to longer maintenance periods when those vessels enter maintenance, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

While much needed, the SIOP focuses on four public shipyards that maintain the fleet. Ensuring a robust battle fleet is essential, but the sealift fleets that resupply the battle fleet and enable joint forces to surge across oceans are currently in a poor state to sustain a high-intensity conflict. Especially worrying are the current age and readiness levels of the Ready Reserve Fleet (RRF). During a stress test in 2019, only 40.7 percent of RRF ships met mission requirements.4 With most RRF ships built in the 1960s, it is increasingly difficult to maintain them in an oceangoing state and hire personnel who can operate their Cold War–era equipment. Furthermore, the RRF’s dangerously low mission-capability rate is exacerbated by the reduction in the National Defense Reserve Fleet, which has dwindled from 274 ships in 2003 to 86 in 2021.5 While the exact readiness of U.S. sealift capability is classified, it likely constitutes a critical vulnerability in U.S. ability to move forces across the globe.

Furthermore, the slippage of the John Lewis–class replenishment oiler acquisition and continual delay of the common-hull auxiliary multimission platform indicate that even the Military Sealift Command (MSC) combat logistics fleet’s modernization efforts are taking a backseat to the battle fleet’s expansion.6 The gap between the MSC’s requirements and its inventory will only worsen in the future, as the Marine Corps intends to use a fleet of next-generation logistics ships and the light amphibious warship to resupply its expeditionary advanced bases.

The Navy’s focus on expanding and maintaining the battle fleet unfortunately creates a brittle and unbalanced force. Continued neglect of the U.S. sealift and combat logistics fleet will hinder the battle fleet’s ability to rearm and resupply, leading to fewer combatants able to operate close to conflict areas. An old and tired sealift fleet would mean the joint force cannot surge its heavier forces to aid allies in Europe and Asia even after victory at sea.

Despite the overall maritime force’s grim state of readiness, the bipartisan Shipyard Act demonstrates that there is support and will to revitalize the shipbuilding industry. But the SIOP presents a dilemma. In the current SIOP construct, the Navy is forced to choose between accelerating shipyard modernization and maintaining today’s fleet. However, if the Navy uses smaller yards and allied partners, it will be able to bridge its capability gap while rebuilding an industrial base capable of sustaining and building a robust, well-rounded fleet.

Capable Allied Shipbuilders

Long-standing partnerships with Asian nations such as Japan and South Korea could help solve the U.S. shipyard dilemma. The Navy could expand its overseas maintenance capacity and subcontract portions of its fleet maintenance to allied shipyards with a good track record of naval shipbuilding and maintenance. Larger, combat-support–oriented vessels such as oilers and sealift vessels could be contracted to allied shipbuilders to allow domestic yards to focus on facilities and process modernization, even at the cost of immediate shipbuilding and maintenance capacity.

Granted, this strategy would divert work to foreign yards, and domestic shipyards would be rightfully worried. However, the risk-reward tradeoff for such a strategy in the short-to-medium term is clear: Domestic yards would be at full capacity with modern facilities and updated processes instead of trying to produce modern vessels with century-old facilities. Until U.S. shipyard modernization is completed, U.S. allies could conduct maintenance and limited shipbuilding for fair compensation.

Japanese and South Korean (and Chinese) shipbuilders currently dominate the commercial industry and use this competitive advantage to build and maintain large fleets of advanced warships. Furthermore, the Japanese and South Korean navies consist of ships comparable to those fielded by the U.S. Navy. The Japanese Kongō, Atago, and Maya and Korean Sejong classes are essentially Arleigh Burke–class variants, while the Japanese Akizuki, Asahi, Takanami, and Murasame, and Korean Chungmugong Yi Sun-sin classes are similar in size and roles to forthcoming U.S. Constellation-class frigates. More important, firms such as Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), Japan Marine United (JMU), and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) have conducted all maintenance for their respective countries’ naval fleets since the 1980s. While a more detailed technical viability study is needed, Japanese and Korean shipbuilders likely could perform most of the maintenance on most U.S. naval vessels.7

Japanese and Korean shipbuilders can do far more than maintain and repair naval vessels. Japan builds a range of naval vessels, from the 200-ton Hayabusa-class missile boats to Izumo-class light carriers, but overall has little experience exporting arms because of constitutional limitations.8 The Korean shipbuilding industry builds a narrower variety of vessels but has a stronger record of exporting them. During the past decade, DSME exported three Type 209 Nagapasa-class submarines to the Indonesian Navy, HHI built two Jose Rizal–class frigates for the Philippine Navy, and DSME built four Tide-class fleet tankers for the Royal Navy.

At the time the tankers were ordered, building the Tide class abroad was highly controversial in the United Kingdom. Despite the political backlash, the British shipbuilding industry did not have the capacity to build Queen Elizabeth–class aircraft carriers and Tide-class tankers simultaneously. To build the two classes sequentially likely would have delayed the Royal Navy carrier strike group’s maiden deployment in 2021.9 There is no argument that timely, full domestic production of naval vessels is ideal. However, facing multiple operational and industrial pressures, the next best option for the U.S. Navy is relying on a group of close, reliable allies to supplement its naval shipbuilding.

Recommendations

The Navy can aggressively modernize domestic shipyards and recapitalize the MSC RRF fleet using domestic and foreign industrial capacity. Domestically, this will require significant planning and oversight from Navy leaders to coordinate federal infrastructure funding and balance the needs and requirements of operational commanders, state-level leaders, and industrial executives. To execute the foreign portion, the Navy will have to negotiate through the State Department with the respective partner nation’s leaders and shipbuilding firms. Here is how such a plan could be executed:

Step 1: Identify the Need

Navy leaders should commission a study on modernizing the current U.S. shipbuilding industrial base. Domestic maintenance could be limited to unique and sensitive ship classes such as aircraft carriers and submarines. This analysis should yield a list of maintenance requirements that could be shifted to improve the speed of shipyard modernization. The list could be considered the shipbuilding capability gap the Navy must fill to expedite the SIOP and deliver its desired modernized industrial base. A robust, multifaceted plan will spread requirements among multiple states, countries, organizations, and firms to create a resilient supply chain and prevent one natural, geopolitical, or economic event from hampering the Navy’s ability to maintain and build ships.

Step 2: Empower Smaller Domestic Yards

Smaller domestic shipyards not undergoing massive modernization projects should receive a portion of the maintenance backlog. These shipyards could use the revenue from these contracts not only to increase their capability in sustaining the Navy’s fleet, but also to invest in infrastructure to further modernize their facilities and processes. Navy leaders must be cognizant that occupational skills required for facility modernization will not align directly with those for shipboard maintenance. A talent-management plan needs to be formed and managed early to ensure that when yards transition from modernization to shipbuilding, the shift does not leave a glut of some skills and a shortage of others.

Specifically, there are several shipyards with sufficient dry-dock space that have previously built and maintained large naval vessels. These firms include Mare Island Dry Dock (Vallejo, California), Philly Shipyard (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), Bayonne Dry Dock (Bayonne, New Jersey) and GMD Shipyard (Brooklyn, New York). These yards provide maintenance for RRF, MSC, and Coast Guard vessels and conduct some new builds, such as Jones Act vessels and training ships for maritime colleges. There must be a strategic investment in these yards to make them capable of repairing and building naval vessels. The goal will be modern shipyards resilient to extreme climate events with sufficient capacity for midlife modernization.

Step 3: Expand the U.S. Naval Ship Repair Facility in Japan

Maintenance that cannot be absorbed by smaller domestic yards should be sent abroad. Since the Navy does not have recent experience outsourcing shipbuilding to foreign firms, significant growing pains can be expected. Using and augmenting an existing U.S. Navy vessel maintenance organization in Japan would give the Navy another tool to increase maintenance capacity while avoiding the pitfalls of standing up an entirely new organization.

A significant portion of Seventh Fleet’s intermediate maintenance is conducted in Japan at the U.S. Naval Ship Repair Facility and Japan Regional Maintenance Center (SRF-JRMC) based in Yokosuka, with a detachment in Sasebo. With a hybrid Navy, civil service, and Japanese civilian workforce, SRF-JRMC would be the perfect entity to pick up U.S. domestic yard slack while those yards modernize.

SRF-JRMC’s industrial capacity should be bolstered by a hiring campaign among existing industry personnel in Japan. Traditional barriers such as English proficiency could be addressed through education. Furthermore, the Navy could obtain a long-term lease for dry-dock facilities at Sasebo and inside Tokyo Bay. Targeted expansion and SRF-JRMC’s decades of experience in maintaining U.S. naval vessels in Japan could increase maintenance capability more quickly than contracting foreign firms to conduct maintenance on U.S. vessels.

Step 4: Use Allied Shipyards

Even domestic shipyards and a strengthened SRF-JRMC likely would not relieve all pressure on the U.S. industrial base caused by shipyard modernization, aggressive maintenance backlog reduction, and fleet expansion. The Navy should contract advanced Japanese and Korean shipbuilders to fill any maintenance gaps and build nonbattle-fleet MSC and RRF vessels.

While Naval Sea Systems Command currently does not contract ship maintenance or new construction to foreign firms, there is precedent for subcontracting complex maintenance and construction projects to foreign firms under government program management. Examples in the past decade include Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni in Japan and U.S. Army Garrison Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, South Korea. Japanese and Korean engineering firms partnered with U.S. government program managers to deliver modern, multibillion-dollar bases with the infrastructure to host a carrier air wing and a vast majority of the U.S. Eighth Army, respectively. While these projects were principally facility-focused, the model of cooperation between local engineering firms and U.S. government program managers could be replicated to deliver ship maintenance and even new vessels.

The Navy could establish Program Executive Office–Allied Shipbuilding (PEO-Allied) to take charge of outsourcing and provide robust quality control for vessel maintenance at advanced allied shipbuilding firms. PEO-Allied also should coordinate with allied operational commanders to ensure U.S. maintenance and shipbuilding schedules minimize impact on Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and Republic of Korea Navy vessel maintenance schedules.

PEO-Allied also could play a role in recapitalizing the combat logistics and sealift fleet. It could be a conduit for foreign shipbuilding firms to bid on construction of U.S. vessels. For example, it could announce a request for proposal for a 30-ship roll-on/roll-off (Ro/Ro) sealift recapitalization, including not only technical requirements, delivery timelines, and cost estimates, but also domestic construction requirements. Higher scores in the competitive bid process could be awarded to firms that propose a higher domestic build ratio and capital investments in smaller domestic yards. Such contracts would encourage allied shipbuilding firms to form joint ventures with domestic U.S. shipbuilders, spurring investments in these smaller domestic shipyards.

Inadequate U.S. shipbuilding infrastructure is a critical risk to Navy readiness. Strategic competitors abroad and the material state of the fleet demand the United States accelerate modernization while minimizing impacts on additional shipbuilding and maintenance. Without the domestic shipbuilding capacity to meet this overwhelming demand, it may be time to consider solutions that tap into the considerable industrial and technical expertise of U.S. Asian allies. If carefully implemented, such a plan could give the Navy a modern, well-balanced fleet, modernized domestic shipbuilding capability, and greater economic ties with military allies in the western Pacific.

1. Brent Sadler, “The USS Bonhomme Richard’s Decommissioning: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” The Heritage Foundation, 17 December 2020.

2. ADM Michael M. Gilday, USN, Navigation Plan, January 2021; and Roger Wicker, “SHIPYARD Act of 2021,” U.S. Senate, 28 April 2021.

3. Government Accountability Office, “Navy Maintenance Navy Report Did Not Fully Address Causes of Delays or Results-Oriented Elements,” report to Congressional committees (October 2020).

4. David Larter, “The U.S. Military Ran the Largest Stress Test of Its Sealift Fleet in Years. It’s in Big Trouble,” Defense News, 31 December 2019.

5. U.S. Department of Transportation Maritime Administration, “National Defense Reserve Fleet Inventory,” 31 July 2021.

6. Congressional Research Service, “Navy John Lewis Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress,” 31 August 2021.

7. Hyundai Heavy Industries, “Naval & Special Ship Business Unit Brochure.”

8. Japan Ministry of Defense, “Defense Programs and Budget of Japan Overview of FY2015 Budget,” 14 May 2015.

9. “Supporting the Royal Navy at Sea—The Tide-class Tankers,” Navy Lookout, 25 August 2018.